Good Monday Morning POU!

This week, as the NCAA proceeds to make billions off the popularity of college basketball, let’s take a look at some of the black players and coaches that propelled the game from the playgrounds to the “A billion dollars for a perfect bracket” game that it is today – Stories of HBCU legends, racism and triumph within college basketball.

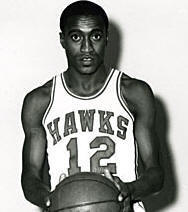

Cleo Hill

Most of the players Cleo Hill works with in the Youth Development Program at Newark Vocational High School do not know that he was a first-round NBA draft pick in 1961. They don’t know that he scored 2,488 points at Winston-Salem. They don’t know because Hill isn’t a household name. “They thought that I played, but, you know, I didn’t want to talk too much about it,” Hill said from his home in Orange, N.J. “Kids ask questions, and then it’s ‘What happened?’ and then you try to explain that situation, and that’s hard to do.”

Some say he was a victim of circumstance; some say he was a victim of a racism and a vindictive team owner.

Before MJ

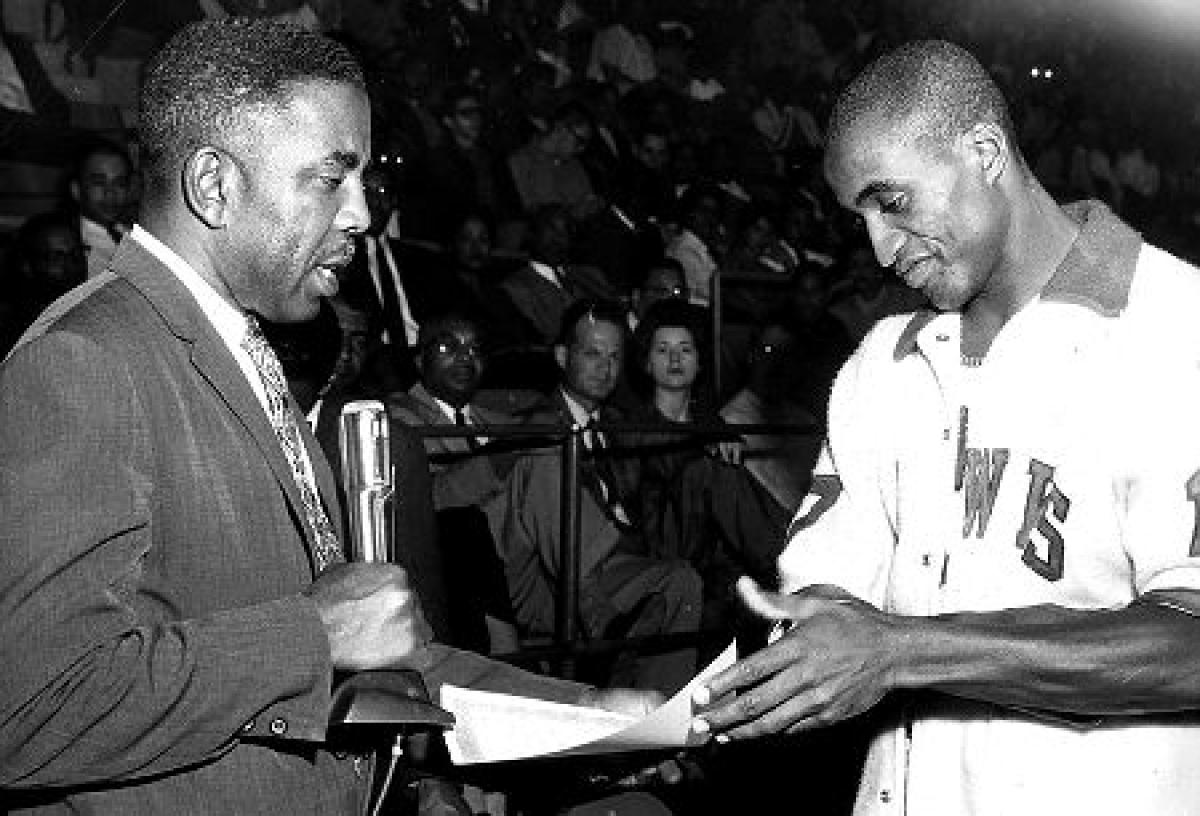

Before there was MJ, there was Cleo Hill. Many consider him one of the all-time greats whose misfortune was to be black and born 20 years too soon. He played college basketball at Winston-Salem Teachers College (now Winston-Salem State University) from 1957-1961 for legendary coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines before ACC schools like North Carolina, Duke and Wake Forest began recruiting black players. Playing at the predominantly girls school, the 6 foot 1 inch Hill averaged 27 points per game as a senior. Savvy basketball scouts considered Hill the best player in the country when he graduated from college. The St. Louis Hawks of the NBA drafted Hill with the 8th pick in the first round–the first African-American from a Historically Black College to be drafted in the first round.

At Winston-Salem, his impact was such that he was recently voted the best player in school history, even ahead of Hall of Famer Earl “the Pearl” Monroe who followed him in the late sixties and went on to star for the New York Knicks.

A little background here: Long time sports commentator Billy Packer, who played guard for nearby Wake Forest became friends with Hill in 1961. The naive Packer, a Pennsylvania native, decided one evening to cross the tracks to the poor side of town to watch a game between Winston-Salem and Tennessee State. He soon found he was the only white guy in the packed gym. Coach Gaines recognized him from a newspaper article and invited him to sit with him on the bench. It didn’t take long for Packer to realize that the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) schools played better quality basketball (more speed and athleticism) than the so-called big time schools of the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC).

Packer was later quoted as saying, “Cleo Hill was better than anybody in the ACC. There was nobody close to him. As a matter of fact, of the guys I’ve seen in this state, Cleo Hill was the forerunner of David Thompson and Michael Jordan. The whole league had guys like that. Out of that Cleo and I became buddies and we used to scrimmage against them.” This came from a man who played on two consecutive ACC champions in 1961 and 1962. Packer organized numerous informal scrimmages between Wake Forest and Winston-Salem on Sunday mornings which were probably against the law at that time in the Jim Crow South. No coaches or referees were present at the unsupervised scrimmages, but they played top quality basketball and had fun doing so. The scrimmages were played at the Winston-Salem gym. At Wake, they would have caused an incident. For example, John McClendon, the Hall of Fame coach from nearby North Carolina Central sought to attend a game at Duke but was told he couldn’t come into the arena unless he was dressed as a waiter!

Cleo Hill had all the shots–hook shots with either hand, a sweet jump shot, a two handed set shot, and spectacular athletic ability. His old playground buddy from Newark, NJ, Al Attles described Hill as the greatest high school player he had ever seen. Attles played college ball at North Carolina Central, another CIAA school and became a defensive star for the Philadelphia and Golden State Warriors. He later coached the Warriors to an NBA championship.

In his first NBA game, Hill scored 26 points. But the NBA wasn’t ready for a high-flying athlete like Hill with a 44 inch vertical leap, who could dunk from the free throw lane. His teammates on the Hawks, Bob Pettit, Clyde Lovelette and Cliff Hagan, Hall of Famers all, complained to the coach that Hill was shooting too much and wasn’t passing the ball enough to them. They quickly caught on that if Hill scored a lot of points, they wouldn’t score as many, and it would cost them money at contract time.

Coach Paul Seymour’s mission was to win basketball games, and he wanted his best players on the floor. The previous season, the Hawks had made it to the NBA Finals where they lost to the Boston Celtics led by black superstar Bill Russell. If they were ever going to beat the Celtics, they needed more firepower.

There was more to it than that. The Hawks were scheduled to play an exhibition game against the Celtics in Lexington, Kentucky, and Russell was refused service in the hotel restaurant. He approached Hill and the other black players about boycotting the game. They did so. The Boston players were publicly supported by team owner, Walter Brown and had no problem with their fans. In St. Louis, a Southern city, it was a different story. the local press skewered Hill and the other two black players, Woody Sauldsberry and Si Green, demanding fines and suspensions. Hawks owner Ben Kerner said nothing, and shortly thereafter traded Sauldsberry and Green. He ordered Coach Seymour to bench Hill and instruct him to pass the ball more.

After Hill’s first NBA game, the team’s veteran stars essentially froze Hill out, refusing to pass him the ball and refusing to rebound his shots. They felt that the rookie, Hill, should have to work his way into the starting lineup. Coach Seymour called a team meeting and threatened to fine them. Kerner had a revolt on his hands, and it was easier to fire the coach than his star players.

The color blind Coach Seymour insisted on playing the rookie, Hill, who he felt was his best player. For foolishly trying to win rather than promote racial harmony, the coach got himself fired. The new coach, Harry Gallatin drastically reduced Hill’s playing time and his scoring average dropped from double figures to 5 points per game as he spent more and more time on the pines.

The following season, 1962, Hill wasn’t the same player. His intensity was gone, and the Hawks released him in the pre-season. In those days, players didn’t have agents who could call upon the other teams seeking a place for their client. Although it was never proven, it appeared that the word was out that Hill was a trouble maker. Hill’s former coach Seymour actually did contact several teams on Hill’s behalf, but no team wanted him. “White-balled” was the word they used, according to Seymour.

Hill insists the issue had more to do with points then prejudice, but Kenny Benton, his college roommate, thinks otherwise.

“He doesn’t like to talk about it, but Cleo Hill got blackballed in the NBA,” Benton said. “He never got a chance to project his skills – he had to watch guys who couldn’t hold his jock become stars.”

Fortunately for Hill, he had earned a teaching degree and became a substitute teacher and went into coaching. He played in the Eastern League on weekends and made more money than he had as an NBA rookie. He became a successful basketball coach at Essex County College in Newark, NJ, winning 489 games in his 24 year career. He insists that he’s no longer bitter about the St. Louis incident. “It wasn’t racial, it was points,” he said. He went on to say, “the one consolation I have is knowing that if I was merely mediocre, I would have been left alone. So I guess I must have been pretty good.”

(from The Black Magic Documentary and The Ken Suskin Report)

Filmmaker Dan Klores links the rise of the United States civil rights movement to the history of African American basketball players and coaches at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Narrated by actor Samuel L. Jackson and musician Wynton Marsalis, this documentary explores the intersection of sports and culture through game footage and interviews with former players and coaches. Each day we will provide segments of the documentary: