Good Morning POU.

![]()

Yes, you may need to pray or mediate first. This week’s topic will be a somber one.

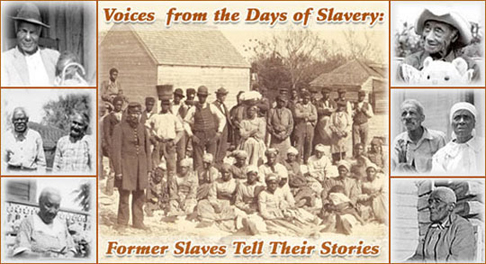

During the 1930s, a massive project to compile the stories of former slaves began by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. It was the simultaneous effort of state-level branches of the FWP in seventeen states, working largely separately from each other. The total collection contains more than 10,000 typed pages representing more than 2000 interviews.

Edited by historian James Mellon, the book Bullwhip Days, contains reminiscences by 29 former slaves about their lives, plus extracts from the recollections of the other 2000 slaves interviewed by the Writers Project, grouped under headings such as “Slave Children, Food and Cooking, Stealing, and Fading Remembrances of Africa” and “Slave Auctions, Forced Breeding, Rape, and Running Away.” The use of the vernacular makes this sometimes difficult going, and may offend some–“Befo’ I’s a field hand, dis nigger never gits whupped, ‘cept for is: Massa use me for huntin’, and use me for de gun rest“–but this extraordinary oral collage will leave no doubts in readers’ minds that, as another ex-slave put it, “Slavery was the worst days that was ever seed in the world.”

William Moore, 80 yrs old, Texas

“Some Sundays we went to church some place. We allus liked to go any place. A white preacher allus told us to ‘bey our masters and work hard and sing and when we die we go to Heaven. Marse Tom didn’t mind us singin’ in our cabins at night, but we better not let him cotch us prayin’.

“Seems like niggers jus’ got to pray. Half they life am in prayin’. Some nigger take turn ’bout to watch and see if Marse Tom anyways ’bout, then they circle theyselves on the floor in the cabin and pray. They git to moanin’ low and gentle, ‘Some day, some day, some day, this yoke gwine be lifted offen our shoulders.’

“Marse Tom been dead long time now. I ‘lieve he’s in hell. Seem like that where he ‘long. He was a terrible mean man and had a indiff’ent, mean wife. But he had the fines’, sweetes’ chillun the Lawd ever let live and breathe on this earth. They’s so kind and sorrowin’ over us slaves.

“Some them chillun used to read us li’l things out of papers and books. We’d look at them papers and books like they somethin’ mighty curious, but we better not let Marse Tom or his wife know it!

Henry Gladney

It come to de time Old Marster have so many slaves he don’t know what to do wid them all. He give some of theem off to his chillun. He give them mostly to his daughters, Mis’ Marion, Mis’ Nancy, and Mis’ Lucretia. I was give to his grandson, Marse John Mobley McCroy, just to wait on him and play wid him. Little Marse John treat me good sometime’ and kick me round sometime’. I see now dat I was just a little dog or monkey, in his heart and mind, dat it ’mused him to pet or kick, as it pleased him.

Malinda Discus

Our master took his slaves to meetin’ with him. There was always something about that I couldn’t understand. They treated the colored folks like animals and would not hesitate to sell and separate them, yet they seemed to think they had souls and tried to make Christians of them.

“The white chillun tries teach me to read and write but I didn’ larn much, ’cause I allus workin’. Mother was workin’ in the house, and she cooked too. She say she used to hide in the chimney corner and listen to what the white folks say. When freedom was ‘clared, marster wouldn’ tell ’em, but mother she hear him tellin’ mistus that the slaves was free but they didn’ know it and he’s not gwineter tell ’em till he makes another crop or two. When mother hear that she say she slip out the chimney corner and crack her heels together four times and shouts, ‘I’s free, I’s free.’ Then she runs to the field, ‘gainst marster’s will and tol’ all the other slaves and they quit work. Then she run away and in the night she slip into a big ravine near the house and have them bring me to her. Marster, he come out with his gun and shot at mother but she run down the ravine and gits away with me.