On September 22, 1906, whites began rampaging through Atlanta’s downtown streets and continued for three days. When it was over, as many as 25 to 40 African Americans were dead, while only two whites died, one of whom was a woman who died of a heart attack after seeing the mob outside her home. The incident made national and even international headlines.

What provoked the riot? According to authors Gregory Mixon and Clifford Kuhn, racial tensions had been building in Atlanta. Some whites resented the wealth of industrious black citizens working and running their businesses in and near the business district. Rival newspapers were vying to see which could print the most sensational accusations of alleged assaults of white women by black males.

The saloons that lined downtown’s Decatur Street, where blacks and whites mingled, concerned many Atlantans. Both candidates in the bitter governor’s race of 1906 further appealed to racial fears and manipulated racial images, proposing the removal of black males entirely from electoral politics. What particularly upset Atlanta’s white citizens was the fear that the city’s segregation and separation of the races was breaking down.

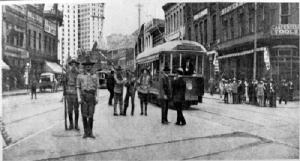

On the afternoon of Saturday, September 22, Atlanta newspapers reported four alleged assaults, none of which were ever substantiated, upon local white women. Extra editions of these accounts, sensationalized with lurid details and inflammatory language intended to inspire fear if not revenge, circulated, and soon thousands of white men and boys gathered in downtown Atlanta. By early evening, the crowd had become a mob; from then until after midnight, they surged down Decatur Street, Pryor Street, Central Avenue, and throughout the central business district, assaulting hundreds of blacks.

The mob attacked black-owned businesses, smashing the windows of black leader Alonzo Herndon’s barbershop. Although Herndon had closed down early and was already at home when his shop was damaged, another barbershop across the street was raided by the rioters—and the barbers were killed. The crowd also attacked streetcars, entering trolley cars and beating black men and women; at least three men were beaten to death.

Many peoples’ lives were forever changed by witnessing these events. For both Walter White, then 13 years of age, and W. E. B. Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University, the riot became a defining moment. What White witnessed, standing in the window of his family’s downtown home, frightened and horrified him. Du Bois secured himself and his wife in their apartment and later did what was completely out of character for him: he purchased a gun that he fully expected to use if his family was threatened. After the riot, Du Bois penned a poem, “The Litany of Atlanta,” a searing and powerful statement.

The riot convinced Du Bois that the best protection for African Americans in the South as well as the North was an organization dedicated to promoting social justice and protection of legal rights. He helped found the NAACP in 1909. Walter White, who did not know Du Bois at the time, later attended Atlanta University and, after graduating, was recruited by the NAACP in 1918 to work in their New York office. Du Bois at the time worked as the founding editor of the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis.

What they both had in common was the 1906 riot.

(MORE)