Good Morning POU!

OK, so I know you’re wondering “WUT??” after you saw the topic for this week. Allow me to explain (cuz, trust, its accurate).

Plaçage was a recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies of North America (including the Caribbean) by which ethnic European men entered into the equivalent of common-law marriages with women of color, of African, Native American and mixed-race descent. The term comes from the French placer meaning “to place with”. The women were not legally recognized as wives but were known as placées; their relationships were recognized among the free people of color as mariages de la main gauche or left-handed marriages. They became institutionalized with contracts or negotiations that settled property on the woman and her children, and in some cases gave them freedom if enslaved. The system flourished throughout the French and Spanish colonial periods.

It was most practiced in New Orleans, where planter society had created enough wealth to support the system. It also took place in the cities of Narchez and Biloxi, Mississippi; Mobile, Alabama; St. Augustine and Pensacola, Florida; as well as Saint-Domingue (now the Republic of Haiti). Plaçage became associated with New Orleans as part of its cosmopolitan society.

By 1788, 1500 Creole women of color and black women were being maintained by white men. Certain customs had evolved. It was common for a wealthy, married Creole to live primarily outside New Orleans on his plantation with his white family. He often kept a second address in the city to use for entertaining and socializing among the white elite. He had built or bought a house for his placée and their children. She and her children were part of the society of Creoles of color. The white world might not recognize the placée as a wife legally and socially, but she was recognized as such among the Creoles of color. Some of the women acquired slaves and plantations. Particularly during the Spanish colonial era, a woman might be listed as owning slaves; these were sometimes relatives who she intended to free after earning enough money to buy their freedom.

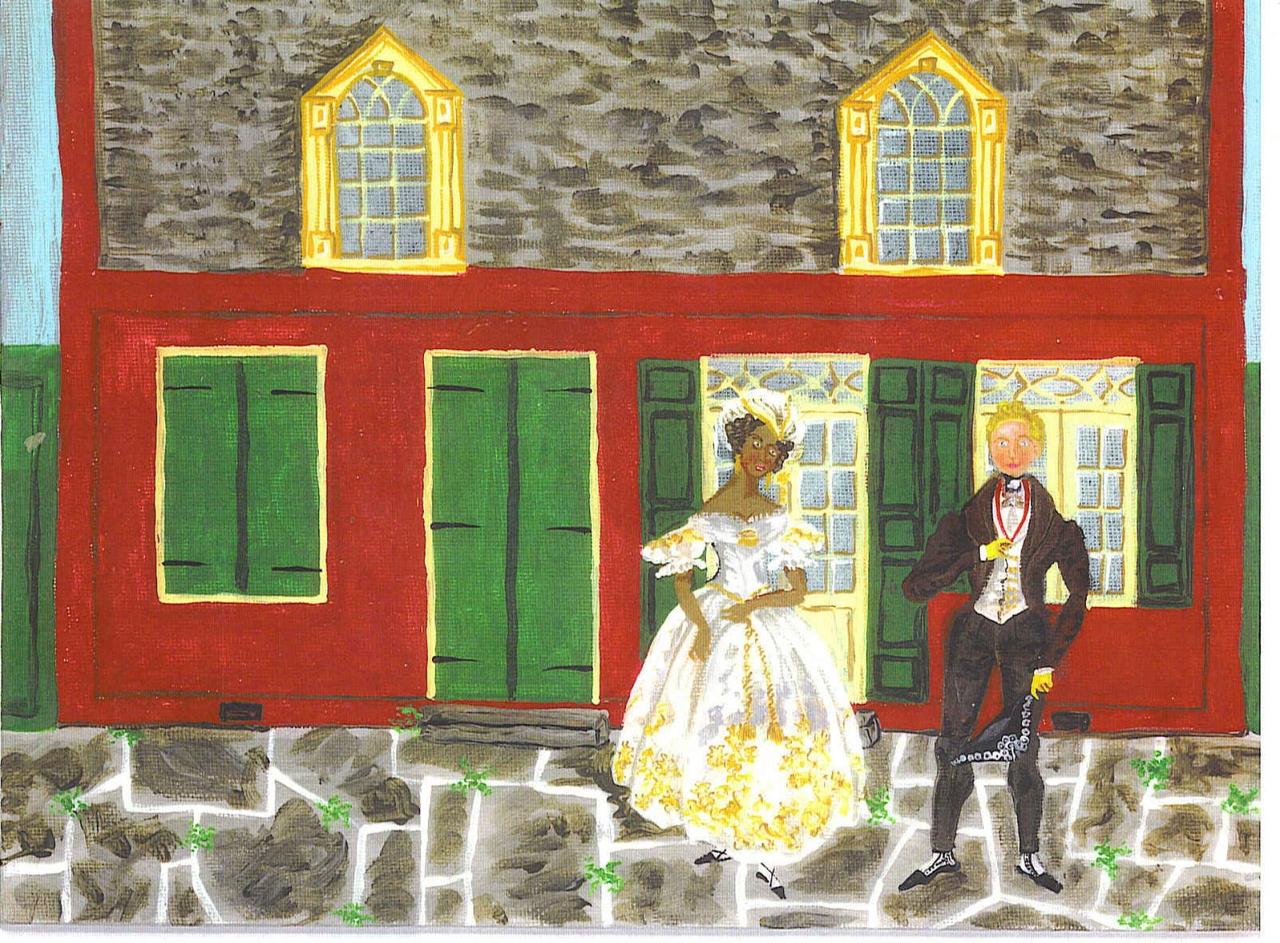

While in New Orleans (or other cities), the man would cohabit with the placée as an official ‘boarder’ at her Creole cottage or house. Many were located near Rampart Street in New Orleans-—once the demarcation line or wall between the city and the frontier. Other popular neighborhoods for Creoles of color were the Faubourg Marigny and Tremé.

If the man was not married, he might keep a separate residence, preferably next door or in the same or next block as his placée. He often took part in and arranged for the upbringing and education of their children. For a time both boys and girls were educated in France, as there were no schools in New Orleans for mixed-race children. As supporting such a plaçage arrangement(s) ran into thousands of dollars per year, it was limited to the wealthy.

(enter my complete side eye, these historians tryna make this shit sound romantic)

Historian Joan Martin says contrary to popular misconceptions, placées were not and did not become prostitutes (bullshit). Creole men of color objected to the practice as denigrating the virtue of Creole women of color, but some, as descendants of white males, benefited by the transfer of social capital. Martin writes, “They did not choose to live in concubinage; what they chose was to survive.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, after Reconstruction and with the reassertion of white supremacy across the former Confederacy, the white Creole historians, Charles Gayarré and Alcée Fortier, wrote histories that did not address plaçage in much detail. They suggested that little race mixing had occurred during the colonial period, and that the placées had seduced or led white Creole men astray. They wrote that the French Creoles (in the sense of having long been native to Louisiana) were ethnic Europeans who were threatened by the spectre of race-mixing like other Southern whites.

(ahhhh, he who hollers the loudest…doing the most dirt)

Gayarré, when younger, was said to have taken a woman of color as his placée and she had their children, to his later shame. He married a white woman late in life. His earlier experience inspired his novel, Fernando de Lemos.

White male colonists, often the younger sons of noblemen, military men, and planters, who needed to accumulate some wealth before they could marry, took women of color as placees before marriage. Merchants and administrators also followed this practice if they were wealthy enough. When the women bore children, they were sometimes emancipated along with their children. Both the woman and her children might take the surnames of the man. When Creole men reached an age when they were expected to marry, some also kept their relationships with their placées. A wealthy white Creole man could have two (or more) families: one legal, and the other not. Their mixed-race children became the nucleus of the class of free people of color or gens de couleur libres in Louisiana and Saint-Domingue.

Upon the death of her protector, the placée and her family could, on legal challenge, expect up to a third of the man’s property. Some white lovers tried, and succeeded, in making their mixed-race children primary heirs over other white descendants or relatives. The women in these relationships often worked to develop assets: acquiring property, running a legitimate rooming-house, or a small business as a hairdresser, marchande (female street or country merchant/vendor), or a seamstress. She could also become a placée to another white Creole. She sometimes taught her daughters to become placées, by education and informal schooling in dress, comportment, and ways to behave. A mother negotiated with a young man for the dowry or property settlement, sometimes by contract, for her daughter if a white Creole were interested in her. A former placée could also marry or to cohabit with a Creole man of color and have more children.

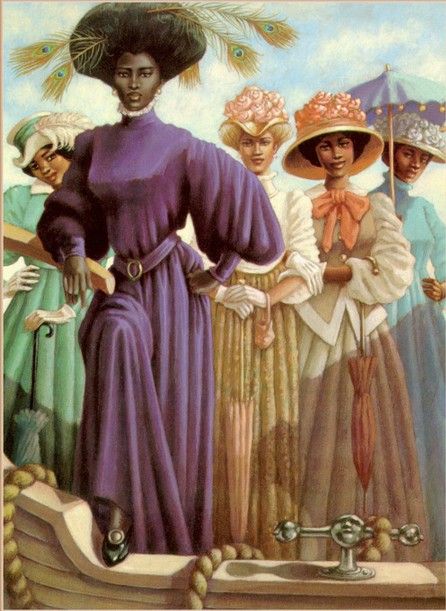

The Quadroon Balls

Creole ladies at one of the last Quadroon Balls

(this Historian quoted in this section is also on some other bullshit. She tends to romanticize this period of history in her writings I suspect because she would like to think of one of her ancestors as some exotic quadroon ho)

The term quadroon is a fractional one referring to a person with one white and one mulatto parent, some courts would have considered one-fourth Black. The quadroon balls were social events designed to encourage mixed-race women to form liaisons with wealthy white men through the system of concubinage known as plaçage. Historian Monique Guillory writes about quadroon balls that took place in New Orleans, the city most strongly associated with these events. She approaches the balls in context of the history of a building the structure of which is now the Bourbon Orleans Hotel. Inside is the Orleans Ballroom, a legendary location for the earliest quadroon balls.

In 1805, a man named Albert Tessier began renting a dance hall where he threw twice weekly dances for free quadroon women and white men only. These dances were elegant and elaborate, designed to appeal to wealthy white men. Although race mixing was prohibited by New Orleans law, it was common for white gentleman to attend the balls, sometimes stealing away from white balls to mingle with the city’s quadroon female population. The principal desire of quadroon women attending these balls was to become plaçee as the mistress of a wealthy gentleman, usually a young white Creole or a visiting European. These arrangements were a common occurrence, Guillory suggests, because the highly educated, socially refined quadroons were prohibited from marrying white men and were unlikely to find Black men of their own status.

A quadroon’s mother usually negotiated with an admirer the compensation that would be received for having the woman as his mistress. Typical terms included some financial payment to the parent, financial and/or housing arrangements for the quadroon herself, and, many times, paternal recognition of any children the union produced. Guillory points out that some of these matches were as enduring and exclusive as marriages. A beloved quadroon mistress had the power to destabilize white marriages and families, something she was much resented for.

According to Guillory, the system of plaçage had a basis in the economics of mixed race. The plaçage of black women with white lovers, Guillory writes, could take place only because of the socially determined value of their light skin, the same light skin that commanded a higher price on the slave block, where light skinned girls fetched much higher prices than did prime field hands. Guillory posits the quadroon balls as the best among severely limited options for these near-white women, a way for them to control their sexuality and decide the price of their own bodies. She contends, “The most a mulatto mother and a quadroon daughter could hope to attain in the rigid confines of the black/white world was some semblance of economic independence and social distinction from the slaves and other blacks”. She notes that many participants in the balls were successful in actual businesses when they could no longer rely on an income from the plaçage system. She speculates they developed business acumen from the process of marketing their own bodies.

Tomorrow: Well known Placees