Good morning, POU! This week’s open threads will highlight the events and history of racial relations in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

According to historian Rayford Logan, the nadir of American race relations was the period in the history of the United States from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century, when racism in the country was worse than in any other period in the nation’s history. During this period, African Americans lost many civil rights gained during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynchings, segregation, legal racial discrimination, and expressions of white supremacy increased.

Logan coined the phrase in his 1954 book The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir, 1877–1901. Logan tried to determine the year when “the Negro’s status in American society” reached its lowest point. He argued for 1901, suggesting that relations improved after that; however, others such as John Hope Franklin and Henry Arthur Callis, argued for dates as late as 1923.

The term continues to be used, most notably in books by James Loewen, but it is also used by other scholars. Loewen chooses later dates, arguing that the post-Reconstruction era was, in fact, one of widespread hope for racial equity due to idealistic Northern support for civil rights. In Loewen’s view, the true nadir only began when Northern Republicans ceased supporting Southern blacks’ rights around 1890, and it lasted until the Second World War. This period followed the financial Panic of 1873 and a continuing decline in cotton prices. It overlapped with both the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era and was characterized by the nationwide sundown town phenomenon.

Logan’s focus was exclusively on African Americans in the American South. But the time which he identified also represents the worst period of anti-Chinese discrimination, harassment, and violence on the west coast of the U.S. (and Canada),[6] particularly after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Reconstruction revisionism

In the early part of the 20th century, some white historians put forth the concept of Reconstruction as a tragic period, when Republicans motivated by revenge and profit used troops to force Southerners to accept corrupt governments run by unscrupulous Northerners and unqualified blacks. Such scholars dismissed the idea that blacks could ever be capable of governing.

Notable proponents of this view were referred to as the Dunning School, named after influential Columbia historian William Archibald Dunning. Another Columbia professor, John Burgess, famously wrote that “black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself… created any civilization of any kind.”

The Dunning School’s view of Reconstruction held sway for years. It was represented in D. W. Griffith’s popular movie The Birth of a Nation (1915) and to some extent in Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind (1934). More recent historians of the period have rejected many of the Dunning School’s conclusions and offer a different assessment.

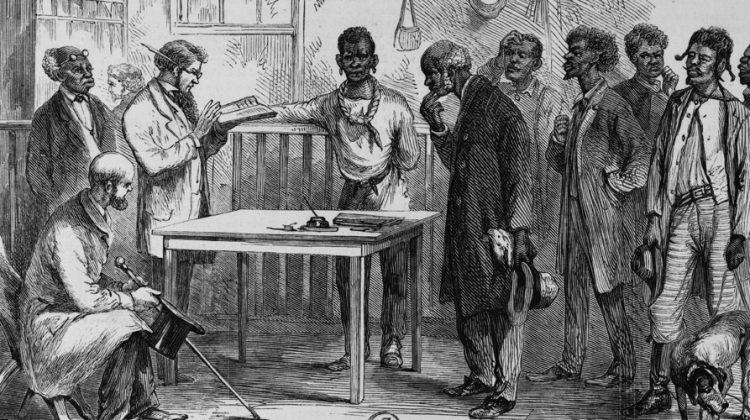

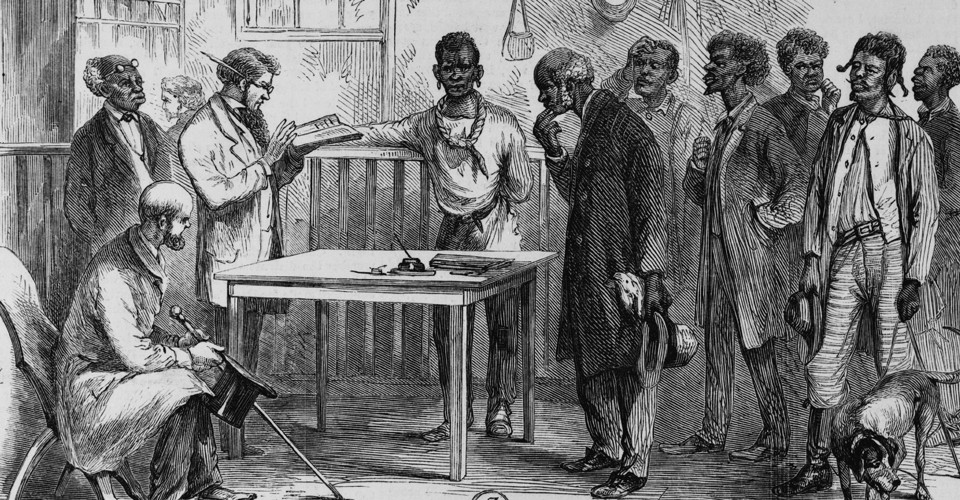

Today’s consensus regards Reconstruction as a time of idealism and hope, with some practical achievements. The Radical Republicans who passed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were, mostly, motivated by a desire to help freedmen. African-American historian W. E. B. Du Bois put this view forward in 1910, and later historians Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner expanded it. The Republican Reconstruction governments had their share of corruption, but they benefited many whites and were no more corrupt than Democratic governments or Northern Republican governments.

The Reconstruction governments established public education and social welfare institutions for the first time, improving education for both blacks and whites, and tried to improve social conditions for the many left in poverty after the long war. No Reconstruction state government was dominated by blacks; in fact, blacks did not attain a level of representation equal to their population in any state.