Good Morning POU!

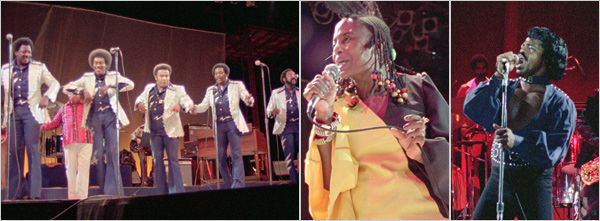

James Brown, BB King, Bill Withers, The Spinners, Miriam Makeba, Celia Cruz…all in one concert. AMAZING!

Zaire 74 was a three day live music festival that took place on September 22 to 24, 1974 at the 20th of May Stadium in Kinashasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

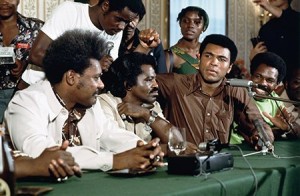

The concert, conceived by South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela and record producer Stewart Levine, was meant to be a major promotional event for the heavyweight boxing championship match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, known as The Rumble in the Jungle. When an injury forced Foreman to postpone the fight by six weeks, the festival’s intended audience of international tourists was all but eliminated and Levine had to decide whether or not to cancel the event. The decision was made to move forward, and 80,000 people attended.

In addition to promoting the Ali-Foreman fight, the Zaire 74 event was intended to present and promote racial and cultural solidarity between African American and African people. Thirty one performing groups, 17 from Zaire and 14 from overseas, performed. Featured performers included top R&B and soul artists from the United States such as James Brown, Bill Withers, B.B. King and The Spinners as well as prominent African performers such as Miriam Makeba, TPOK Jazz and Tabu Ley Rochereau. Other performers included Celia Cruz and the Fania All-Stars.

In 2009, the documentary “Soul Power” was released in 2009. The film was directed by Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, who served as the editor on the 1996 documentary When We Were Kings.

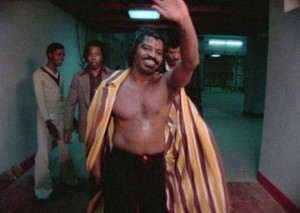

“Soul Power” presents that festival from its precarious beginnings to the finale of a shirtless, sweating James Brown singing to an African audience, “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.”

The festival was a striking sociocultural moment. African-American and Latin musicians were being introduced to Africa and African musicians amid Mr. Ali’s black-power politics and a hodgepodge of visiting music, sports and literary figures. “There was a lot of deeper meaning about why people went there and what it evoked for them,” Mr. Levy-Hinte said.

Brown and other headliners, performed at their peak, flaunting bright-colored, sharp-collared, bell-bottomed 1970s outfits that are a fashion show themselves. Americans shared the lineup with African musicians in musical solidarity.

“Soul Power,” plunges into the festival offstage and on, incorporating equipment wrangles and dressing-room encounters — like Sister Sledge teaching African girls how to dance the Bump, direct from Philadelphia — along with Brown showing off his quick footwork and splits. It is vérité with minimal explanation and a whirl of sun-drenched color and rhythm.

Zaire ’74 almost didn’t happen. The festival was “a fool’s mission” from the start, said Stewart Levine, who produced it with the South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela. (They had been roommates in the 1960s at the Manhattan School of Music; Mr. Levine produced 15 albums for Mr. Masekela, including his hit single “Grazing in the Grass.”) When Mr. Levine heard about the boxing match in Zaire, he said by telephone from Los Angeles, “it just hit me — how about a music festival?”

He said, “I had a desire to hip the general audience to what wasn’t yet called world music. And I had this cockamamie idea about the festival, and everybody said yeah.”

Not everybody. The government of Zaire subsidized the boxing match; Zaire’s dictator,Mobutu Sese Seko, wanted to burnish his country’s image. But Zaire would not finance the festival. So Mr. Levine rounded up backing from bankers in Liberia — their disgruntled representative is a character in “Soul Power” — and preparations began.

Then an injury forced Mr. Foreman to postpone the fight, separating the festival from the bout by six weeks and virtually eliminating the potential audience of international tourists. Mr. Levine had to decide overnight whether to cancel the festival.

But the performers had already been paid half their fees up front, and construction was under way. With contacts at ABC, Mr. Levine said, he prevailed on the sportscaster Howard Cosell to hold back for 24 hours the news that the fight had been postponed, lest the American musicians stay home. He was also lucky, he said, that it was Rosh Hashanah, and many of the performers’ managers were observing the holiday.

Then, as the charter flight was being loaded, James Brown arrived with 40,000 pounds of additional equipment — he had booked more shows in Africa — and refused to board unless it was on the flight with him, Mr. Levine said. The extra gear was somehow stuffed onto the plane. After a refueling stop, Mr. Levine said, “we touched the trees in Madrid on the runway. That’s how severely overweight the plane was.”

The production crew learned belatedly that Zaire’s electricity ran at 220 volts, not the 110 of their American equipment. Luckily, they discovered 110-volt generators that had been donated to Zaire by the United States Agency for International Development (and were little used due to the voltage disparity). The festival was on, more or less as planned; 80,000 people filled the stadium.

“It was interesting to watch the reaction of the mostly African audience,” said Mr. Withers, who in the film holds the crowd rapt singing “Hope She’ll Be Happier,” alone on acoustic guitar. “It’s like standing on the other side of the street watching your girlfriend walk down it and seeing how other people react to her.” The percussive, polyrhythmic salsa of Celia Cruz and the Fania All-Stars was the audience favorite, he said. And no wonder: Afro-Cuban rumba from a previous generation had strongly influenced the current Zairean pop, soukous. The film catches the conga player Ray Barretto in an impromptu jam session with African drummers.

The camaraderie between the artists during the mid-air jam session is one of the most striking sequences of Soul Power. Levine says it is inconceivable that something similar could ever take place again.

“These days you have these absurd egos from guys who just stand on a stage and rap,” he says. “But these were real artists and the camaraderie is absolutely true. What you see in the film is how it was.”

The energy seen in the journey to Africa extended into the concert performances. According to Levine, the exotic setting inspired performers to reach heights they would rarely occupy again.

“I would say that James Brown never performed any better,” he said. “Artists have good nights and they have great nights.

“And there was James Brown in the middle of the Congo at 1 am. It’s a bit different from playing Cleveland. This concert had a drama to it that led to great performances from everybody.”