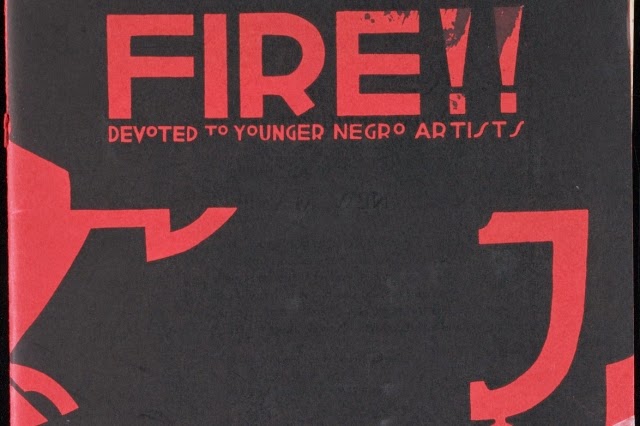

The Niggerati was the name used, with deliberate irony, for a group of young African-American artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. “Niggerati” is a portmanteau of “nigger” and “literati“. The rooming house where writer Wallace Thurman lived, and where that group often met, was similarly christened Niggerati Manor. The group included Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and several of the people behind Thurman’s journal FIRE!! (which lasted for one issue in 1926), such as Richard Bruce Nugent (the associate editor of the journal), Jonathan Davis, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Aaron Douglas.

Hughes, Hurston, and Thurman enjoyed the shock value of referring to themselves as the Niggerati. Hurston’s biographer Valerie Boyd described it as “an inspired moniker that was simultaneously self-mocking and self-glorifying, and sure to shock the stuffy black bourgeoisie”. Hurston was actually the coiner of the name. The quickest wit in what was a very witty group, which encompassed Helene Johnson, Countee Cullen, Augusta Savage, Dorothy West (then a teacher), Harold Jackman, and John P. Davis (a law student at the time), as well as hangers-on, friends, and acquaintances, Hurston dubbed herself the “Queen of the Niggerati”. In addition to Niggerati Manor, the rooming house at 267 West 136th Street where both Thurman and Hughes lived, Niggerati meetings were held at Hurston’s apartment, with a pot on the stove, into which attendees were expected to contribute ingredients for stew. She also cooked okra, or fried Florida eel.

At a time when sexism and homophobia were common, and when the African-American bourgeoisie sought to distance itself from the slavery of the past and seek social equity and racial integration, the Niggerati themselves appeared to be relatively comfortable with their diversity of gender, skin color, and background. After producing FIRE!!, which failed because of a lack of funding, Thurman persuaded the Niggerati to produce another magazine, Harlem. This, too, lasted only a single issue.

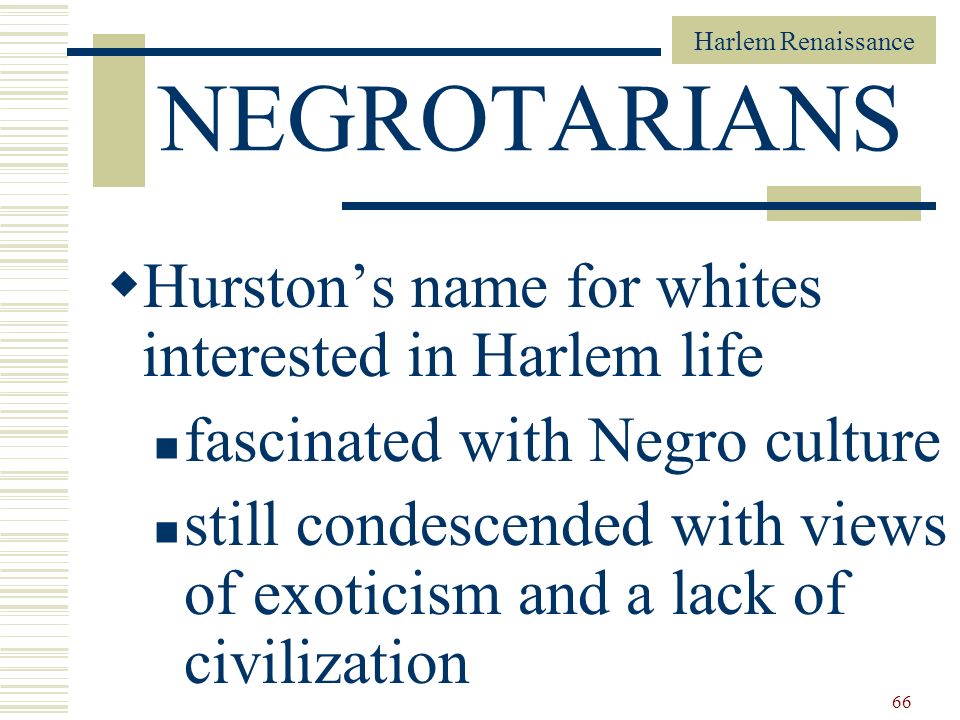

They saw the irony of their dreams as struggling black artists, but dependent on white benefactors to underwrite their artistic endeavors. Yet for the sake of their art, they chose to take the money, no matter what they may have felt about it. These people created together, partied together, fought with each other, and helped each other, as only black folks can and will. While they named their crew the Niggerati, they named those white folks who were interested in their art and coolness and who followed behind them, the Negrotarians. These intellectuals weren’t afraid of their blackness, nor of white reaction to it. They were able to just be their fabulous black selves, the good, the bad, the beautiful, even in the time of strong racial prejudice – and took full advantage of the white people that wanted to be a part of it.

These were the whites Zora Neale Hurston, one of the first Opportunity prize winners, memorably dubbed “Negrotarians.” These comprised several categories: political Negrotarians such as progressive journalist Ray Stannard Baker and maverick socialist types associated with Modern Quarterly (V. F. Calverton, Max Eastman, Lewis Mumford, Scott Nearing); salon Negrotarians such as Robert Chanler, Charles Studin, Carl and Fania (Marinoff) Van Vechten, and Elinor Wylie, for whom the Harlem artists were more exotics than talents; Lost Generation Negrotarians drawn to Harlem on their way to Paris by a need for personal nourishment and confirmation of cultural health, in which their romantic or revolutionary perceptions of African Americans played a key role—Anderson, O’Neill, Georgia O’Keeffe, Zona Gale, Waldo Frank, Louise Bryant, Sinclair Lewis, Hart Crane; commercial Negrotarians such as the Knopfs, the Gershwins, Rowena Jelliffe, Liveright, V. F. Calverton, and music impresario Sol Hurok, who scouted and mined Afro-America like prospectors.

This week we’ll take a look at the relationships between the Niggerati and the Negrotarian.