Good Morning POU!

Today we honor those who lost their lives while serving in the Armed Forces.

This week, our topic will be the African American communities struggle to gain the rights to education. This being a holiday dedicated to the men and women in uniform who sacrificed it all, we will start with those who were able to come home, only to be treated as second class citizens.

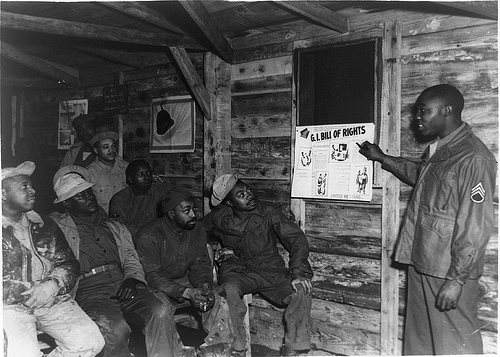

African Americans and the G.I. Bill

This is of particular interest to me as my father benefited from the G.I. Bill after serving in the U.S. Army. I know what the bill meant to my family, and sadly, I know the benefits gained by the bill for black soldiers was nothing close to what it did for their white counterparts. When people ask “but what reparations”, or bemoan affirmative action as “unfair”, or wonder what type of programs do black people think the government can provide to lift up our communities from cycles of oppression….just point to the G.I. Bill, that was created to help white soldiers and expand the white middle class.

Following the second World War, the G.I. Bill of Rights (or, “G.I. bill”) greatly expanded the population of African Americans attending college and graduate school, forming a “crack in the wall of racism that had surrounded the American university system.”

Due to the prevailing social climate that existed in the United States after World War II, one in which racism was a prominent factor, African Americans did not benefit from the provisions of the G. I. Bill nearly as much as their European American counterparts. Though the bill did provide a more level playing field than the one blacks faced during Reconstruction, this is not saying much. Representative John Elliott Rankin, who was also an avid segregationist and racist, sponsored the bill in the House of Representatives. Although the law did not specifically advocate discrimination, the social climate of the time dictated that the law would be interpreted differently for blacks than for whites.

Not only did blacks face discrimination once they returned home after the war, the poverty confronting most blacks during the 1940s and 1950s represented another barrier to harnessing the benefits of the G.I. Bill as it made it problematic to seek an education while labor and income were needed at home. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), because of its strong affiliation to the all-white American Legion and VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars), also became a formidable foe to many blacks in search of an education because it had the power to deny or grant the claims of black G.I.s. Additionally, banks and mortgage agencies refused loans to blacks, making the G.I. Bill even less effective for blacks.

The black middle class failed to keep pace with the white middle class because blacks had fewer opportunities to earn college degrees. In addition to the other obstacles, gaining admission to universities was no easy task for blacks on the G.I. Bill. Most universities had segregationist principles underlying their admissions policies, utilizing either official or unofficial quotas. Even if they could gain admission to universities, public education was in such a poor state for blacks that many of them were not adequately prepared for college level work. Those blacks that were prepared for college level work and gained admission to predominantly white universities still experienced racism on campus.

By 1946, only one fifth of the 100,000 blacks who had applied for educational benefits had been registered in college. Furthermore, historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) came under increased pressure as rising enrollments and strained resources forced them to turn away an estimated 20,000 veterans. HBCUs were already the poorest colleges, resting at the bottom of the educational hierarchy, and served, to most whites, only to keep blacks out of white colleges. The HBCUs resources were stretched even thinner when veterans’ demands necessitated a shift in the curriculum away from the traditional “preach and teach” course of study offered by the HBCUs.

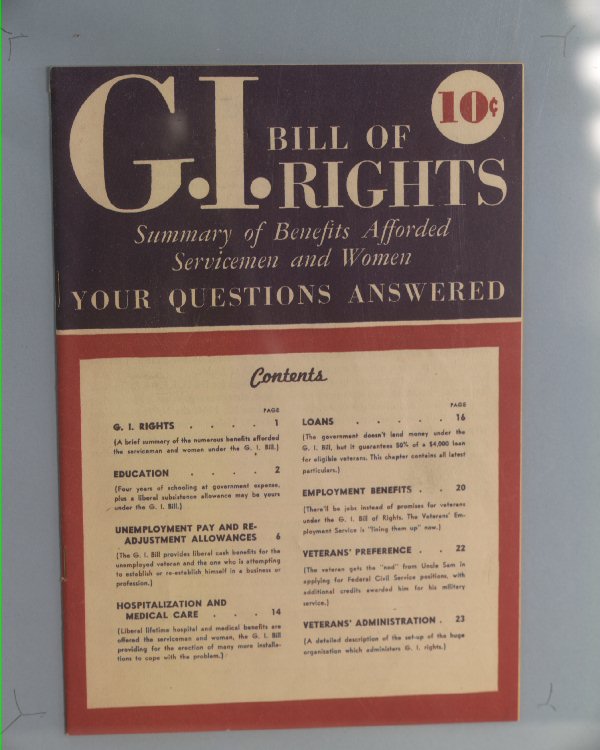

The G.I. Bill touched so much more than just college tuition though. This was the most transformative bill of the 20th Century. The bill provided home loans, job training and other programs to specifically insist returning soldiers – returning white soldiers.

Ira Katznelson (author of When Affirmative Action Was White’: Uncivil Rights) wrote his harshest criticism for the unfair application of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, known as the G.I. Bill of Rights, a series of programs that poured $95 billion into expanding opportunity for soldiers returning from World War II. Over all, the G.I. Bill was a dramatic success, helping 16 million veterans attend college, receive job training, start businesses and purchase their first homes. Half a century later, President Clinton praised the G.I. Bill as ”the best deal ever made by Uncle Sam,” and said it ”helped to unleash a prosperity never before known.”

But Katznelson demonstrates that African-American veterans received significantly less help from the G.I. Bill than their white counterparts. ”Written under Southern auspices,” he reports, ”the law was deliberately designed to accommodate Jim Crow.”

He cites one 1940′s study that concluded it was ”as though the G.I. Bill had been earmarked ‘For White Veterans Only.’ ” Southern Congressional leaders made certain that the programs were directed not by Washington but by local white officials, businessmen, bankers and college administrators who would honor past practices. As a result, thousands of black veterans in the South — and the North as well — were denied housing and business loans, as well as admission to whites-only colleges and universities. They were also excluded from job-training programs for careers in promising new fields like radio and electrical work, commercial photography and mechanics. Instead, most African-Americans were channeled toward traditional, low-paying ”black jobs” and small black colleges, which were pitifully underfinanced and ill equipped to meet the needs of a surging enrollment of returning soldiers.

Though blacks encountered many obstacles in their pursuit of the benefits offered by the G.I. Bill, there were positive aspects of the law for the African American community as well. The bill greatly expanded the population of African Americans attending college and graduate school. In 1940, enrollment at Black colleges was 1.08% of total U.S. college enrollment. By 1950 it had increased to 3.6%. Additionally, the bill led to the passage of the Lanham Act of 1946, which provided for the federal funding of improvement and expansion of HBCUs.

As Hilary Herbold writes, “Clearly, the G.I. Bill was a crack in the wall of racism that had surrounded the American university system. It forced predominantly white colleges to allow a larger number of blacks to enroll, contributed to a more diverse curriculum at many HBCUs, and helped provide a foundation for the gradual growth of the black middle class.” Not only did the G.I. Bill provide the foundation for the black middle class, it educated the generation of African Americans who would help spearhead the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.