Good Morning POU!

This week’s topic is one that I’ve often wondered about but never really got into the history. Last week’s topic led me to reading more on this subject. Capitalism is far from perfect, but what would is more appealing about communism or socialism or even marxism when it comes to prominent African American writers and artists? Many writers from the Harlem Renaissance to the Black Arts Movement were advocates of those political and economic systems and it couldn’t have just been a coincidence, could it? We’ll see where the research takes us!

When the Communist Party USA was founded in the United States, it had almost no black members. The Communist Party had attracted most of its members from European immigrants and the various foreign language federations formerly associated with the Socialist Party of America; those workers, many of whom were not fluent English-speakers, often had little contact with black Americans or competed with them for jobs and housing.

The Socialist Party had not attracted many African-American members during the years before the split when the Communist Party was founded. While its most prominent leaders, including Eugene V. Debs, were committed opponents of racial segregation, many in the Socialist Party were often lukewarm on the issue of racism. They considered discrimination against black workers to be an extreme form of capitalist worker exploitation. In addition, the party’s allegiance with unions that discriminated against minority workers compromised its willingness to attack racism directly; it did not seek out African-American members, nor did it hold recruitment drives where they lived. Some African Americans disaffected by Socialist attitudes joined the Communist Party; others went to the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), whose political philosophy was essentially Marxist in nature.

The Communist Party at first repeated the economic position of the Socialist Party. Committed from the outset to bringing about world revolution, the party sympathized with anti-colonial and “national liberation” movements around the globe. Its view of the black worker struggle and on civil rights for blacks were based in the broader terms of anti-colonialism. From its early years in the U.S., the party recruited African-American members, with mixed results.

In its early days, the party had the greatest appeal among black workers with an internationalist bent. From 1920 it began to intensively recruit African Americans as members. The most prominent black Communist Party members at this time were largely immigrants from the West Indies, who viewed a black worker struggle as being part of the broader campaigns against capitalism and imperalism.

At the 1922 Fourth Congress of the Comintern (Communist International), Claude McKay, a Jamaican poet, and Otto Huiswoud, born in Suriname, persuaded the Comintern to set up a multinational Negro Commission that sought to unite all movements of blacks fighting colonialism. Harry Haywood, an American communist drawn out of the ranks of the African Blood Brotherhood, a socialist group with a large number of Jamaican émigrés in its leadership, also played a leading role. McKay persuaded the founders of the Brotherhood to affiliate with the Communist Party in the early 1920s. The African Blood Brotherhood claimed to have almost 3,500 members; relatively few of them, however, joined the party.

The Comintern directed the American party in 1924 to redouble its efforts to organize African Americans. The party complied by creating the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC) in 1925. That organization was also a failure: the black press denounced it and the labor movement generally ignored it, aside from a few party-controlled unions that had few black members.

The ANLC, for its part, became isolated from other leading black organizations. It attacked the NAACP and related organizations as “middle-class accommodationists” controlled by white philanthropists. The ANLC and the Party had a more complex relationship with Marcus Garvey‘s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA); while the party approved of Garvey’s fostering of “race consciousness”, it was strongly opposed to his support for a separate black nation. When the party made efforts to recruit members from the UNIA, Garvey expelled the party members and sympathizers in its ranks.

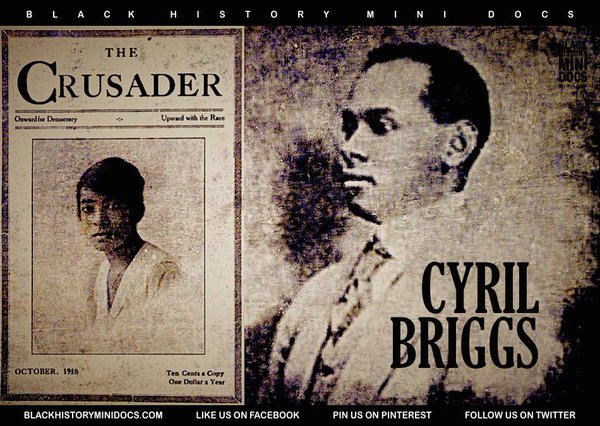

Cyril Briggs and The African Blood Brotherhood

Cyril Valentine Briggs was born on May 28, 1888 on the Caribbean island of Nevis, part of the West Indies. His father, Louis E. Briggs, was a white plantation overseer; his mother, Mary M. Huggins, was of Afro-Caribbean ethnicity (I think we all know what that means).

Little is known about Briggs’ first 7 years in America, as he never wrote of the experience in his extremely short autobiographical note housed in the Marcus Garvey Papers at UCLA “Angry Blond Negro.”

Briggs’ first American writing job came in 1912 at the Amsterdam News.

In 1917, Briggs founded the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), one of the seminal groups of African-American associations. His goal was to stop lynching and racial discrimination, and ensure voting and civil rights for African Americans in the South. He also called for black self-determination. The group initially opposed American involvement in the First World War.

In 1918, the ABB started a magazine called The Crusader, which supported the Socialist Party of America‘s platform and helped expose lynchings in the South and discrimination in the North. Briggs hoped that President Woodrow Wilson would support voting rights for African Americans in the South after the service of veterans in the war. Southern Democratic congressmen opposed any changes.

In February 1919, Briggs began to change his ideas, and his new thinking was expressed in articles in the Crusader. He began to draw parallels between the plight of black workers in the United States and impoverished working class whites, who were mostly recent immigrants or their descendants from Europe. Over ensuing months, Briggs began to consider the system of capitalism as the villain, and he argued in favor of a common cause and common action by workers of all races.

The Crusader eventually reached a total readership of 36,000 persons, mostly in Harlem.

Disillusioned by Socialist and progressive efforts, Briggs joined the Communist Party USA in 1921, his leadership of the ABB gained Marxist influences. He called for control by African-American workers of the means of production which employed them, whether in industry or in agriculture.

Briggs became a leading exponent of racial separatism. Briggs saw American White-Black racism as a form of “hatred of the unlike” that draws “its virulence from the firm conviction in the white man’s mind of the inequality of races—the belief that there are superior and inferior races and that the former are marked with a white skin and the latter with dark skin and that only the former are capable and virtuous and therefore alone fit to vote, rule and inherit the earth.” Briggs reminded his readers that racial antipathy is a two-way street and that “the Negro dislikes the white man almost as much as the latter dislikes the Negro.”

Briggs proposed a “new solution” then emerging, in which the African American had come to the realization that “the salvation of his race and an honorable solution of the American Race Problem call for action and decision in preference to the twaddling, dreaming, and indecision of ‘leaders.’” Instead, “nothing more or less than independent, separate existence” was called for — “Government of the (Negro) people, for the (Negro) people and by the (Negro) people.”

Briggs’s Marxist views as applied to a separatist government caused a rift with Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). While opposed to Garvey’s nationalist movement, the Marxists of the ABB did not view “Africa for the Africans” as an invitation to capitalist development. Briggs wrote, “Socialism and Communism [were] in practical application in Africa for centuries before they were even advanced as theories in the European world.”

The ABB attempted to organize from inside the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and advocated a policy of critical support for its leader, Marcus Garvey. ABB leaders Briggs and Claude McKay participated in the UNIA’s 1920 and 1921 international conferences in New York. At the second conference, McKay arranged for Rose Pastor Stokes, a white leader of the Communist Party, to address the assembly.

The ABB became highly critical of Garvey following the apparent failure of the Black Star Line and Garvey’s July 1921 Atlanta meeting with Grand Kleagle Clarke of the Ku Klux Klan. In June 1922, The Crusader announced that it had become the official organ of the African Blood Brotherhood. Arguing that the UNIA was doomed unless it developed new leadership, the magazine sought to convert the UNIA’s membership to the ABB. In return, Garvey called for his followers to disrupt meetings of these oppositional groups.

In addition to the dispute with Garvey, Briggs and the ABB were targeted for investigation by police and federal law enforcement agencies. Historian Theodore Kornweibel reports that the government began manipulating radical organizations in conjunction with legal prosecution under the pretence of disrupting opposition to World War I. Following the end of the war, a government campaign against communists, anarchists, and other radicals was instituted at the direction of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer (himself the victim of two anarchist bomb attacks) in what came to be called the First Red Scare. Government agents were secretly planted in the UNI and the ABB. These agents provided intelligence to the FBI while in some case sabotaging meetings, and acting as agents provocateurs.

The Crusader ceased publication in February 1922, following Garvey’s indictment for mail fraud. Briggs continued to operate the Crusader News Service, providing news material to affiliated publications of the American black press. As cooperation with the Communist Party increased, the ABB ceased to recruit separately.