Good Morning POU! This week’s topic is full of tidbits that amount to “Nothing new is under the sun.”

This week we will look at newspapers and magazines that were published by and for black people in the 18th and early 19th centuries. All now defunct but were very important at getting out information to black people against all odds at the time. Today we’re looking at The Colored American Magazine and the controversy surrounding its publisher, a white investor and the direction of the magazine. Please post your thoughts on what happened (I’m sure it will raise your eyebrows as it did mine…side-eyes for days on this one).

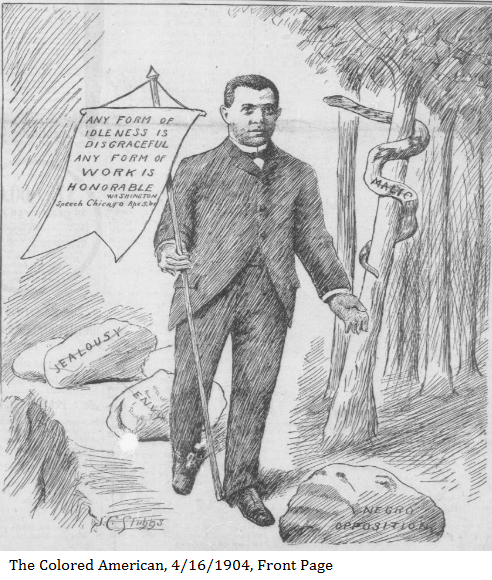

The Colored American Magazine was the first American monthly publication that covered African-American culture. The magazine ran from May 1900 to November 1909. It was initially published out of Boston by the Colored Co-Operative Publishing Company, and from 1904, forward, by Moore Publishing and Printing Company of New York. Pauline Hopkins, its most prolific writer from the beginning, sat on the board as a shareholder, was editor from 1902 to 1904, though her name was not on the masthead until 1903. Hopkins was a journalist, playwright, historian, and literary. In 1904, Booker T. Washington, in a hostile takeover, purchased the magazine and replaced Hopkins with Fred Randolph Moore (1857–1943) as editor.

The Colored American Magazine was founded by Walter Wallace, Jesse W. Watkins, Harper S. Fortune, and Walter Alexander Johnson. The holding company was named The Colored Co-Operative Publishing Company. On May 13, 1903, William H. Dupree (1839–1934), and Jesse W. Watkins purchased the magazine from the Colored Co-operative Publishing Company and renamed the holding company The Colored American Publishing Company. Their aim was to redeem the magazine, financially, and to secure its location in Boston with Hopkins as editor.

John C. Freund (1848–1924), London-born and Oxford educated co-founder and influential editor of two New York magazines, The Music Trades and Musical America, became an outside investor in the magazine in 1903. Recently, beginning around 1996, after the rediscovery of 20 letters in the Pauline Hopkins Collection at the Fisk University Library, scholars show that Hopkins sensed that Freund had conspired with Booker T. Washington to replace her as editor — to quell her outspokenness on racial matters, which in that era, was a prevailing taboo in the minds of many whites. Freund, a white man, and Washington, an African American man, prevailed against Hopkins, an African American woman.

The letters reveal that Hopkins, a well-articulated and influential editor, was a victim of sexism and nuanced racism that was masked by the enlisted cooperation of Washington. Freund apparently believed, and perhaps Washington believed, that directness, about race issues, and racial activism by the magazine would do more harm than good — it would generate greater racial discord in society, harm the economic viability of the magazine, drive away white readership, marginalize the potential for the magazine to win support of whites who otherwise harbored cynical views towards racial equality. Freund felt that the goal of the magazine was to “first—record the work the colored people are doing; second—to make the whites acquainted with it.” Freund opposed writers who felt that advancing bravely also required historic retrospection. In other instances, Freund had rallied support towards helping African Americans succeed and he patronized those who had attained success, which included financial support and published critical acclaim for the People’s Chorus, directed by Emma Azalia Hackley (1867–1922). The upshot was that Hopkins believed, as documented in her letters, that Freund’s altruistic gestures towards helping her and the magazine were actually a ploy to oust her and take control of the magazine’s political content. There are differing views on Freund and Washington’s motives, and differing views on who led the charge, but there is little debate on how Hopkins perceived it.

From the start, the Colored American Magazine was politically engaged, and as conflicts arose among black intellectuals (often symbolized by, but by no means reducible to, Booker T. Washington’s compromise versus W.E.B. Du Bois’s agitation), the Colored American Magazine was secretly purchased by Washington’s agent Fred Moore.

Moore was a strong believer in Booker T. Washington’s racial accommodationist philosophy. In 1904, Booker T. Washington approached Moore and asked him to become an organizer for the National Negro Business League which encouraged blacks to start their own businesses. In 1905, with secret funds from Booker T. Washington (given to him by Freund), Moore became editor and part-owner of Boston’s Colored American Magazine. Moore used the magazine to examine the horrors of lynching and the psychological effects of segregation. He also used it to defend his mentor, Washington, from attacks by critics of the Tuskegee philosophy.

The magazine’s operations were moved away from the radicalism of Boston to New York. Although Hopkins did relocate to New York briefly, Moore’s purchase at the behest of Washington, ended her influence and soon thereafter her career at the magazine. A testament to Hopkins’s popularity was her immediate hiring by the Voice of the Negro, a national monthly which was similar in scope to the Colored American Magazine though it was much more sharply critical of Washington and his associates.