GOOD MONDAY MORNING, P.O.U.!

(Originally posted in June 2015)

In this week’s series, we’ll take a look at the Policy Game (aka The Numbers Racket) and the Black men and woman who dominated this multi-million dollar industry of yesteryear.

But first, a brief overview of the game of Policy:

Gambling can be risky policy, no matter the name

Dawn Turner Trice – May 10, 2004

Before the lottery, before riverboat gambling and before casinos as we know them, there was a game called policy that ruled Chicago’s South Side in the Bronzeville neighborhood.

What was policy? I’ll put it this way: Thirty years ago when commercials began appearing on television publicizing the brand new Illinois Lottery game, some older African-Americans sitting around watching their screens sucked their teeth and said, “Child, that ain’t nothing new, that’s policy.”

According to Chicago native Nathan Thompson, author of “Kings: The True Story of Chicago’s Policy Kings and Numbers Racketeers,” policy was conceived around the late 1880s and was owned and operated for decades by black men called policy kings.

Policy players, lured by the possibility of hitting it big on a small bet, would pick a number combination, say 3-1-2, called a gig. A nickel wager could win you $5.

In the early days, winning numbers were pulled from the derby of Sam Young, policy’s creator, as he stood on the corner of State and Madison Streets. Soon, Young moved his hustle south along State Street to a saloon.

By 1915, players could learn the winning numbers by visiting the family grocery store of a couple of Italian brothers who hooked up with Young, said Thompson.

By then, Young was pulling numbers from a cardboard box, and policy regulars would gather around that box, watching the results as if they were peering into a crystal ball that held their future.

Indeed, policy was responsible for its share of crime and lawlessness as the racket grew and more policy kings were getting in on the game and battling for turf. Black ministers deeply opposed policy, preaching against it from their pulpits. Still, the city didn’t make much of an effort to get rid of it in the beginning.

“The city’s opinion was that it was a little hustle in the black community,” said Thompson. “That made it grow because nobody was paying attention. It was generating a lot of revenue throughout the Depression in Bronzeville.”

Policy, in its heyday from about the 1920s to the 1950s, did some good for the winners. It put food on the tables of struggling families. Children were sent to college on policy money. It also provided jobs.

Thompson says proceeds from policy at times helped bankroll the Negro Baseball League and even the boxing career of Joe Louis.

But the house is always set up so there are more losers than winners, and gangsters vied for their share of the cut.

“A faction of Al Capone’s Mafia went after the black guys on the South Side making all this money,” said Thompson. “And that led to the killing of one of the big policy kings.”

The other black kings decided to pull together, but that couldn’t sustain them. By 1952, policy had been put on trial, more policy kings had been murdered or jailed and the white mob had moved in, said Thompson.

“That was the end of policy [as a black establishment] and the beginning of white-controlled policy,” he said. “To say the Mafia was controlling the money meant they were also controlling the vote and the neighborhood where the money was derived.”

(SOURCE: The Chicago Tribune)

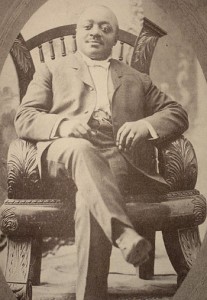

JOHN “MUSHMOUTH” JOHNSON

(From The Chicago Crime Scenes Project)

John V. “Mushmouth” Johnson was one of Chicago’s greatest gambling tycoons during the 1890s and 1900s. The newspapers (using the racially-insensitive vernacular of the day) called him variously “King of the Levee”, “The Richest Negro in Chicago”, and “King Coon of State Street”. Regardless of what you called him, for a span of twenty years, if you gambled in Chicago, you likely paid Mushmouth, at least indirectly.

Johnson was born in St. Louis to a woman who had been a nurse for Mary Todd Lincoln, but came to Chicago in the 1870s, while in his 30s, and found work as a waiter in the restaurant inside the Palmer House hotel. In 1882, he got his first taste of vice as a employee in one of Andy Scott’s gambling houses on Gamblers’ Row. Mushmouth displayed a hard-headed willingness to enforce the rules physically when gamblers who lost money demanded it back or tried to take it back by force (Johnson himself never gambled). He could also cuss a blue streak, which earned him his nickname.