Good Morning POU!

A recent article in the Philly Inquirer is the basis for this week’s topic.

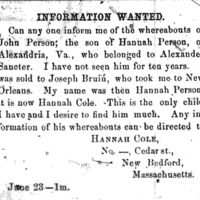

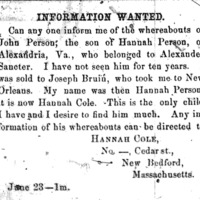

Where is John Person?

Ten years have gone by since his mother, Hannah Cole, last saw him. The pain of his disappearance, the mystery of his whereabouts, and the aching question of whether he is alive or dead have driven her to take out an advertisement in the Christian Recorder, seeking an answer.

“This is the only child I have,” it reads, “and I desire to find him much.”

The date is June 23, 1865, and Cole is on a quest that would consume former slaves such as herself for decades after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, leaving a trail of heartbreak and hope in newspaper classified columns. Mothers search for children sold away. Husbands long for wives torn from them years before. Sons and daughters hope for any clue about a lost parent whom they would “most gratefully receive.”

Under the headline “Information Wanted,” the ads appeared in African American publications around the nation as newly freed slaves established their lives and tried to reunite with loved ones. A potential treasure trove for genealogists and others researching family histories, they have been tucked away on microfilm in church basements and scattered across dozens of obscure library archives.

Now, a project by Villanova University and Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia will make the classified ads easily accessible. The goal of “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery” is an online database of these snapshots from history, which hold names of former slaves, owners, traders, plantation locations, and relatives gone missing. So far, project researchers have uploaded and transcribed 1,000 ads published in six newspapers from 1863 to 1902: the South Carolina Leader in Charleston, the Colored Citizen in Cincinnati, the Free Man’s Press in Galveston, the Black Republican in New Orleans, the Colored Tennessean in Nashville, and the Christian Recorder, the official organ of the African Methodist Episcopal Church denomination published at Mother Bethel.

Some ads had scant details, some had line after line of them. Some were devoid of emotion, others brimmed with it. Some offered monetary rewards, some just a family’s gratitude in return for information.

Until the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery was adopted in December 1865, “people didn’t know if the freedom they attained was secure,” said Judith Giesberg, the project’s leader and the director of Villanova’s graduate program in history. Consequently, they often used terse language in their ads and code words such as “taken from me” instead of “sold away,” evoking their lingering fear and “the incredible silences that speak to people disappearing,” she said.

The Christian Recorder ads often were placed by clients’ pastors, who visited its office at Sixth and Pine Streets and paid $1.50 for a onetime ad, or $4 for one that would run an entire year in the biweekly. The ad purchase usually included a subscription to the paper, which is now published only online.

For researcher Maggie Strolle, 23, a graduate student in history, reading the ads was like watching relatives of a kidnapping victim plead for news, not knowing “if their family member is alive or passed on.”

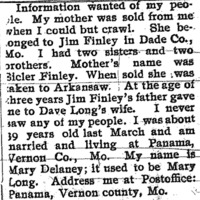

Many waited into a new century. In an ad published April 17, 1902, in the Christian Recorder, 39-year-old Mary Delaney made a request tinged with grief that time had not salved. “Information wanted of my people,” it read. “My mother was sold from me when I could but crawl. She belonged to Jim Finley in Dade Co., Mo. … I never saw any of my people.”

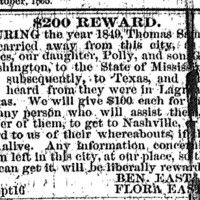

Ben and Flora East offered a reward for news of daughter Polly and son George in an ad in the Colored Tennessean on Oct. 7, 1865. “We will give $100 each for them to any person who will assist them, or either of them, to get to Nashville, or get word to us of their whereabouts, if they are alive,” it read.

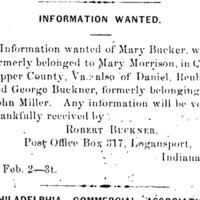

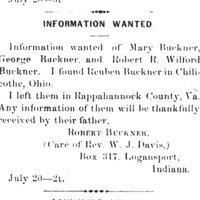

Strolle found only one piece of good news among the ads she read. Robert Buckner, of Logansport, Ind., located his son. “I found Reuben Buckner in Chilicothe, Ohio,” it said. But he had yet to locate his three remaining children, Mary, George, and Robert.

In an informal analysis, Giesberg found that nearly 75 percent of the ads gathered so far were from mothers looking for children, siblings for siblings, and children for parents. Fathers searching for children made up about 7.7 percent; wives looking for husbands, 5 percent; husbands looking for wives, 5.6 percent.

About 66 percent of the families were separated because of slavery; 13 percent suggested escape; and 13 percent were the result of Army enlistment.

Researcher Chris Byrd, 24, who has been uploading and transcribing ads since September, described them as an expression of power by former slaves who until Emancipation had little.

“The latest one I’ve read is 1902,” Byrd said. “So, 40 to 50 years after [Emancipation], people were still trying to find some kind of restitution, exert some control over what had happened to them, and get back what was taken from them.”

Read original article here.