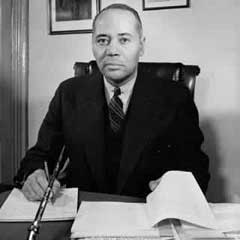

Charles Hamilton Houston (September 3, 1895-April 22, 1950) was a black lawyer who helped play a role in dismantling the Jim Crow laws and helped train future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall. Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow”, he played a role in nearly every civil rights case before the Supreme Court between 1930 and Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Houston’s brilliant plan to attack and defeat Jim Crow segregation by using the inequality of the “separate but equal” doctrine (from the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision) as it pertained to public education in the United States was the master stroke that brought about the landmark Brown decision.

Born in Washington, D.C., Houston prepared for college at Dunbar High School in Washington, then matriculated to Amherst College, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1915. From 1915 to 1917, Houston taught English at Howard University. From 1917 to 1919, he was a First Lieutenant in the United States Infantry, based in Fort Meade, Maryland. Houston later wrote:

“The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

In the fall of 1919, he entered Harvard Law School, earning his Bachelor of Laws degree 1922 and his Doctor of Laws degree in 1923. In 1922, he became the first African-American to serve as an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

After studying at the University of Madrid in 1924, Houston was admitted to the District of Columbia bar that same year and joined forces with his father in practicing law. Beginning in the 1930s, Houston served as the first special counsel to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and therefore was involved with the majority of civil rights cases from then until his death on April 22, 1950.

He later joined Howard Law School’s faculty, establishing a long-standing relationship between Howard and Harvard law schools. While at Howard, he was a mentor to Thurgood can u buy viagra at cvs Marshall, who argued Brown v. Board of Education and was later appointed to the Supreme Court. Houston used his post at Howard to recruit talented students into the NAACP’s legal efforts (among them Marshall and Oliver Hill, the first- and second-ranked students in the class of 1933, both of whom were drafted into organization’s legal battles by Houston).

By the mid-1930s, two separate anti-lynching bills backed by the NAACP had failed to gain passage, and the organization had won a landmark victory against restrictive housing covenants that excluded blacks from particular neighborhoods only to see the achievement undermined by subsequent legal precedents.

Houston struck upon the idea that unequal education was the Achilles heel of Jim Crow. By demonstrating the failure of states to even try to live up to the 1896 rule of “separate but equal,” Houston hoped to finally overturn the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that had given birth to that phrase.

His target was broad, but the evidence was numerous. Southern states collectively spent less than half of what was allotted for white students on education for blacks; there were even greater disparities in individual school districts. Black schools were equipped with castoff supplies from white ones and built with inferior materials. Black facilities appeared to be part of a crude segregationist satire – a design to make black education a contradiction in terms.

Houston designed a strategy of attacking segregation in law schools – forcing states to either create costly parallel law schools or integrate the existing ones. The strategy had hidden benefits: since law students were predominantly male, Houston sought to neutralize the age-old argument that allowing blacks to attend white institutions would lead to miscegenation, or “race-mixing”. He also reasoned that judges deciding the cases might be more sympathetic to plaintiffs who were pursuing careers in law. Finally, by challenging segregation in graduate schools, the NAACP lawyers would bypass the inflammatory issue of miscegenation among young children.

The successful ruling handed down in the Brown decision was testament to the master strategy formulated by Houston.

Source: NAACP website