Good Morning POU!

This week we will feature African Americans that are true war heroes. These are the stories of legends. Each would make an incredible feature film and no embellishment would be required.

The Battle of Henry Johnson

Nearly a century later, the stage is now set for America to meet a long-overdue national obligation now that Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel has recommended New Yorker Henry Johnson for the Medal of Honor.

Ninety-six years ago, during World War I, Johnson almost single-handedly repelled an assault by as many as 24 German soldiers on his post in France. He fought with rifle, knife and bare fists, suffering grievous injury while saving the life of his trenchmate.

The U.S. refused to recognize Johnson’s valor. The military denied him both the Purple Heart and a disability pension, despite his loss of a shinbone and most of the bones in one foot.

All because Henry Johnson of Albany was black.

A railroad station redcap when the U.S. entered the war, Johnson became one of 2,000 African Americans who enlisted in a newly formed, all-black National Guard unit that drilled with broomsticks in Harlem because the Army had no interest in equipping the men with rifles.

At the time, most black soldiers were limited to supply roles. Johnson’s unit, which came to be known as the Harlem Hellfighters, insisted on going into combat. With white Americans refusing to serve beside black Americans, the brass placed the men under French command.

So, after midnight on May 15, 1918, Johnson was isolated at the front with Needham Roberts, a teenager from Trenton. Germans came out of the darkness, firing their weapons and throwing grenades. Johnson took hits, then came to his feet fighting.

“A rabbit would have done that”

Henry Johnson, who stood 5-foot-4 and weighed 130 pounds, had enlisted in the all-black 15th New York National Guard Regiment, which was renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment when it shipped out to France. Poorly trained, the unit mostly performed menial labor—unloading ships and digging latrines—until it was lent to the French Fourth Army, which was short on troops. The French, less preoccupied by race than were the Americans, welcomed the men known as the Harlem Hellfighters. The Hellfighters were sent to Outpost 20 on the western edge of the Argonne Forest, in France’s Champagne region, and Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, from Trenton, New Jersey, were given French helmets, French weapons and enough French words to understand commands from their superiors. The two American soldiers were posted on sentry duty on the midnight-to-four a.m. shift. Johnson thought it was “crazy” to send untrained men out at the risk of the rest of the troops, he later told a reporter, but he told the corporal he’d “tackle the job.” He and Roberts weren’t on duty long when German snipers began firing at them.

After the shots rang out, Johnson and Roberts lined up a box of grenades in their dugout to have ready if a German raiding party tried to make a move. Just after 2 a.m., Johnson heard the “snippin’ and clippin’ ” of wirecutters on the perimeter fence and told Roberts to run back to camp to let the French troops know there was trouble. Johnson then hurled a grenade toward the fence, which brought a volley of return gunfire from the Germans, as well as enemy grenades. Roberts didn’t get far before he decided to return to help Johnson fight, but he was hit with a grenade and wounded too badly in his arm and hip to do any fighting. Johnson had him lie in the trench and hand him grenades, which the Albany native threw at the Germans. But there were too many enemy soldiers, and they advanced from every direction; Johnson ran out of grenades. He took German bullets in the head and lip but fired his rifle into the darkness. He took more bullets in his side, then his hand, but kept shooting until he shoved an American cartridge clip into his French rifle and it jammed.

By now, the Germans were on top of him. Johnson swung his rifle like a club and kept them at bay until the stock of his rifle splintered; then he went down with a blow to his head. Overwhelmed, he saw that the Germans were trying to take Roberts prisoner. The only weapon Johnson had left was a bolo knife, so he climbed up from the ground and charged, hacking away at the Germans before they could get clean shot at him.

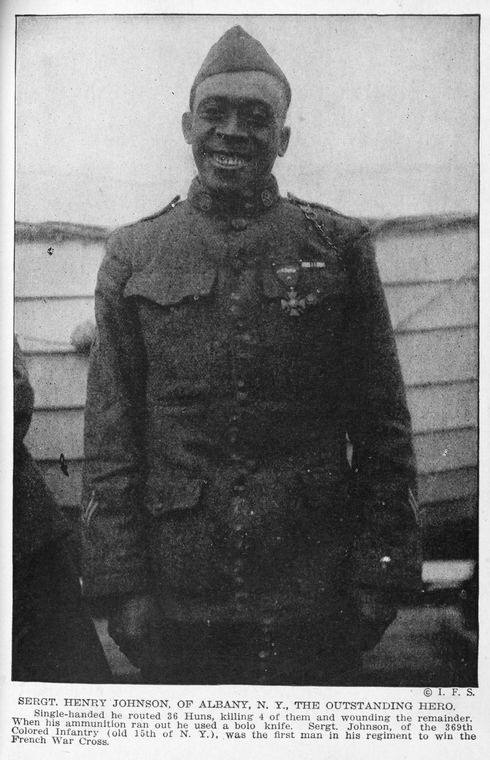

Henry Johnson in 1919, after receiving the French Croix de Guerre. Photo: New York Public Library Digital Collection

“Each slash meant something, believe me,” Johnson later said. “I wasn’t doing exercises, let me tell you.” He stabbed one German in the stomach, felled a lieutenant, and took a pistol shot to his arm before driving his knife between the ribs of a soldier who had climbed on his back. Johnson managed to drag Roberts away from the Germans, who retreated as they heard French and American forces advancing. When reinforcements arrived, Johnson passed out and was taken to a field hospital. By daylight, the carnage was evident: Johnson had killed four Germans and wounded an estimated 10 to 20 more. Even after suffering 21 wounds in hand-to-hand combat, Henry Johnson had prevented the Germans from busting through the French line.

“There wasn’t anything so fine about it,” he said later. “Just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.” In the day, the episode became known as “The Battle of Henry Johnson.”

Later the entire French force in Champagne lined up to see the two Americans receive their decorations: the Croix du Guerre, France’s highest military honor. They were the first American privates to receive it. Johnson’s medal included the coveted Gold Palm, for extraordinary valor.

Henry Johnson and the Harlem Hellfighters in a parade up Fifth Avenue upon their return to New York in February, 1919. Photo: New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs

Like hundreds of thousands of young American men, Henry Johnson returned from World War I and tried to make a life for himself in spite of what he had experienced in a strange and distant land. With dozens of bullet and shrapnel wounds, he knew he was lucky to have survived. His discharge records erroneously made no mention of his injuries, and so Johnson was denied not only a Purple Heart, but a disability allowance as well. Uneducated and in his early twenties, Henry Johnson had no expectations that he could correct the errors in his military record. He simply tried to carry on as well as a black man could in the country he had been willing to give his life for.

He made it back home to Albany, New York, and resumed his job as a Red Cap porter at the train station, but he never could overcome his injuries—his left foot had been shattered, and a metal plate held it together. Johnson’s inability to hold down a job led him to the bottle. It didn’t take long for his wife and three children to leave. He died, destitute, in 1929 at age 32. As far as anyone knew, he was buried in a pauper’s field in Albany. A man who had earned the nickname “Black Death” in combat was quickly forgotten.

The denial of a disability pension, the Purple Heart oversight, the fleeting recognition—none of it surprised his son, Herman Johnson, who later served with the famed Tuskegee Airmen. The younger Johnson knew all about Jim Crow, second-class citizenship and the systematic denial of equal rights to black Americans. But in 2001, 72 years after Henry Johnson’s death, a great and unlikely mystery was revealed to the soldier’s estranged son: On July 5, 1929, Henry Johnson had been buried not in an anonymous grave in Albany, but with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. Historians who located Johnson’s place of burial believed there could be no more appropriate honor for Herman’s father, who proved his valor on the night of May 14, 1918, in the Argonne Forest.

Defense Secretary Hagel endorsed Johnson for the nation’s highest accolade at the urging of Sen. Chuck Schumer, who has pressed the issue for 15 years and who two years ago submitted voluminous documentation of Johnson’s heroism.

That record met the Pentagon’s high standards of proof, satisfying Hagel, and before him U.S. Army Secretary John McHugh, that Johnson’s incredible exploits were, beyond all doubt, true.

In recent years, a chain-of-command endorsement in the form of a memo from Gen. John J. Pershing, commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, written just days after Johnson’s heroics in the Argonne, was discovered in an online database by an aide to Senator Charles Schumer of New York. Schumer believes that this endorsement, not known to exist for nearly a century, will be enough to bestow another posthumous award on the man known as Black Death. “There is no doubt,” Schumer said this past March, standing before a statue of Johnson in Albany, “he should receive the Medal of Honor”—the nation’s highest military honor.

Schumer must now win passage of legislation authorizing a Medal of Honor in connection with events that took place more than five years ago, the traditional time limit for the award. Washington’s gridlock must not stand in the way. Congress must authorize Obama to consider Johnson for the Medal of Honor, so the President can right a racial wrong done almost a century ago.