Good Morning POU!

This week’s somber topic will involve stories of forgotten justice for African American families who were victims of racist mobs. Family members snatched away and killed, and no one punished or in some cases even formally accused. Many of the individuals involved may still be alive today, but with evidence long away erased and vanquished, the only hope of justice may lie beyond this world.

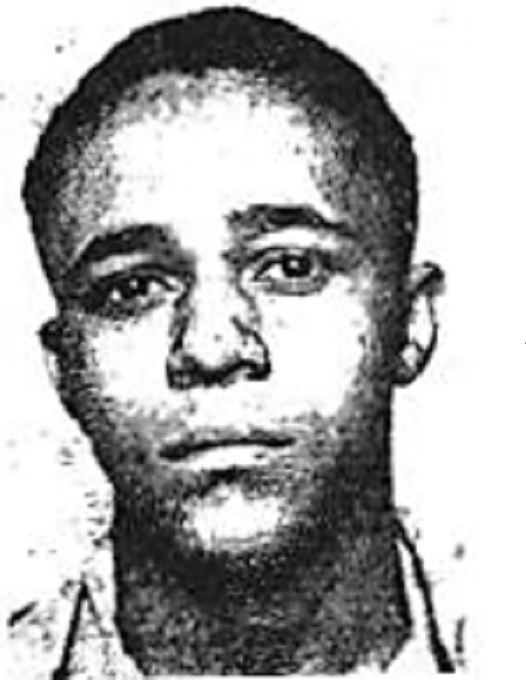

On January 2, 1944, 15-year-old Willie James Howard, a black boy, was kidnapped and lynched by three white men in Suwannee County, Florida, after being accused of sending a love note to the daughter of one of the men.

During Christmas 1943, Willie Howard sent cards to all of his co-workers at the Van Priest Dime Store in Live Oak, Florida. Unlike the other cards, Willie’s card to Cynthia Goff, a white store employee, revealed a youthful crush. His greeting expressed hope that white people would someday like black people and concluded: “I love your name. I love your voice. For a S.H. [sweetheart] you are my choice.”

After reading the card, Cynthia’s father, Phil Goff, brought two friends to the Howard home and demanded to see Willie. Despite his mother’s pleading, the men dragged Willie away, and then kidnapped Willie’s father, James Howard, from work. The men drove the two Howards to the embankment of the Suwanee River, bound Willie’s hands and feet, stood him at the edge of the water, and told him to either jump or be shot. Willie jumped into the cold water below and drowned while his father was forced to watch at gunpoint. Willie’s body was pulled from the river the next day.

Goff and his accomplices admitted to the local sheriff that they took Willie to the river to punish him, but claimed the teen had become hysterical and jumped into the water unprovoked at the thought of being whipped by his father. Fearful for his own life and the other members of his family, James Howard signed a statement supporting Goff’s account. He and his family fled Live Oak three days later.

The following is a 2006 article from The Baltimore Sun regarding the case

60 years later, a cry for justice in Fla. killing

Black teen who liked white girl was taken at gunpoint and drowned in Suwannee River

LIVE OAK, Fla. — It’s a beautiful day, warm and still like summer, but Samuel Beasley doesn’t want to be here. He hasn’t been back since he was a boy, even though he has lived most of his 63 years near the Suwannee River, its shallow waters, its limestone banks, its old oak trees swagged in moss.

Too much pain, 60 years, maybe more. Beasley, gentle and wise and plain-spoken, knows something about this place and its people. Something about what can happen when a black boy likes a white girl. Something that lingers and haunts, that distorts the soul long after a Sunday afternoon years ago.

“The river is evil,” Beasley says softly of this tea-colored ribbon. “It took too many of our people. It took Willie James.”![]()

It is here, just where the water puddles and the sky opens, that Willie James Howard, perhaps the one black youth in town whom everybody believed had a shot at something good, was taken. Just 15, he was dragged from his home at gunpoint, hogtied and forced into the river on Jan. 2, 1944, by three white men for the cultural offense of having a crush on one of their daughters.

He was never seen alive again. But he was never forgotten in the black community, his death affecting the people of Live Oak in sometimes unexpected ways.

“We need what really happened to come out. Everybody needs to know the truth,” says Beasley, a former councilman who was elected as the first black person to serve on the council since Reconstruction.

To appreciate the legacy of Willie James is to understand how three men — a cousin of the dead youth, a funeral director and a Miami historian — men without much in common beyond a deep sense of loss, have come to demand justice.

Eleven years before Emmett Till was lynched for whistling at a white woman in Mississippi, an atrocity that helped launch the civil rights movement, the Willie James Howard story became a cautionary tale about what happens when blacks cross the line. Under the patina of good race relations, progress and Southern hospitality, the story, in all its layers, still resonates in this sawmill town.

“I can remember hearing the story like it was last week,” Beasley says. “It was a huge story. It defined us.”

There were no arrests; there was no trial, just a stunted investigation typical of the civil rights crimes of the era. Among the activists who rallied for justice was a young attorney named Thurgood Marshall, who later would sit on the Supreme Court.

Now, all these years later, Miami historian Marvin Dunn, who is writing a book about lynchings in Florida, has asked Attorney General (and Gov.-elect) Charlie Crist to reopen the case — one of the country’s few remaining unresolved civil rights cases.

“We are interested and reviewing the facts and documents,” says Allison Bethel, head of the state civil rights office.

Though the suspects are long dead, Crist or his successor, Bill McCollum, has the power as attorney general to pursue the case, as a new generation of prosecutors has reopened other cases across the South. These “atonement trials” include last year’s conviction of Edgar Ray Killen in the murders of three civil rights workers in Mississippi.

“The clock does not stop ticking on this kind of offense,” says Dunn, a retired Florida International University professor who ran across the case while researching his book.

“I got so angry when I read about the case. He was just a child,” Dunn says. “This community needs a real investigation. They need healing.”

Willie James Howard was supposed to be somebody. Relatives and friends say he had that hard-to-pinpoint, hard-to-explain thing, uprightness, perhaps, that somehow would have propelled him into respectability, past the grim, one-dimensional landscape of black life in the 1940s South. They talk lovingly about the youth who was so special because he worked at the white-owned dime store downtown.

“Put you in the mind of a Will Smith. He was charming,” says Dorothy DePass, a former classmate. “Everybody knew Willie James, and everybody called him by both names.”

By all accounts, Willie James, also called “Giddy Boy” for his good nature, was smart, funny, good-looking, popular, a great singer — and smitten with Cynthia Goff, a white girl he worked with after school at Van Priest’s. They were the same age, 10th-graders who attended segregated schools a few hundred yards apart.

During Christmas break in 1943, Willie James gave Goff and his other co-workers holiday cards. He signed the one for Goff, “With L [love].”

Perhaps she was vexed that a black youth had given her a card, his gesture too familiar, too presumptuous for the social attitudes of the time. So Willie James wrote an apology dated Jan. 1, 1944.

“I know you don’t think much of our kind but we don’t hate you all. We want to be your friends but you won’t let us. … I wish this was [a] northern state. I guess you call me fresh. Write an[d] tell me what you think of me good or bad. … I love your name. I love your voice, for a S.H. [sweetheart] you are my choice.”

Goff gave the letter to her father, A. Phillip Goff, a former state legislator, who recruited two friends to pay a visit to the Howard home on Jan. 2.

According to the affidavit given by Lula Howard in March 1944, the men took her son from their front porch at gunpoint. They then went to the Bond-Howell Lumber Co., where the boy’s father worked. They picked up James Howard and headed to the river eight miles outside of town.

What happened clouds the town’s memory even today.

“I think this case can open some wounds,” says Jim McCullers, the city clerk and a distant cousin of one of the men accused. “But wrong is wrong.”

What is known for sure: Hours after his mother last saw him, Willie James Howard was dead. The black undertaker was ordered to retrieve the body from the river, and Willie James was buried almost immediately. No farewell, no funeral.

Goff would later tell the Suwannee County sheriff that he and the other men simply wanted to discipline the boy for getting fresh with Cynthia. They admitted binding Willie James to keep him from running while he was being punished by his father. They claimed he became hysterical, and despite being hogtied, jumped into the river.

Suicide, they said. A tragic drowning.

James Howard told a different story. When questioned by the state’s attorney almost six weeks later, he said the men had forced him to watch his only child die.

He said that by the time they got to the river, he knew that his son would never leave alive.

“Willie, I cannot do anything for you now. I’m glad I have belonged to the church and prayed for you,” he recalled in his statement.

He said that Willie James was given a choice: Jump in the river or be shot.

Willie James jumped.

And then the men took Howard back to work. He finished his shift.

“We found out at school the next day. It was so scary, but that was life in the 1940s. We thought the KKK [Ku Klux Klan] were coming to get the rest of us,” says DePass, 78, a retired teacher.

Within days, the Howards had sold their house and moved to Orlando.

“As soon as I saw my sister she told me what happened. She cried and cried and cried. She said she held on to Willie James tight, but they had a gun,” Perry says.

Pressured by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the state briefly reviewed the case. Marshall, who learned of it from a black attorney visiting Live Oak over the Christmas holidays, demanded that Gov. Spessard Holland investigate fully. A grand jury was impaneled but refused to indict.

For half a century — its passage marked by the Till murder, the beginnings of the civil rights movement and the deaths of his parents — Willie James Howard lay in an unmarked grave at the once “coloreds-only” Eastside Cemetery. His ugly death remained a whispered memory until Douglas Udell, a funeral director, was researching the records of a black undertaker whose space he was renting. He found the log of Willie James’ death, with the notation “lynched” and the initials of the three men accused.

The record piqued Udell’s interest and released a flood of memories. His great-grandfather was lynched in the 1920s, his partial skull and pocket knife found when Udell was a teenager.

Udell started looking into the Howard case.

So last year, Udell, a Suwannee County commissioner, bought a headstone for $250 and organized a memorial service. The headstone reads: Willie J. Howard, born 7-13-28, Died 1-2-44, Murdered by Three Racist (sic).

On Jan. 2, 2005, exactly 61 years after Willie James’ death, a service was held at Springfield Baptist Church, where the family had worshiped. The congregation prayed and sang “I’ll Fly Away.”

A typical Live Oak funeral draws about 125 people. Two hundred came to say goodbye to Willie James.

“It was so emotional. People who knew Willie James got up and talked. People cried,” Udell says. “It was like he had died yesterday.”

The procession to the cemetery was led by Live Oak Sheriff Tony Cameron, and the headstone was placed on the grave. A few of Willie James’ cousins rode in a midnight blue limousine.

“I just felt like there was nothing I could do for my granddaddy,” says Udell, but there was something I could do for Willie James.”