Good Morning POU!

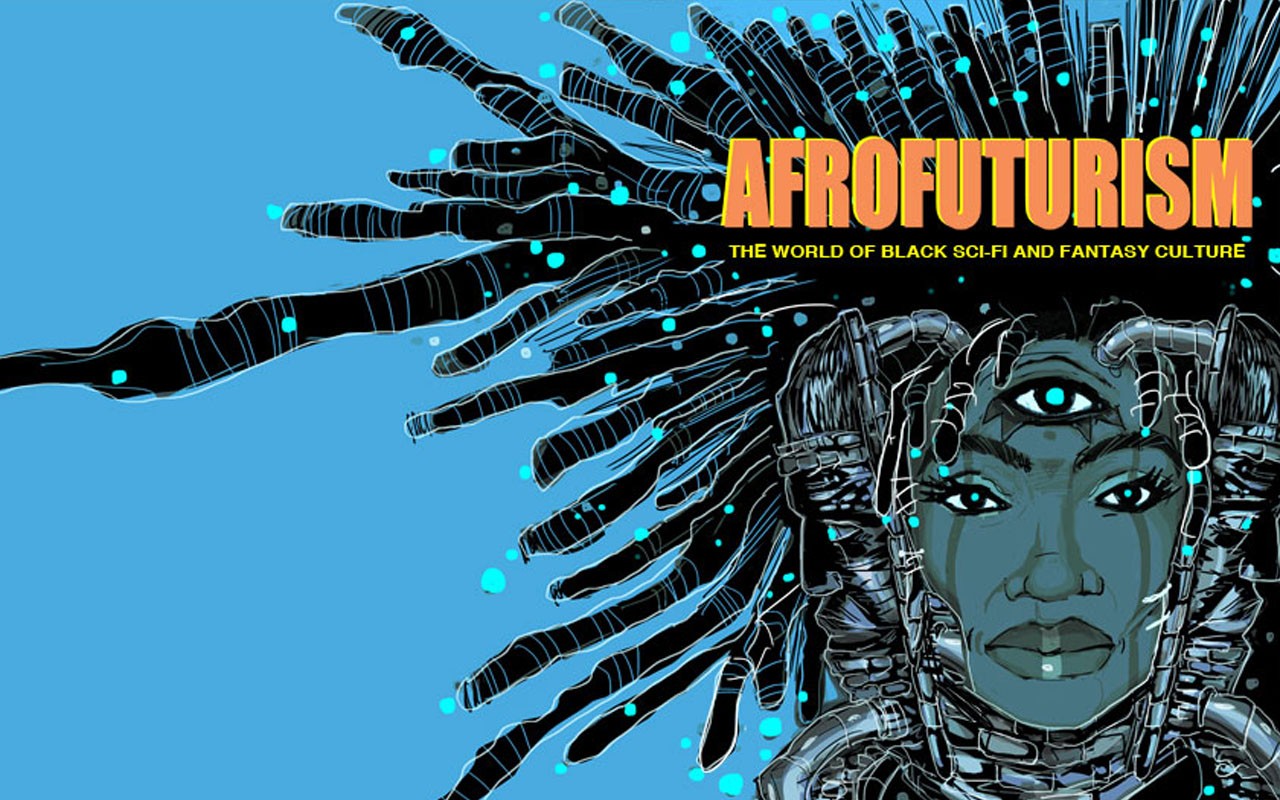

This week we’re gonna take an intergalactic trip into the world of Afrofuturism!

Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science, and philosophy of history that combines elements of science fiction, historical fiction, fantasy, Afrocentrism and magic realism with non-Western cosmologies in order to critique not only the present-day dilemmas of black people, but also to revise, interrogate, and re-examine the historical events of the past. First coined by Mark Dery in 1993, and explored in the late 1990s through conversations led by scholar Alondra Nelson, Afrofuturism addresses themes and concerns of the African diaspora through a technoculture and science fiction lens, encompassing a range of media and artists with a shared interest in envisioning black futures that stem from Afrodiasporic experiences. Seminal Afrofuturistic works include the novels of Samuel R. Delany and Octavia Butler; the canvases of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Angelbert Metoyer, and the photography of Renée Cox; the explicitly extraterrestrial mythoi of Parliament-Funkadelic, the Jonzun Crew and Sun Ra; and the Marvel Comics character Black Panther.

Beginnings

Social critic and writer Mark Dery, who is white, coined the term “Afrofuturism” in his 1994 essay “Black to the Future,” where he wondered why few African American writers embraced science fiction to tell their stories.

This is especially perplexing in light of the fact that African Americans, in a very real sense, are the descendants of alien abductees; they inhabit a sci-fi nightmare in what unseen but no less impassable force fields of intolerance frustrate their movements; official histories undo what what been done; and technology is too often brought to bear on black bodies (branding, forced sterilization, the Tuskegee experiment, and tasers come readily to mind).

Dery’s essay sparked a wave of interest among cultural scholars, notably Columbia University sociologist Alondra Nelson, who had written scholarly papers on the intersection of technology, race and who created a listserv with a following among black sci-fi aficionados.

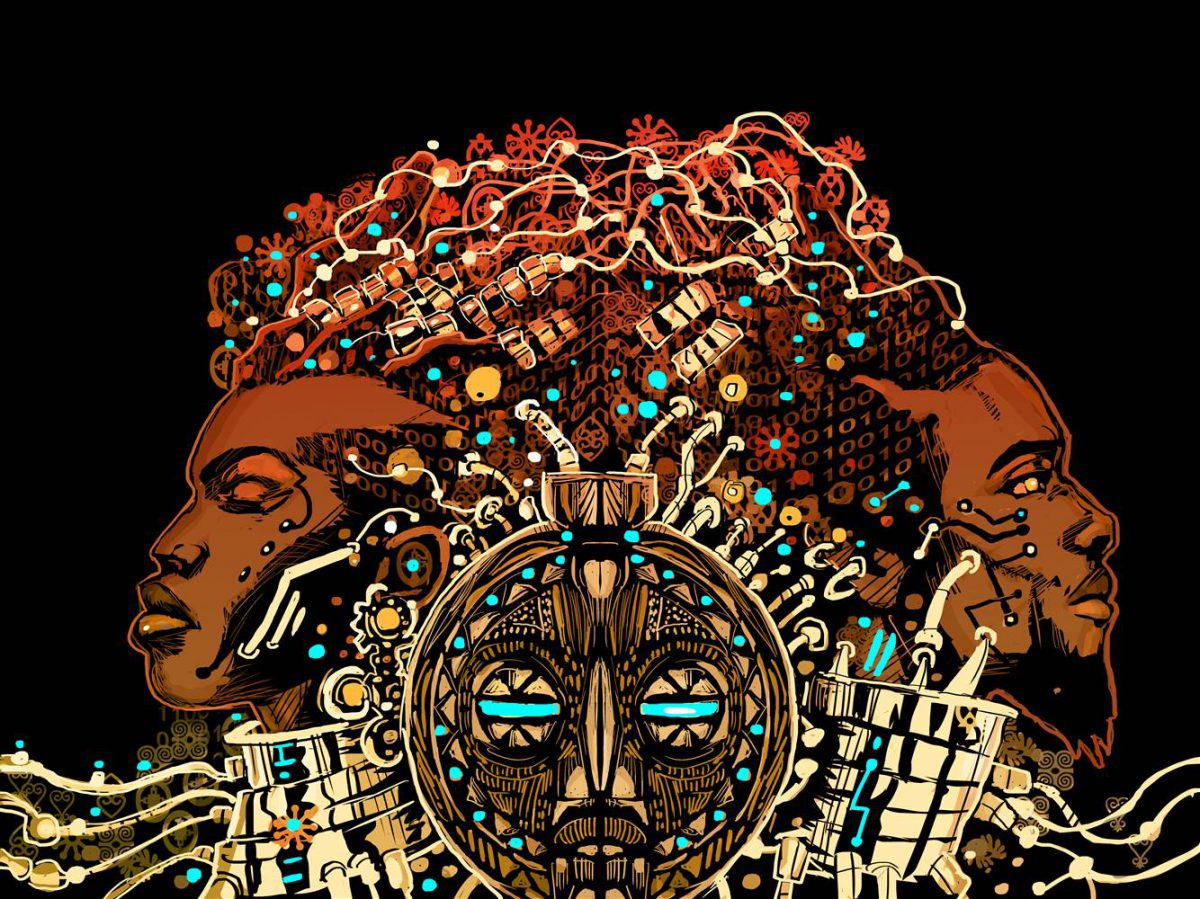

Black people have long been interested in and speculated on the future. African and West Indian writers, artists, and musicians have ancient histories of blending spiritual and mystic qualities as inspiration and reflection of the ordinary, daily life of the people around them. In the U.S., some Afrofuturists point to the avant-garde jazz composer and musician Sun Ra, who adopted a stage persona of regal, time-and-space traveling angel, an early example of the genre.

OPENING SEQUENCE FROM SUN RA’S SCIENCE FICTION FILM “SPACE IS THE PLACE” RELEASED IN 1974.

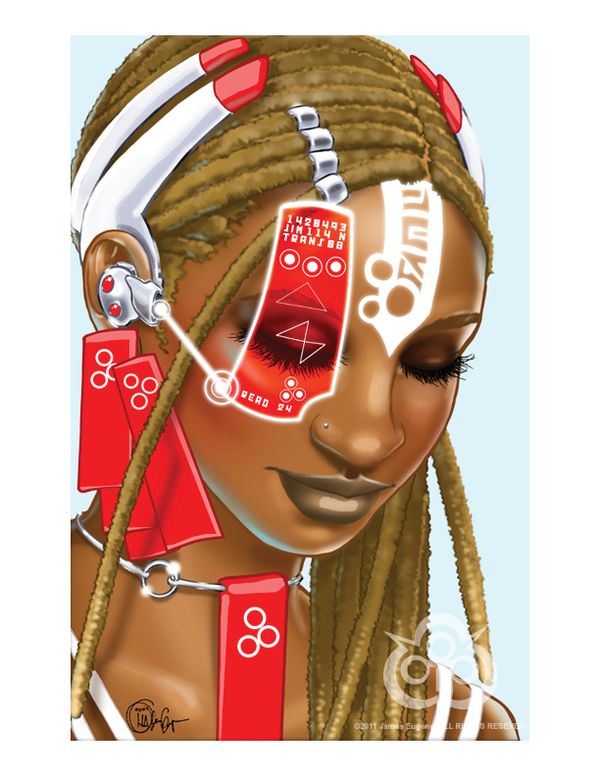

However, the current rise of attention to Afrofuturism in the United States coincides with an increasing awareness among young, well-educated black people who have sought refuge in the alternate realities of graphic novels, movies, and other forms of pop culture as they grapple with making sense of a world where issues of racial justice, environmental degradation, and political uncertainty are major future-facing concerns.

Niama Safia Sandy, an art curator and anthropologist in New York, grew up as a self-described history buff. Pursuing those passions left her wondering about the future for people of color because they were often lacking in the images she saw around her.

“I got tired of going to museums and gallery spaces and not seeing representations of my people,” Sandy related during a FaceTime interview from London, where she was participating in a pop-up art installation of work she curated for Frieze Week. “I felt so strongly that it was time to contextualize the images of black people from around the world and to give credence to where we came from, how we got here and where we are going.”

A journalism and Caribbean studies graduate of Howard University, Sandy shifted her focus from a public relations career to studying the cultures of the African diaspora and Asia. Her studies led her to art galleries and collectors who were experimenting with imagery that depicted a future for black people. In 2015, she pulled together funding for her first curated show, “Black Magic: Afro Pasts/Afro Futures,” at a New York gallery.

“I consider [the works in the exhibition] magical realism,” Sandy said, noting the Afrofuturistic ideas of that show echo through every exhibition she’s done since. “Those themes are encompassing of everything that has been for black people and everything that will be. It’s a way of seeing us move through the world that doesn’t have anything to do with Western impulses.”

Tomorrow: exploring the black future through music