OK, you may be like me and didn’t really know what Industrial Design entailed…(or probably you do and I just be not knowing!)

This week we’ll feature furniture designers, appliance designers, typographers, graphic design…who knew? Did you ever wonder who designed your hair dryer? or toaster? how about your trash can?

“Practically every product in the Sears, Roebuck line I had a hand in at one time or another.”

Charles Harrison first tried to join the design team at Sears, Roebuck and Company in Chicago in 1956. A manager told him that there was an unwritten policy against employing black people. Sears eventually hired him in 1961, and he worked there for 32 years, becoming chief designer and developing more than 600 products, many of them best sellers.

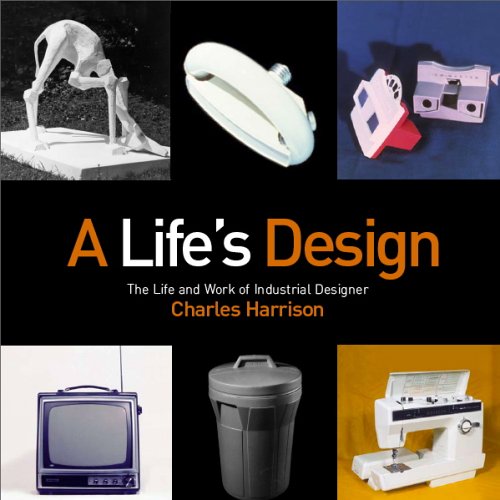

In 1966, Charles got rid of an everyday nuisance—the early-morning clanging of metal garbage cans—by creating the first-ever plastic garbage bin. “When that can hit the market, it did so with the biggest bang you never heard,” wrote Harrison in his 2005 book, A Life’s Design. “Everyone was using it, but few people paid close attention to it.”

And so it was for some 600 other household products that Harrison designed over his 32 years at Sears—everything from blenders to baby cribs, hair dryers to hedge clippers. Consumers snatched his wares from store shelves and ordered them from Sears’ catalog. And yet few stopped to consider their maker, who at times sketched one or two product ideas an hour at his drafting table.

He created designs for the hair dryer, riding lawn mower and see-through measuring cup. He worked on a universe of Craftsman power tools, as well as percolators, fondue pots, toasters and stoves. He dreamed up eight to 12 sewing machines every year for 12 years.

No design is more iconic than the View-Master, the 3-D viewer that Harrison helped update in the 1950s. (Only recently, with the sale of the patent to Fisher-Price, was Harrison’s form altered.)

Charles Harrison, who created a more affordable View-Master and the first plastic trash can, designed 8 to 12 Sears sewing machines ever year for 12 years. (Joeffrey Trimmingham / Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum)

Harrison tells his story in a memoir, “A Life’s Design: The Life and Work of Industrial Designer Charles Harrison.” He was born in Shreveport, La., in 1931. One of his first attempts at design as a child involved a “skate box,” the forerunner of the skateboard, which he made from an old piece of two-by-four and some skate wheels.

His father, Charles Alfred Harrison Sr., taught industrial arts first at Southern University in Shreveport, then at Texas A&M, and finally at a high school in Phoenix. The younger Harrison showed a special talent for art at City College of San Francisco. After wangling a scholarship to the Art Institute of Chicago, he earned a degree in industrial design.

He says his talent was acknowledged, but getting a design job in the ’50s was tough buy viagra lithuania because of racial prejudice. A mentor from the Art Institute, the Viennese-born designer Henry Glass, took him on and provided the experience that would allow Harrison to succeed.

Harrison’s consumers were both housewives who wanted something more sophisticated than their mothers’ inelegant, Depression-era eggbeaters, and their husbands, who took pride in their riding lawn mowers. They valued aesthetics, and so did Harrison, as long as they didn’t take precedence over function. “If you look at his products, there’s really nothing superfluous about them,” says Bob Johnson, a former vice president at Sears.

Harrison’s objective to make things fit in rather than stand out mirrored his own efforts as an African-American forging a career in the industrial design field. Sears turned him down in 1956; he says a manager told him that there was an unwritten policy against hiring black people. But he found freelance work at Sears and work at a few furniture and electronics firms. (He redesigned the popular View-Master at one job.) In 1961, Sears reconsidered and Harrison joined its 20-person product design and testing laboratory. He eventually rose to become the company’s first black executive.

Harrison traveled the world as a designer. The objects he developed — cutting-edge steam irons, electric frying pans, mixers, juicers, televisions — defined the burgeoning consumer class.

“I tried to make things appear as if they just belong. . . . They didn’t need to scream,” he says in the book. “My best efforts resulted in products that did their job as expected — you look at it, right away guess what it is supposed to do, and that’s exactly what it does.”

He was the last industrial designer to leave Sears, in 1993, when Sears did away with its in-house design team. Harrison, 77, now teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Columbia College Chicago. He is lenient when it comes to making his students consider what their designs might cost. “That can spoil a good piece of pie,” he says. But he draws a hard line when it comes to quality. After all, he says, “What designers do will affect so many people.”

Giving credit where credit is due, the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum honored Harrison with its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008. In 2007, his work was featured alongside other African-American product designers at the Designs for Life: Black Creativity 2007 exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry.

In 2006, Harrison received a Lifetime Achievement Award from FocusOnDesign, a Washington, D.C.-based group that promotes diversity in design. In the same year, he also received “personal recognition” from The Industrial Designers Society of America.

In 2000, Harrison’s work was featured in an exhibit titled “The World of a Product Designer: Charles Harrison” at the Carver Museum and Cultural Center.