This week’s posts will highlight the small and often overlooked group of African American Mormons who have been members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) almost since its founding on April 6, 1830. Most Mormons are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). The church has never kept official records on the race of its membership, so exact numbers of black members are unknown. Black people have been members of Mormon congregations since its foundation, although the church placed restrictions on proselytization efforts among black people. Before 1978, black membership was small. It has since grown, and in 1997, there were approximately 500,000 black members of the church (about 5% of the total membership), mostly in Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean. Black membership has continued to grow substantially, especially in West Africa, where two temples have been built. In the United States, 3% of members are black.

The initial mission of the church was to proselytize to the everyone, regardless of race or servitude status. When the church moved its headquarters to the slave state of Missouri, the church began changing its policies. In 1833, the church stopped admitting free people of color into the Church. In 1835, the official church policy stated that slaves would not be taught the gospel without their master’s consent, and the following year was expanded to not preach to slaves at all until after their owners were converted.

Jane Manning James had been born free and worked as a housekeeper in Joseph Smith’s home. When she requested the temple ordinances, John Taylor took her petition to the Quorum of the Twelve, but her request was denied. When Wilford Woodruff became president of the church, he compromised and allowed Manning to be sealed to the family of Smith as a servant. This was unsatisfying to Manning as it did not include the saving ordinance of the endowment, and she repeated her petitions. She died in 1908. Church president Joseph F. Smith honored her by speaking at her funeral.

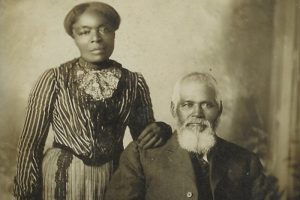

Other notable early black LDS Church members included Green Flake, the slave of John Flake, a convert to the church and from whom he got his name. He was baptized as a member of the LDS Church at age 16 in the Mississippi River, but remained a slave. Following the death of John Flake, in 1850 his widow gave Green Flake to the church as tithing. Some members of the black side of the Flake family say that Brigham Young emancipated their ancestor in 1854, however at least one descendant states that Green was never freed. Samuel D. Chambers was another early African American pioneer. He was baptized secretly at the age of thirteen when he was still a slave in Mississippi. He was unable to join the main body of the church and lost track of them until after the Civil War. He was thirty-eight when he had saved enough money to emigrate to Utah with his wife and son.

Early Mormonism had a range of doctrines related to race with regards to black people of African descent. References to black people, their social condition during the 19th century, and their spiritual place in Western Christianity as well as in Mormon scripture was complicated.

From the beginning, black people have been members of Mormon congregations, and Mormon congregations have always been interracial. When the Mormons migrated to Missouri, they encountered the pro-slavery sentiments of their neighbors. Joseph Smith upheld the laws regarding slaves and slaveholders, and affirmed the curse of Ham as placing his descendants into slavery, “to the shame and confusion of all who have cried out against the South.” With that being said, Smith still remained abolitionist in his actions and doctrines. After the Mormons were expelled from Missouri, Smith took an increasingly strong anti-slavery position, and a few black men were ordained to the LDS priesthood.

The first reference to dark skin as a curse and mark from God in Latter Day Saint writings can be found in the The Book of Mormon, published in the late 1820s. It refers to a group of people called the Lamanites and states that when they rebelled against God they were cursed with “a skin of blackness” (2 Nephi 5:21).

The mark of blackness was placed upon the Lamanites so the Nephites “might not mix and believe in incorrect traditions which would prove their destruction” (Alma 3:7–9). The Book of Mormon records the Lord as forbidding miscegenation between Lamanites and Nephites (2 Nephi 5:23) and saying they were to stay “separated from thee and thy seed [Nephites], from this time henceforth and forever, except they repent of their wickedness and turn to me that I may have mercy upon them” (Alma 3:14).

However, 2 Nephi 26:33 states: “[The Lord] inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come, black and white, bond and free, male and female…and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile.” Although the Lamanites are labelled as wicked, they actually became more righteous than the Nephites as time passed (Helaman 6).

Throughout the Book of Mormon narrative, several groups of Lamanites did repent and lose the curse. The Anti-Nephi-Lehies or Ammonites “open[ed] a correspondence with them [Nephites], and the curse of God did no more follow them” (Alma 23:18). There is no reference to their skin color being changed. Later, the Book of Mormon records that an additional group of Lamanites converted and that “their curse was taken from them, and their skin became white like unto the Nephites… and they were numbered among the Nephites, and were called Nephites” (3 Nephi 2:15–16).

The curse was also put on others who rebelled. One group of Nephites, called Amlicites “had come out in open rebellion against God; therefore it was expedient that the curse should fall upon them”. (Alma 3:18) The Amlicites then put a mark upon themselves. At this point, the author stops the narrative to say “I would that ye should see that they brought upon themselves the curse; and even so doth every man that is cursed bring upon himself his own condemnation.”(Alma 3:19) Eventually, the Lamanites “had become, the more part of them, a righteous people, insomuch that their righteousness did exceed that of the Nephites, because of their firmness and their steadiness in the faith.” (Helaman 6:1)

The Book of Mormon did not countenance any form of curse-based discrimination. It stated that the Lord “denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile”. (2 Nephi 26:33). In fact, prejudice against people of dark skin was condemned more than once, as in this example:

O my brethren, I fear that unless ye shall repent of your sins that their skins will be whiter than yours, when ye shall be brought with them before the throne of God. Wherefore, a commandment I give unto you, which is the word of God, that ye revile no more against them because of the darkness of their skins; neither shall ye revile against them because of their filthiness…” (Jacob 3:8–9).

In 1833, Joseph Smith recorded the following, as verse 79 and 80 of what would become section 101 of the Doctrine and Covenants (D&C).

79 Therefore, it is not right that any man should be in bondage one to another.

80 And for this purpose have I established the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose, and redeemed the land by the shedding of blood.

In the summer of 1833 W. W. Phelps published an article in the church’s newspaper, seeming to invite free black people into the state to become Mormons, and reflecting “in connection with the wonderful events of this age, much is doing towards abolishing slavery, and colonizing the blacks, in Africa.”[4] Outrage followed Phelps’ comments, (Roberts [1930] 1965, p. 378.) and he was forced to reverse his position, which he claimed was “misunderstood”, but this reversal did not end the controversy, and the Mormons were violently expelled from Jackson County, Missouri five months later in December 1833.

Coincidentally, on December 16, 1833, Joseph Smith dictated a passage in the Doctrine and Covenants stating that “it is not right that any man should be in bondage to another.” (D&C Section 101:79).

In 1835, the Church issued an official statement indicating that because the United States government allowed slavery, the Church would not “interfere with bond-servants, neither preach the gospel to, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters, nor meddle with or influence them in the least to cause them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life, thereby jeopardizing the lives of men.” (D&C Section 134:12).

On February 6, 1835, an assistant president of the church, W. W. Phelps, wrote a letter theorizing that the curse of Cain survived the deluge by passing through the wife of Ham, son of Noah, who according to Phelps was a descendant of Cain. (Messenger and Advocate 1:82) In addition, Phelps introduced the idea of a third curse upon Ham himself for “marrying a black wife”. (Messenger and Advocate 1:82) This black wife, according to Phelps, was not just a descendant of Cain, but one of the pre-flood “people of Canaan”, not directly related to the Biblical Canaanites after the flood.

The Mormons have has a mixed history concerning blacks and slavery. They vaciliated back and forth between their perceived inferiority of blacks and the membership in the church. Below is how their stance evolves from 1838-1844.

In 1838, Joseph Smith had the following conversation:

“Elder Hyde inquired about the situation of the negro. I replied, they came into the world slaves mentally and physically. Change their situation with the whites, and they would be like them. They have souls, and are subjects of salvation. Go into Cincinnati or any city, and find an educated negro, who rides in his carriage, and you will see a man who has risen by the powers of his own mind to his exalted state of respectability. The slaves in Washington are more refined than many in high places, and the black boys will take the shine off many of those they brush and wait on. Elder Hyde remarked, “Put them on the level, and they will rise above me.” I replied, if I raised you to be my equal, and then attempted to oppress you, would you not be indignant? […] Had I anything to do with the negro, I would confine them by strict law to their own species, and put them on a national equalization.” (History of the Church, Volume 5, p. 216)

It should be noted here that in 1838, and throughout the 19th century the term “species” was borrowed and commonly used to imply that the black population was inferior.[8] The biological use of the term species was first defined in 1686. [9]

In 1838, Joseph Smith answered the following question while en route from Kirtland to Missouri, as follows: “Are the Mormons abolitionists? No … we do not believe in setting the Negroes free.” (Smith 1977, p. 120)

By 1839 there were about a dozen black members in the Church. Nauvoo, Illinois was reported to have 22 black members, including free and slave, between 1839–1843 (Late Persecution of the Church of Latter-day Saints, 1840).

“In the evening debated with John C. Bennett and others to show that the Indians have greater cause to complain of the treatment of the whites, than the negroes or sons of Cain” (History of the Church 4:501.)

Beginning in 1842, Smith made known his increasingly strong anti-slavery position. In March 1842, he began studying some abolitionist literature, and stated, “it makes my blood boil within me to reflect upon the injustice, cruelty, and oppression of the rulers of the people. When will these things cease to be, and the Constitution and the laws again bear rule?” (History of the Church, 4:544).

On February 7, 1844, Joseph Smith wrote his views as a candidate for president of the United States. The anti-slavery plank of his platform called for a gradual end to slavery by the year 1850 . His plan called for the government to buy the freedom of slaves using money from the sale of public lands.

“My cogitations, like Daniel’s have for a long time troubled me, when I viewed the condition of men throughout the world, and more especially in this boasted realm, where the Declaration of Independence ‘holds these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;’ but at the same time some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours.” (History of the Church, Vol.6, Ch.8, pp. 197–198)

Tomorrow I will start highlighting some the church’s first black members.