Good Morning POU!

This week’s topic will feature men and women who have lived the double life as undercover agents for various federal law enforcement agencies. Their lives on the line as they tread a very dangerous and complicated world as a person of color often working under threat of both alleged suspects as well as their own peers in the law enforcement arena.

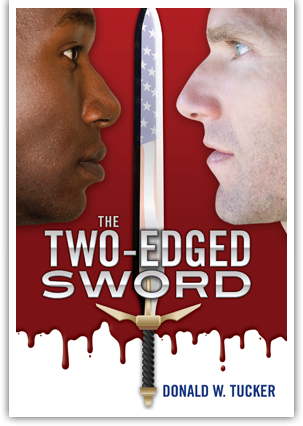

The Two-Edged Sword

Donald Tucker is the author of “The Two-Edged Sword, whose book recounts both his adventures and his experiences dealing with overt racism with federal law enforcement, as he rose from an undercover agent in narcotics to protecting Presidents.

Tucker grew up in the ghetto of Chicago’s South Side. His “one in a million” winning lottery ticket out was a football scholarship to the University of Iowa. With a bachelor’s in criminology/sociology, he became one of the first black federal drug and law enforcement agents in 1961.

Untrained and totally naïve, the rookie was sent into what can only be called dangerous and life-threatening situations throughout the seedy underbelly of the city of his birth. As he and the few other African Americans were hired as what amounted to be temporary “show us what you’ve got” positions, far less qualified whites were given permanent positions. Whites were given assignments that were far more glamorous and less dangerous that the black agents also. Tucker found himself on the streets posing as a hustler sitting in undesirable dumps attempting to score drugs while his white colleagues wore suits and ties sat in offices and “handled’ informants.

However, there were many who tried to push him back from whence he came. The Chicago native was reared “in a postage-stamp apartment that housed five children and four adults.” He got his start on a football scholarship at the University of Iowa, where he majored in sociology. He described his shock later as an Army recruit in the South in the early 1960s experiencing segregation first-hand. Then he was told by his commander not to participate with his unit in Army security for the 1963 desegregation of the University of Mississippi because the sight of a black solider might antagonize onlookers. Tucker says he threw himself into his law enforcement work. On his wedding day, he excused himself between the service and reception to build a case against a suspected counterfeiter.

“Whether posing as a drug buyer or dealer in counterfeit money, protecting a political dignitary or performing administrative duties, I always knew that for many I was ‘just a blackie,’ one step removed from the cotton fields,” he writes in his memoir. Racism was rampant despite Tucker’s high-ranking role at the federal government level. During an undercover assignment, Tucker was pulled into a police car by local police officers who didn’t know he was an undercover agent. A white police officer proceeded to unleash a racial tirade against Tucker that even threatened his death.

“Too many buy viagra kijiji times the risks were far greater than anticipated, but I was young and dumb,” writes Tucker. “I didn’t know what I was doing until I felt a .45 slammed against my head. Or, until I found myself being cuffed and dragged into a police car manned by an officer who had no way of knowing I was an undercover agent.”

“That I survived to tell my story is sheer luck.”

When he joined the U.S. Secret Service in 1965, he was one of only 19 blacks out of more than 300 agents nationwide. The black agents, he writes, never stood “shoulder to shoulder” with their white colleagues when it came to commendations and promotions.

He initially hid his anger and kept quiet for fear of losing his job. But he could not keep quiet forever.

“Around the office and in Secret Service circles I became known as Tucker, the Troublemaker,” he writes, “the agent who would stand up for any other black — or white agent, too, if need be — to fight for equal recognition and equal consideration.”

Some of Tucker’s colleagues feel The Two-Edged Sword is ill-tempered and is a shot at the very agencies that gave him an opportunity to live an abundant life. In fact, he says, a co-worker who he asked to critique his manuscript told him he sounded like “an angry black man criticizing everything.”

“Some guys in the U.S. Secret Service (USSS) were terrified when they heard I was writing a book,” he said. “But some agents enjoyed the book. The fact is I could have been much tougher on the USSS.”

Tucker’s life story has been described as “a best-selling 007 whodunit, more fiction than fact — yet all of it really happened.” It is at once chilling and inspiring.

He acted, as he put it, out of his own regard for the betterment of his colleagues and those who would surely follow him.

“I was fighting for blacks to have a better career,” he explained. “I was fighting for females and others also.”

When asked how the USSS has changed over the years, Tucker was candid as usual.

“I think the difference today is we have more people who are not willing to stand up and are not willing to put their financial security on the line. Today there are blacks pretending they had no trouble getting where they are in the service without the paths we paved for them. They believe they have gotten where they are without programs like affirmative action.”

Tucker cites a discrimination suit against the USSS that is still pending as evidence that a lot of work still needs to be done in federal law enforcement. He says some of the issues in the complaint are the same ones he encountered years ago.

Tucker’s example to the USSS, his fellow agents, and to readers of his book is best stated by the author himself.

“What good is this paycheck if we can’t be treated as equals?”