This week we will look at athletes that took part in political and social protests. We will revisit posts from the week of April 28, 2014, as well as add new posts including today’s entry.

African American players at Syracuse University boycotted the 1970 football season in a collective effort to demand change and promote racial equality within the University football program. These student-athletes wanted better medical care for injured players and stronger academic support for African American student-athletes; the right to compete fairly for any position on the starting team; and racial integration of the football coaching staff.

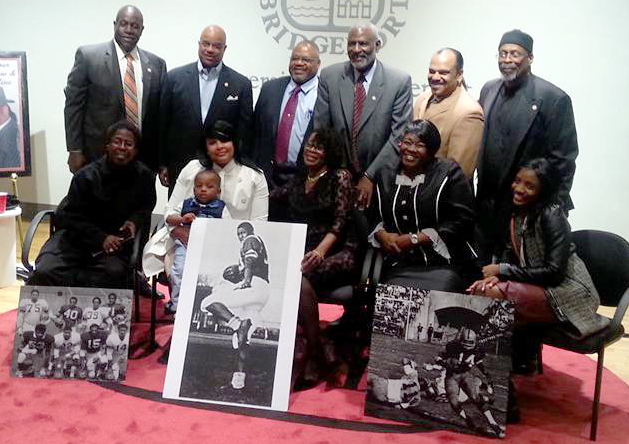

Although called the “Syracuse 8” by the media in 1970, the group included nine individuals. They are Gregory Allen ’72, Richard Bulls ’73, John Godbolt ’73, Dana Harrell ’71, G73, John Lobon 9’73, Clarence “Bucky” McGill ’72, A. Alif Muhammad ’71, Duane Walker ’80 and Ron Womack ’71.

The activism actually began in the spring of 1969 with the black players accusing (then) Coach Floyd “Ben” Schwartzwalder of discriminatory practices. The ensuing season began with a home game against Kansas and the most potent riot in Syracuse campus history. A pre-game confrontation between nearly 100 policemen and at least 400 students featured flying rocks, bottles, and wood, pepper gas, and nightstick beatings.

Later that school year SU Chancellor John E. Corbally Jr. convened a commission to investigate and assess the situation. The commission’s 60-page report concluded that the players’ response to the racial injustices of the time, and their efforts to bring about change, were justified.

In 2006, at halftime of the SU-Louisville game, the group was recognized and presented with their SU Letterman’s jackets, which they never received after leaving the team 36 years ago. These men sacrificed playing the sport they loved and a possible career after college to stimulate social change and needed awareness.

New York Times article from 2006

In May 1970, nine African-American football players at Syracuse University boycotted spring practice to protest what they viewed as racial discrimination and insensitivity in the program headed by its longtime coach, Ben Schwartzwalder.

The players — Greg Allen, Richard Bulls, John Godbolt, Dana Harrell, John Lobon, Alif Muhammad, Clarence McGill, Duane Walker and Ron Womack — were known at the time as the Syracuse Eight. (The news media were unaware that an injured athlete was also involved in the boycott.)

Thirty-six years later, the university formally welcomed the nine players back into the fold. During an emotional two-day tribute Friday and yesterday attended by eight of the players, they were recognized by the university’s chancellor, Nancy Cantor, for an act of courage in standing up for what they believed. At a public ceremony Friday evening, the nine received a formal apology from the university and the Chancellor’s Medal. At halftime of the Orange’s 28-13 loss to sixth-ranked Louisville yesterday, they received their letterman’s jackets.

John Lobon was a junior defensive lineman in 1970. Lobon, the senior vice president and loan officer for the Connecticut Development Authority, missed the 1970 season. He returned for his senior year but said he felt alienated and estranged from the team and the university. Lobon graduated but said he never felt he was part of the university until this year.

“Yesterday was the beginning of a new day,” he said in a telephone interview yesterday. “I forgave Syracuse University long ago. I felt like an outsider, but I was committed to the idea that you’re going to have to respect and remember who I am, because I’m never going to let that go and I’m never going to let you let it go.”

He added: “I left my heart here, but I had to take my soul. Now I’ve returned and you’ve given me back my heart, and now I feel I can let you be a part of my soul.”

The ceremony Friday was capped by an emotional speech from Jim Brown, the former Syracuse all-American who went on to a legendary professional football career. It was Brown who, in 1970, spoke to the nine Syracuse players and tried to act as peacemaker between them and Schwartzwalder, who coached Brown in the 1950’s.

“I was there trying to work it out,” Brown said yesterday in a telephone interview. “I was there to help resolve it. I listened to them and they made all the sense in the world, so I went to Ben and tried to represent the fact that these youngsters were making sense and he should take into consideration what they were doing.

“Ben had no clue, he had no understanding of what they were doing. He told them they were football players; they weren’t black and all that other stuff, they were football players. He didn’t budge.”

On Friday, Brown was overcome as he looked at the former players, who are now in their mid-50’s. “I saw eight black men, well dressed, successful, with a lot of dignity, a lot of humanity, a lot of understanding, sitting together having stayed together on a principle,” he said. “Here they were sitting in front of me, 36 years later. It was an unbelievable experience. It was one of the greatest nights I have been involved in.”

Cantor said that as she reviewed a report the university made at the time of the boycott, as well as news coverage of the Syracuse Eight, she realized that Schwartzwalder’s attitude reflected a university-wide intransigence.

She said the problems of the Syracuse Eight in 1970 reflect the still-vexing issue of diversity in 2006, “as we all in universities think about the role that we can play in creating diverse and inclusive environments that really come true to the pledge that all talent can flourish, that we really are supposed to be places where all talent feels that it can flourish in a fair and just way, in a welcomed way.”

She added: “At the core of what happened was that their willingness to stand up and speak about what had been long and daily slights were met with an unresponsive, some might say deaf, institutional ear.” She emphasized that she was “not pointing fingers and saying, ‘They were bad and we’re great,’ ” referring to the differences between her administration and the Syracuse administration at the time. “At the core of so much inner-group distress of chilly climates, hostile climate, of the inability of places to be places for talent to flourish, is really, How willing are you to listen?”

The academy makes its share of mistakes, and its ill-defined relationship with intercollegiate athletics is one of the greatest. Having said that, universities get it right more often than they get it wrong.

This weekend, in Syracuse, one university got it right.