Good Morning POU! Tonight the Met Gala celebrates “Superfine – Tailoring Black Style”. It’s all about the infamous Black Dandy and Dandyism. Think of the suave Kyle Barker character of Living Single, Fonzworth Bentley, or Jidemma…a classic man!

First a little history about Dandyism.

A dandy is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance and personal grooming, refined language and leisurely hobbies. A dandy could be a self-made man both in person and persona, who emulated the aristocratic style of life regardless of his middle-class origin, birth, and background, especially during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain.

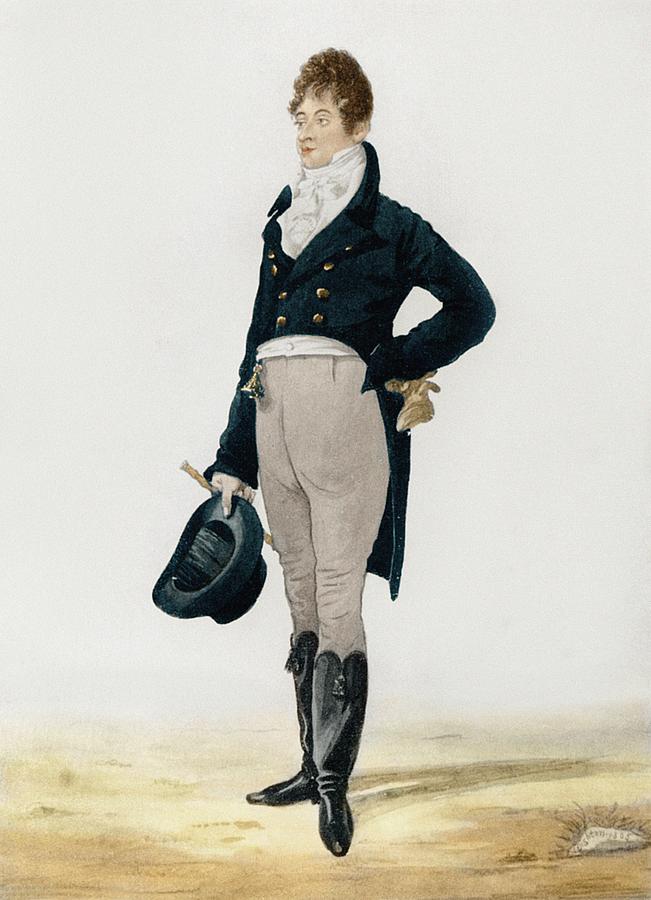

Beau Brummell (George Bryan Brummell, 1778–1840) (pictured above) was the model British dandy since his days as an undergraduate at Oriel College, Oxford, and later as an associate of the Prince Regent (George IV) – all despite not being an aristocrat. He was always bathed, shaved, powdered, perfumed, groomed and immaculately dressed in a dark-blue coat of plain style. Sartorially, the look of Brummell’s tailoring was perfectly fitted, clean and displayed much linen; an elaborately knotted cravat completed the aesthetics of Brummell’s suite of clothes. During the mid-1790s, the handsome Beau Brummell became a personable man-about-town in Regency London’s high society, who was famous for being famous and celebrated “based on nothing at all” but personal charm and social connections.

During the national politics of the Regency era (1795–1837), by the time that Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger had introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act 1795 in order to fund the Britain’s war efforts against France and discouraged the use of foodstuffs as hair powder, the dandy Brummell already had abandoned wearing a powdered wig and wore his hair cut à la Brutus, in the Roman fashion. Moreover, Brummell also led the sartorial transition from breeches to tailored pantaloons, which eventually evolved into modern trousers.

Upon coming of age in 1799, Brummell received a paternal inheritance of thirty thousand pounds sterling, which he squandered on a high life of gambling, lavish tailors, and visits to brothels. Eventually declaring bankruptcy in 1816, Brummell fled England to France, where he lived in destitution and pursued by creditors; in 1840, at the age of sixty-one years, Beau Brummell passed away in a lunatic asylum in Caen, marking the tragic end to his once-glamorous legacy. Nonetheless, despite his ignominious end, Brummell’s influence on European fashion endured, with men across the continent seeking to emulate his dandyism. Among them was the poetical persona of Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron, 1788–1824), who wore a poet’s shirt featuring a lace-collar, a lace-placket, and lace-cuffs in a portrait of himself in Albanian national costume in 1813; Count d’Orsay (Alfred Guillaume Gabriel Grimod d’Orsay, 1801–1852), himself a prominent figure in upper-class social circles and an acquaintance of Lord Byron, likewise embodied the spirit of dandyism within elite British society.

In chapter “The Dandiacal Body” of the novel Sartor Resartus (Carlyle, 1831), Thomas Carlyle described the dandy’s symbolic social function as a man and a persona of refined masculinity:

A Dandy is a Clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office, and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse, and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of Clothes wisely and well: so that as others dress to live, he lives to dress.

Regarding the social function of the dandy in a stratified society, the French poet Baudelaire said that dandies have “no profession other than elegance … no other [social] status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons. … The dandy must aspire to be sublime without interruption; he must live and sleep before a mirror.” Likewise, French intellectuals investigated the sociology of the dandies (flâneurs) who strolled Parisian boulevards.

Black Dandyism

Black dandies have existed since the beginnings of dandyism and have been formative for its aesthetics in many ways. Maria Weilandt in “The Black Dandy and Neo-Victorianism: Re-fashioning a Stereotype” (2021) critiques the history of Western European dandyism as primarily centered around white individuals and the homogenization whiteness as the figurehead of the movement. It is important to acknowledge Black dandyism as distinct and a highly political effort at challenging stereotypes of race, class, gender, and nationality.