Good Morning POU!

Last week, as the horrific story of Sandra Bland began to unfold, I wondered if a brave investigative journalist would set up residence in Waller County, Texas and dig into the real story of this tragic death. This thought occurred to me while going to Google up information and noting on that day, the google icon was celebrating the birthday of Ida B. Wells. Everyone knows the story of how Ms. Wells risked life and limb to cover the lynchings of African-Americans in the early 20th Century. Her reporting exposed the Jim Crow South’s brutality to the world. Are there reporters now that will hide their identity, risk their personal safety all in the pursuit to expose wrongdoing or is this just a generation of publicity hounds? (looking at Don Lemon, Roland Martin, et al). Who is in Waller County, pouring over court records and personnel files, going over backgrounds and digging into every single second of the last 3 days of Sandra Bland’s life? I hope there is someone there…someone with the bravery and diligence of the journalists that I will feature this week.

Our first featured journalist went undercover as a Domestic to expose the exploitation and horrific working conditions of black women.

Marvel Cooke was a pioneering African American female journalist and political activist. Cooke’s groundbreaking career was spent in a world where she was often the only female African American. Talking about her work for the white-owned newspaper the Compass, she told biographer Kay Mills in 1988, ”there were no black workers there and no women.”

Marvel Jackson was born in 1901. She was the first African American child to be born in the city of Mankato. Her father, Madison Jackson, was the son of a free Ohio farmer. A graduate of the Ohio State University Law School, Madison could not get a job as a lawyer because of racist hiring practices. He worked as a railroad porter. Marvel’s mother, Amy Wood Jackson, was a teacher.

Marvel Jackson moved with her parents to Minneapolis in 1907. They were the first African American residents of the Prospect Park neighborhood. Jackson recalled public meetings and attempts to get her family to leave, but her parents refused. Over time the community grew to accept Marvel and her family.

Jackson was the first African American ever to attend the Sydney Pratt Elementary School in Prospect Park. Her sisters were the second and third. Jackson said in a 1989 interview, “It didn’t bother me at all. I’m by nature, an outgoing person, and I had a lot of friends.” Jackson majored in English at the University of Minnesota, where she was one of five African Americans who graduated in 1925. However, while at the University, Marvel felt her best friend throughout her childhood pretended not to know her rather than explain the inter-racial friendship to her college boyfriend. It was then that Jackson decided, as she stated in an interview with the Washington Press Club years later, “I am not going to live in Minneapolis; I won’t stay there.” She decided to move to Harlem, saying, “It wasn’t south, but it was black, and I decided I wanted to come to Harlem.” She moved there in 1926 to work as an editorial assistant for W.E.B. DuBois at the NAACP publication theCrisis.

In 1928 Jackson became the New York Amsterdam News‘s first female reporter. She helped organize the first union at a black-owned newspaper while working there. In 1931 she organized a successful eleven-week strike at the paper. Jailed twice for picketing, Jackson was quoted as saying, “the bosses are not necessarily in your corner, even if they are your own color.”

Her political beliefs influenced her personal life as well. She ended her engagement to fellow Minnesotan Roy Wilkins, a prominent civil rights activist. Jackson later told a biographer she did not marry Wilkins because he was politically more conservative than she was. She went on to wed world-class sprinter and Olympic-champion sailor Cecil Cooke in 1929.

Cooke’s writing quickly made her a star in mainstream media. She got a job at theCompass, a white-owned newspaper. She was the only African American and the only female reporter. Cooke won recognition for her undercover reporting on New York City domestic workers. She exposed “the horrible working conditions to which these women were subjected.” In her article “The Bronx Slave Market,” Cooke stated, “I was part of the Bronx Slave Market long enough to experience all the viciousness and indignity of system which forces women to the streets in search of work.”

In 1953 she left the Compass and was elected as New York Director of the Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions. In a 1989 interview Cooke described both jobs as the happiest time of her life. During that period, Cooke decided to devote her life to political activism. She became a member of the Communist Party. In 1954 Joseph McCarthy forced her to testify twice before the United States Senate’s Subcommittee on Investigations because of her political beliefs.

The Senate investigation did not slow down her political career. Cooke worked as the national legal defense secretary for 1960s radical Angela Davis. She continued her political activism throughout her life, serving as national vice chairman of the American–Soviet Friendship Committee from 1990 to 1998.

Marvel Cooke died of leukemia on November 29, 2000, in Harlem, New York, at the age of ninety-nine. She spent the last two years of her life writing for the New World Review and helping to sponsor political events. Cooke’s accomplishments and achievements in journalism, politics, and civil rights made her an important figure in each of those fields.

Here are the first three articles in the 5 part series of “The Bronx Slave Market“.

“The Bronx Slave Market”

Marvel Cooke

From The Daily Compass, 1950

PART I

I WAS A PART OF THE BRONX SLAVE MARKET

I was a slave.

I was part of the “paper bag brigade,” waiting patiently in front of Woolworth’s on 170th St., between Jerome and Walton Aves., for someone to “buy” me for an hour or two, or, if I were lucky, for a day.

That is The Bronx Slave Market, where Negro women wait, in rain or shine, in bitter cold or under broiling Sun, to be hired by local housewives looking for bargains in human labor.

It has its counterparts in Brighton Beach, Brownsville and other areas of the city.

Born in the last depression, the Slave Markets are products of poverty and desperation. They grow as employment falls. Today they are growing.

They arose after the 1929 crash when thousands of Negro women, who before then had a “corner” on household jobs because they were discriminated against in other employment, found themselves among the army of the unemployed. Either the employer was forced to do her own household chores or she fired the Negro worker to make way for a white worker who had been let out of less menial employment.

The Negro domestic had no place to turn. She took to the streets in search of employment-and the Slave Markets were born.

Their growth was checked slightly in 1941 when Mayor LaGuardia ordered an investigation of charges that Negro women were being exploited by housewives. He opened free hiring halls in strategic spots in The Bronx and other areas where the Slave Markets had mushroomed.

They were not entirely erased, however, until World War II diverted labor, skilled and unskilled, to the factories.

Today, Slave Markets are starting up again in far-flung sections of the city. As yet, they are pallid replicas of the depression model; but as unemployment increases, as more and more Negro women are thrown out of work and there is less and less money earmarked for full-time household workers, the markets threaten to spread as they did in the middle ’30s, when it was estimated there were 20 to 30 in The Bronx alone.

The housewife in search of cheap labor can easily identify the women of the Slave Market. She can identify them by the dejected droop of their shoulders, or by their work-worn hands, or by the look of bitter resentment on their faces, or because they stand quietly leaning against store fronts or lamp posts waiting for anything – or for nothing at all.

These unprotected workers arc most easily identified. however, by the paper bag in which they invariably carry their work clothes. It is a sort of badge of their profession. It proclaims their membership in “the paper bag brigade”-these women who can be bought by the hour or by the day at depressed wages.

The way the Slave Market operates is primitive and direct and simple-as simple as selling a pig or a cow or a horse in a public market.

The housewife goes to the spot where she knows women in search of domestic work congregate and looks over the prospects. She almost undresses them with her eyes as she measures their strength, to judge how much work they can stand.

If one of them pleases her, the housewife asks what her price is by the hour. Then she beats that price down as low as the worker will permit. Although the worker usually starts out demanding $6 a day and carfare, or $1 an hour and carfare, the price finally agreed upon is pretty low-lower than the wage demanded by public and private agencies, lower than the wage the women of the Slave Market have agreed upon among themselves.

I know because I moved among these women and made friends with them during the late 1930s. I moved among them again several days ago, some ten years later. And I worked on jobs myself to obtain firsthand information.

There is no basic change in the miserable character of the Slave Market. The change is merely in the rate of pay. Ten years ago, women worked for as little as 25 cents an hour. In 1941, before they left the streets to work in the factories, it was 35 cents. Now it is 75 cents.

This may seem like an improvement. But considering how the prices of milk and bread and meat and coffee have jumped during the past decade, these higher wages mean almost no gain at all.

And all of the other evils are still there.

The women of the “paper bag brigade” still stand around in all sorts of weather in order to get a chance to work. They are still forced to do an unspecified amount of work undcr unspecified conditions, with no guarantee that, at the end of the day, they will receive even the pittance agreed upon.

They are still humiliated, day after day, by men who frequent the market area and make immoral advances.

Pointing to this shameful fact, civic and social agencIes have warned that Slave Market areas could easily degenerate into centers of prostitution.

So they could, were it not for the fact that the women themselves resent and reject these advances. They are looking for an honest day’s work to keep body and soul together.

THE BRONX SLAVE MARKET

PART II

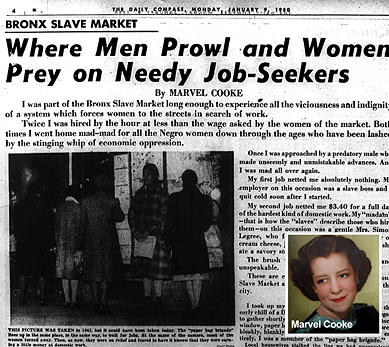

WHERE MEN PROWL AND WOMEN PREY ON NEEDY JOB-SEEKERS

I was part of the Bronx Slave Market long enough to experience all the viciousness and indignity of a system which forces women to the streets in search of work.

Twice I was hired by the hour at less than the wage asked by the women of the market. Both times I went home mad-mad for all the Negro women down through the ages who have been lashed by the stinging whip of economic oppression.

Once I was approached by a predatory male who made unseemly and unmistakable advances. And I was mad all over again.

My first job netted me absolutely nothing. My employer on this occasion was a slave boss and I quit cold soon after I started.

My second job netted me $3.40 for a full day of the hardest kind of domestic work. My “madam”-that is how the “slaves” describe those who hire them-on this occasion was a gentle Mrs. Simon Legree, who fed me three crackers, a sliver of cream cheese, jelly and a glass of coffee while she ate a savory stew.

The brush with the man was degrading and unspeakable.

These are everyday experiences in the Bronx Slave Market and in the markets elsewhere in the city.

• • •

I took up my stand in front of Woolworth’s in the early chill of a December morning. Other women began to gather shortly afterwards. Backs pressed to the store window, paper bags clutched in their hands, they stared bleakly, blankly, into the street. I lost my identity entirely. I was a member of the “paper bag brigade.”

Local housewives stalked the line we had unconsciously formed, picked out the most likely “slaves,” bargained with them and led them off down the street. Finally I was alone. I was about to give up, when a short, stout, elderly woman approached. She looked me over carefully before asking if I wanted a day’s work. I said I did.

“How much you want?”

”A dollar.” (I knew that $1 an hour is the rate the Domestic Workers Union, the New York State Employment Service and other bona fide agencies ask for work by the hour.)

”A dollar an hour!” she exclaimed. “That’s too much. I pay 70 cents.” The bargaining began. We finally compromised on 80 cents. I wanted the job.

“This way.” My “madam” pointed up Townsend Ave. Silently we trudged up the street. My mind was filled with questions, but I kept my mouth shut. At 171st St., she spoke one of my unasked questions:

“You wash windows?”

‘NOT DANGEROUS’

I wasn’t keen on washing windows. Noting my hesitation, she said: “It isn’t dangerous. I live on the ground floor.”

I didn’t think I’d be likely to die from a fall out a first-floor window, so I continued on with her.

She watched me while I changed into my work clothes in the kitchen or her dark three-room, ground-floor apartment. Then she handed me a pail of water and a bottle of ammonia and ordered me to follow her into the bedroom.

“First you are to wash this window,” she ordered.

Each half of the window had six panes. I sat on the window ledge, pulled the top section down to my lap and began washing. The old woman glanced into the room several times during the 20 minutes it took me to finish the job. The window was shining.

I carried my work paraphernalia into the living room, where I was ordered to wash the two windows and the venetian blinds.

As I set about my work again, I saw my employer go into the bedroom.

She came back into the living room, picked up a rag and disappeared again. When she returned a few moments later, I pulled up the window and asked if everything was all right.

“You didn’t do the corners and you missed two panes.” Her tone was accusing.

I intended to be ingratiating because I wanted to finish this job. I started to answer her meekly and offer to go back over the work. I started to explain that the windows were difficult because the corners were caked with paint. I started to tell her I hadn’t missed a single pane.

Of this I was certain. I had checked them off as I did them, with great precision – one, two, three – .

Then I remembered a discussion I’d heard that very morning among members of the “paper bag brigade.” I learned that it is a common device of Slave Market employers to criticize work as a build-up for not paying the worker the full amount of money agreed upon.

“They’ll gyp you at every turn if you let ’em,” one of the women had said.

“They’ll even take 25 cents off your pay for the measly meal they give you. You have to stand up for yourself every inch of the way.”

Suddenly I was angry-angry at this slave boss-angry for all workers everywhere who are treated like a commodity. I slipped under the window and faced the old woman. The moment my feet hit the floor and I dropped the rag into the pail of water, I was no longer a slave.

My voice shaking with anger, I exclaimed: “I washed every single pane and you know it.” Her face showed surprise. Such defiance was something new in her experience. Before she could answer, I had left the pail of dirty water on the living room floor, marched into the kitchen and put on my clothes.

My ex-slave boss watched me while I dressed.

”I’ll pay you for the time you put in,” she offered. I had only worked 40 minutes. I could afford to be magnanimous.

“Never mind. Keep it as a Christmas present from me.” With that, I marched out of the house. It was early. With luck, I could pick up another job.

Again I took up my stand in front of Woolworth’s.

THE BRONX SLAVE MARKET

PART III

‘PAPER BAG BRIGADE’ LEARNS HOW TO DEAL WITH GYPPING EMPLOYERS

I had quit my first job in revolt and now, at 10:30 A.M., I was back in The Bronx Slave Market, looking for my second job of the day.

As I took my place in front of Woolworth’s, on 170th St. near Walton Ave., I found five members of the “paper bag brigade” still waiting around to be “bought” by housewives looking for cheap household labor.

One of the waiting “slaves” glanced at me. I hoped she would be friendly enough to talk.

“Tough out here on the street,” I remarked. She nodded.

“I had one job this morning, but I quit,” I went on. She seemed interested.

“I washed windows for a lady, but I fired myself when she told me my work was no good.” It was as though she hadn’t heard a thing I said. She was looking me over appraisingly.

“I ain’t seen you up here before,” she said. “You’re new, ain’t you?”

ON THE OUTSIDE

I was discovering that you just can’t turn up cold on the market. The “paper hag brigade” is like a fraternity. You must be tried and found true before you are accepted. Until then, you are on the outside,

looking in.

Many of the “new” women are fresh from the South, one worker told me, and they don’t know how to bargain.

“They’ll work for next to nothing,” she said, “and that makes it hard for all of us.” My new friend, probably bored with standing around, decided to forgive my newness and asked about the job I had left. I told her how the fat old lady had accused me of neglecting the window I had so painstakingly washed.

“Oh, that’s the way they all act when they don’t want to give you your full pay.” She brushed off the incident as if it were an everyday occurrence.

“Anyway, you shouldn’t-a agreed to work by the hour. That’s the best way to get gypped. Some of them only want you for an hour or so to clean the worst dirt out of their houses. Then they tell you you’re through. It’s too late by that time to get another job.”

“What should I have done?”

“Just don’t work by the hour,” she repeated laconically. “Work by the day. Ask six bucks and carfare for a three-room apartment.”

EXPERT ADVICE

My new friend proved helpful. She told me all manner of things for which to be on the alert.

“Don’t let them turn the clock back on you,” she warned. “That’s the easiest way to beat you out of your dough. Don’t be afraid to speak up for yourself if they put more work on you than you bargained for.”

I asked whether she had tried to get jobs at the New York State Employment Service on Fordham Road. She said she had a “card,” but that “there are just no jobs up there …. And anyway, I don’t want my name on any records.” When I asked what she meant by that, she became silent and turned her attention to another woman standing beside her. I guessed that she was a relief client.

There seemed little likelihood or another job that morning. I decided to call it a day. As I turned to leave, I saw a woman walking down the street with the inevitable bag under her arm. She looked as if she knew her way around.

“Beg your pardon,” I said as I came abreast of her. ”Are you looking for work, too?”

“What’s it to you?” Her voice was brash and her eyes were hard as steel. She obviously knew her way around and how to protect herself. No foolishness abour her.

“Nothing,” I answered. I felt crushed.

”I’m new up here. Thought you might give me some pointers,” I went on.

“I’m sorry, honey,” she said. “Don’t mind me. I ain’t had no work for so long, I just get cross. What you want to know?”

When I told her about my morning’s experience, she said that “they (the employers) are all bitches.” She said it without emotion. It was spoken as a fact, as if she had remarked, “The sun is shining.”

“They all get as much as they can our your hide and try not to pay you if they can get away with it.”

She, too, worked by the job-“six bucks and carfare.” I asked if she had ever tried the State Employment Service.

“I can’t,” she answered candidly. ”I’m on relief and if the relief folks ever find out I’m working another job, they’ll take it off my check. Lord knows, it’s little enough now, and it’s going to be next to nothing when they start cutting in January.”

She went on down the street. I watched her a moment before I turned toward the subway. I was half conscious that I was being followed. At the corner of 170th St. and Walton Ave., I stopped a moment to look at the Christmas finery in Jack Fine’s window. A man passed me, walked around the corner a few yards on Walton Ave., retraced his steps and stopped by my side.

I crossed Walton Ave. The man was so close on my heels that when I stopped suddenly on the far corner, he couldn’t break his stride. I went back to Jack Fine’s corner. When the man passed me again, he made a lewd, suggestive gesture, winked and motioned me to follow him up Walton Ave.

I was sick to my stomach. I had had enough for one day.