Good Morning POU!

Have you ever wondered how the poets, novelists, artists and intellectual writers of the Harlem Renaissance actually afforded the ability to travel and pursue their passions? Think about it, it’s the 1920s and 1930s, African Americans as a whole, were not in an economic position to buy artwork and books of poetry and novels. Many of the gifted thinkers of the era traveled abroad, were able to fully develop their works and create “think tanks” with their contemporaries, during one of the most financially depressed eras in American history. How did they do it?

Miss Anne.

The book “Miss Anne in Harlem” takes a look at the white women who provided financial backing to many of the greats of the Harlem Renaissance. The book tries to paint Miss Anne as this whimsical daring woman of means who despite her naivety and blatant racism (which she angrily denies), is a patron of black folks. In a sense, she is. The author, Carla Kaplan (who is herself a Miss Anne with this ‘will roll eyes many times’ effort), provides historical insight into just how the greats of the Harlem Renaissance recognized the need for Miss Anne’s purse, and despite her patronizing ways, learned to adapt to her in order to create an era of unparalleled black creativity.

In 1930, the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, published a poem by Edna Margaret Johnson entitled “A White Girl’s Prayer”. Here are a few lines:

“I writhe in self-contempt, O God —

My Nordic flesh is but a curse:

… Tonight on bended knees I pray:

Free me from my despised flesh

And make me yellow … bronze …

or black”

Johnson wanted to become, what was then called “a voluntary Negro”. Although extreme, “A White Girl’s Prayer” spoke for those whites who longed for the exotic utopia they imagined Harlem could offer.

The press sexualized and sensationalized Miss Anne, often portraying her as either monstrous or insane. To blacks she was unpredictable, which made her dangerous. And so, financial patronage nonwithstanding, blacks did not necessarily welcome her presence, although they often sidestepped saying so publicly or in print. Miss Anne crops up in Harlem Renaissance literature as a minor character—a befuddled dilettante or overbearing patron whose presence in cabarets or political meetings spawns outbreaks of racial violence.

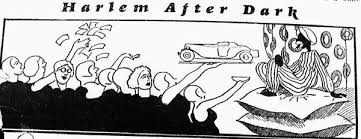

Occasionally, she is caricatured in black newspapers, as in this cartoon image of white women flocking to throw gold, jewels, and cars at one sexy young black man, known in those days as a “sheik.”

Relying on these stock characters, we might believe that she was found only in cabarets, drinking and “jig-chasing” (pursuing black lovers), or enthroned on New York’s Upper East Side, bankrolling black writers. Historians and critics such as Kevin Mumford, Susan Gubar, and Ann Douglas dismiss these women as “slummers” guilty of “sinister . . . vampirism” and pronounce their incursions into Harlem undeserving of serious inquiry. Even Baz Dreisinger’s recent Near Black: White-to-Black Passing in American Culture , the only book of its kind on this subject, mentions just one woman, the journalist Grace Halsell. There are a few individual biographies of these women. These biographies typically dispense with their time in Harlem in a few pages, although it was often the most important and exciting period of their lives.

Some still believe that Miss Anne’s story should remain untold. Often dismissed as a sexual adventurer or a lunatic, Miss Anne may be one of the most reviled but least explored figures in American culture. Miss Anne in Harlem aims to see what can be understood now about this figure’s unlikely, often misunderstood, choices. What can we resurrect about her lived experience of “identity politics,” and how might that be relevant today? What context gave her choices meaning? Why have so few questions been asked about her actions? Could we reconstruct her own view of what she was doing in Harlem without first imposing judgment? One problem with dismissing these women out of hand is that so many of the principal engineers of the Harlem Renaissance sincerely loved them, even if their efforts to become “voluntary Negroes” and speak for blacks also made them nervous.

Sometimes it seems as if Miss Anne engineered her own erasure from the historical record. Some of the most influential white women in Harlem—such as NAACP founder Mary White Ovington, Harlem librarian Ernestine Rose, and philanthropist Amy Spingarn—believed that they were most effective when they drew the least attention to themselves. Some of Harlem’s white women destroyed their own papers. Laboring still under the dictum that a lady’s name should appear in public only upon her birth, marriage, and death and that all other notice of her was unseemly, many of them went to great lengths not to be mentioned. Some of their papers were destroyed by disapproving family members. Some were thrown in with those of their husbands or the famous men with whom they worked. Some of their records remain unprocessed to this day. This lack of materials reflects both the history of gender and the gendered history of Harlem.

It was one thing for white men to go “slumming” in Harlem, where they could enjoy a few hours of “exotic” dancers and “hot” jazz, then grab a cab downtown. But it was another thing altogether for white women to embrace life on West 125th Street. Epitomizing everything that was unrespectable at a time when social respectability meant a great deal more than it does now, a surer way for a white woman to invite derision than to eschew her whiteness or be intimate with a black man. The ease with which Miss Anne’s embrace of black Harlem has been dismissed as either degeneracy or lunacy, rather than explored as a pioneering gesture worthy of attention, indicates how fundamentally she challenged her era’s cherished axioms of racial identity, axioms often held on both sides of the color line, and still valued in many circles today.

So, as you can see, the author of the book on these women is herself, a quintessential MISS ANNE. The aim of the book is to give some sort of understanding to this white woman, to admire her benevolence.

NOPE! This week we will see who these women were, but hear directly from the black people in Harlem and what THEY thought of dear old Miss Anne.