This week’s threads will highlight historic black churches in the United States and how the church became a common theme within Afircan-American homes and culture.

The term black church or African-American church refers to Protestant churches that currently or historically have ministered to predominantly black congregations in the United States. While some black churches belong to predominantly African-American denominations, such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), many black churches are members of predominantly white denominations, such as the United Church of Christ (which developed from the Congregational Church of New England).

Most of the first black congregations and churches formed before 1800 were founded by free blacks – for example, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Petersburg, Virginia; and Savannah, Georgia. The oldest black Baptist church in Kentucky, and third oldest in the United States, was founded about 1790 by the slave Peter Durrett.

After slavery was abolished, segregationist attitudes in both the North and the South discouraged and even prevented African Americans from worshiping in the same churches as whites. Freed blacks most often established congregations and church facilities separate from their white neighbors, who were often their former masters. These new churches created communities and worship practices that were culturally distinct from other churches, including unique and empowering forms of Christianity that creolized African spiritual traditions.

African-American churches have long been the centers of communities, serving as school sites in the early years after the Civil War, taking up social welfare functions, such as providing for the indigent, and going on to establish schools, orphanages and prison ministries. As a result, black churches have fostered strong community organizations and provided spiritual and political leadership, especially during the civil rights movement.

Evangelical Baptist and Methodist preachers traveled throughout the South in the Great Awakening of the late 18th century. They appealed directly to slaves, and a few thousand slaves converted. Blacks found opportunities to have active roles in new congregations, especially in the Baptist Church, where slaves were appointed as leaders and preachers. (They were excluded from such roles in the Anglican or Episcopal Church.) As they listened to readings, slaves developed their own interpretations of the Scriptures and found inspiration in stories of deliverance, such as the Exodus out of Egypt. Nat Turner, a slave and Baptist preacher, was inspired to armed rebellion, in an uprising that killed about 50 white men, women, and children in Virginia.

Both free blacks and the more numerous slaves participated in the earliest black Baptist congregations founded near Petersburg, Virginia, Savannah, Georgia and Lexington, Kentucky, before 1800. The slaves Peter Durrett and his wife founded the First African Church (now known as First African Baptist Church) in Lexington, Kentucky about 1790. The church’s trustees purchased its first property in 1815. The congregation numbered about 290 by the time of Durrett’s death in 1823.

Following slave revolts in the early 19th century, including Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, Virginia passed a law requiring black congregations to meet only in the presence of a white minister. Other states similarly restricted exclusively black churches, or the assembly of blacks in large groups unsupervised by whites. Nevertheless, the black Baptist congregations in the cities grew rapidly and their members numbered several hundred each before the Civil War. (See next section.) While mostly led by free blacks, most of their members were slaves.

In plantation areas, slaves organized underground churches and hidden religious meetings, the “invisible church”, where slaves were free to mix evangelical Christianity with African beliefs and African rhythms. With the time, many incorporated Wesleyan Methodist hymns, gospel songs, and spirituals. The underground churches provided psychological refuge from the white world. The spirituals gave the church members a secret way to communicate and, in some cases, to plan rebellion.

Slaves also learned about Christianity by attending services led by a white preacher or supervised by a white person. Slaveholders often held prayer meetings at their plantations. In the South until the Great Awakening, most slaveholders were Anglican if they practiced any Christianity. Although in the early years of the first Great Awakening, Methodist and Baptist preachers argued for the manumission of slaves and abolition, by the early decades of the 19th century, they often had found ways to support the institution. In settings where whites supervised worship and prayer, they used Bible stories that reinforced people’s keeping to their places in society, urging slaves to be loyal and to obey their masters.

In the 19th century, Methodist and Baptist chapels were founded among many of the smaller communities and common planters. During the early decades of the 19th century, they used stories such as the Curse of Ham to justify slavery to themselves. They promoted the idea that loyal and hard-working slaves would be rewarded in the afterlife. Sometimes slaves established their own Sabbath schools to talk about the Scriptures. Slaves who were literate tried to teach others to read, as Frederick Douglass did while still enslaved as a young man in Maryland.

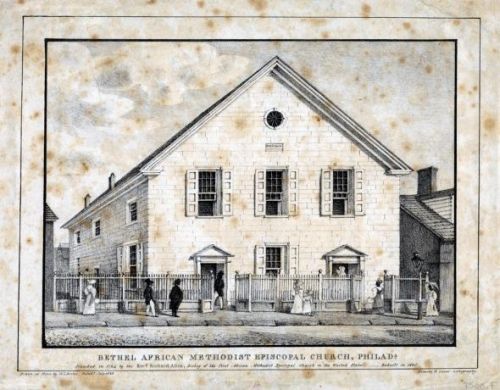

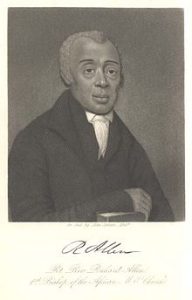

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the A.M.E. Church, is a predominantly African-American Methodist denomination based in the United States. It is the oldest independent Protestant denomination founded by black people in the world. It was founded by the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816 from several black Methodist congregations in the mid-Atlantic area that wanted independence from white Methodists. Allen was consecrated its first bishop in 1816. It began with 8 clergy and 5 churches, and by 1846 had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members. The 20,000 members in 1856 were located primarily in the North. AME national membership (including probationers and preachers) jumped from 70,000 in 1866 to 207,000 in 1876.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the A.M.E. Church, is a predominantly African-American Methodist denomination based in the United States. It is the oldest independent Protestant denomination founded by black people in the world. It was founded by the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816 from several black Methodist congregations in the mid-Atlantic area that wanted independence from white Methodists. Allen was consecrated its first bishop in 1816. It began with 8 clergy and 5 churches, and by 1846 had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members. The 20,000 members in 1856 were located primarily in the North. AME national membership (including probationers and preachers) jumped from 70,000 in 1866 to 207,000 in 1876.

“God Our Father, Christ Our Redeemer, the Holy Spirit Our Comforter, Humankind Our Family”

Derived from Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne’s original motto “God our Father, Christ our Redeemer, Man our Brother”, which served as the AME Church motto until the 2008 General Conference, when the current motto was officially adopted.

The AME Church grew out of the Free African Society (FAS), which Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and other free blacks established in Philadelphia in 1787. They left St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church because of discrimination. Although Allen and Jones were both accepted as preachers, they were limited to black congregations. In addition, the blacks were made to sit in a separate gallery built in the church when their portion of the congregation increased. These former members of St. George’s made plans to transform their mutual aid society into an African congregation. Although the group was originally non-denominational, eventually members wanted to affiliate with existing denominations.