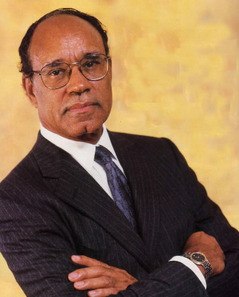

Dr. Harold Freeman, War on Poverty, New York Magazine

Dr. Harold Freeman arrived at Harlem Hospital Center in 1967, having completed his residency at Memorial Sloan-Kettering and his medical training at Howard University “on the cutting edge of surgical oncology.” But nothing could prepare him for what he encountered — the overwhelming majority of his patients were coming to him with hopelessly advanced cases of cancer.

“I was really raring to go out and do what I could,” he recalls, “but this was somewhat of a shock to me — having been trained to do all this cancer work, and then I’m facing late-stage cancer that is too late for me to be effective technically.

” Dr. Freeman started asking questions that might not be included in a typical med-school curriculum. “Technology was not the fundamental answer for the community I was dealing with,” he notes. “What I really needed to know was, why do people come in too late for treatment? What are the reasons?” Dr. Freeman has become the preeminent authority on the subject of poverty and cancer, if not poverty and medicine in general.

A past president of the American Cancer Society, he has been chairman of the President’s Cancer Panel since 1991. (Such credentials run in the family: The descendant of a slave who bought his freedom — and changed his name, hence “Freeman” — Dr. Freeman is a great-grandnephew of Robert Freeman, the first African-American dentist, and a cousin of Robert Weaver, former secretary of HUD and the first African-American cabinet member.) Dr. Freeman’s landmark 1986 report “Cancer in the Economically Disadvantaged” established real links between poverty and the risk factors of cancer.

Back in 1979, he set up two free breast- and cervical-cancer-screening centers in Harlem. In the past ten years, the number of neighborhood patients whose cancer is discovered and is considered to be “highly curable” has jumped from 6 percent to 33 percent. “Dr. Freeman was the first person to analyze something that we now take for granted — that is, cancer as it relates to the population,” says Dr. Charles J. McDonald, national president of the ACS.

“We needed to navigate people from the point of identifying the cancer to the point of treatment,” says Dr. Freeman, who as Harlem Hospital’s director of surgery created the Patient Navigator Program (now emulated around the country), in which an uninsured or low-income patient is assigned an agent-guide to the health-care bureaucracy. “Now you have a system where a person is not just in touch with a clinic, or a building, or a yellow line to follow,” he says. “There’s a real person.”

Since the program has been in effect, the average time it takes an uninsured person to get a biopsy after initial detection is ten days — comparable to the private sector. “We generally talk of the war against cancer like it’s a research war,” says Dr. Freeman. “But don’t stop there: The war against cancer needs to be fought in the neighborhoods where people live and die.”