Good Morning POU!

This week we’ll look at the politics of our hair. The history and economy associated with the hair of African Americans is almost immeasurable. However, its not just the “hair” that we will discuss, but the importance of the hair maintenance community. The roles of barbers and beauticians in the Underground Railroad to the Civil Rights Movement to their roles in electing this country’s first black President. Our “Hair” has been vital to our survival despite the debates on its appearance. We’ll start out featuring prominent men and women in the hair maintenance industry and later this week we’ll talk about the power of the afro and the fear of our naturally thick and kinky hair. This week, we learn, we ARE our hair.

There have been 3 books that provide pivotal information on the history of black barbers in the Underground Railroad.

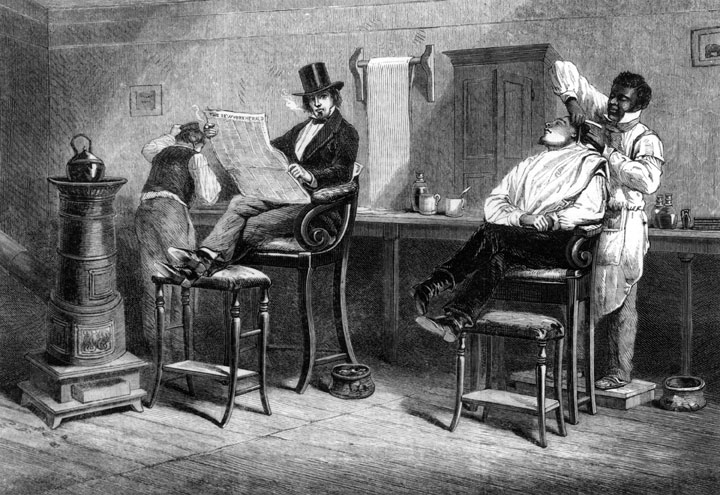

In the book, black barbers, reflected a freed slave who barbered in antebellum St. Louis, may have been “the only men in their community who enjoyed, at all times, the privilege of free speech.” The reason, of course, lay in their temporary—but absolute—power over a client. With a flick of the wrist, 19th-century black barbers could have slit the throats of the white men they shaved.

Besides establishing the modern-day barbershop, these barbers used their skilled trade to navigate the many pitfalls that racism created for ambitious black men. They dominated an upscale market that catered to prosperous white men. At the same time, their respect for labor itself preserved their ties to the black community. Successful barbers assumed leadership roles in their localities, helping to form a black middle class despite pervasive racial segregation. They advocated economic independence from whites and founded insurance companies that became some of the largest black-owned corporations.

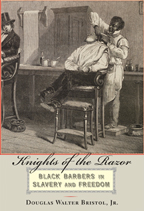

Bristol engagingly narrates this story of skilled blacks and elite whites. More broadly, he offers a thoughtful study of the nuances of race relations and the ingenuity of black enterprise. Knights of the Razor tackles a rich and tangled subject.

In his book, Cutting Along the Color Line, Vassar History Professor Quincy Mills chronicles the cultural history of black barber shops as businesses and civic institutions. Through several generations of barbers, Mills examines the transition from slavery to freedom in the nineteenth century, the early twentieth-century expansion of black consumerism, and the challenges of professionalization, licensing laws, and competition from white barbers. He finds that the profession played a significant though complicated role in twentieth-century racial politics: while the services of shaving and grooming were instrumental in the creation of socially acceptable black masculinity, barbering permitted the financial independence to maintain public spaces that fostered civil rights politics. This sweeping, engaging history of an iconic cultural establishment shows that black entrepreneurship was intimately linked to the struggle for equality.

Tom Calarco, who has written many books about the Underground Railroad, writes in his book The Underground Railroad in the Adirondack Region that “census records generally show that the majority of free blacks in upstate New York who had attained some level of prosperity were barbers. But more significant to a study of the underground Railroad is the inordinate number who were agents or active in organizations that intersected with the Underground Railroad.” This certainly seems to hold true in Schenectady, where at least three nineteenth-century black barbers appeared to have been connected to Underground Railroad activity or to the movement for the abolition of slavery. Calarco looks at the lives of barbers Francis Dana, Richard PG Wright and John Wendall to discover the Underground Railroad running through the barber’s chair.

A vibrant tradition: knights of the razor in the 19th and 21st centuries

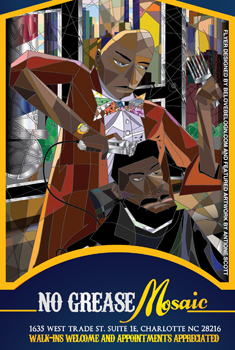

Author Douglas Bristol speaks with the owner of a prominent Charlotte barber shop about the history of the profession.

When Damian Johnson, the co-owner of the No Grease chain of barber shops in Charlotte, North Carolina, began reading my book, Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom, he was struck by the discussion of the movie Barbershop on its first page. The movie is a comedy set in Chicago’s South Side about a 20-something named Calvin, who has inherited a barber shop from his father and is frustrated with the challenges of operating a small business in the inner city. Confronted with foreclosure after mortgaging the shop to finance several get-rich-quick schemes, Calvin sells the business to a loan shark. Through a series of madcap plot developments, Calvin wins back his business after he learns how important barbers are to the African American community.

Damian related to the movie. He grew up in the business—his mother owned a beauty salon—and he had gone off to college determined to find another career. In the end, though, he embraced barbering and wrote his senior marketing paper on how to open a shop like No Grease. Since Damien thought Barbershop captured something important about his experience, he wondered if the rest of Knights of the Razor might remind him of his own life. He told me later that it did.

I was fortunate enough to learn what Damian and his twin brother Jermaine thought about my book over an excellent dinner they bought me in Charlotte on April 13. After reading Knights of the Razor, Damian contacted me about giving a lecture, so I traveled to the Queen City. Damian and Jermaine were superb hosts. I enjoyed shooting pool at their barber shop in the Time Warner Arena. I was also Damian’s guest at a fundraising gala for Johnson C. Smith University, over which he presided as the master of ceremonies. As you can tell, Damian is a great organizer. He managed the next day’s event, my lecture, with considerable aplomb.

Introducing me to the crowd of about 80 people at the Levine Museum of the New South, Damian told the audience how he had accidentally found my book on Amazon and decided, after reading it, that he saw himself as one of the Knights of the Razor.

Damian and Jermaine went on to explain the parallels they found between being black barbers in the 21st century and in the 19th century. Like their predecessors, the twins had to use ingenuity to be successful black businessmen when race posed obstacles. Damian, for example, shared how he and Jermaine convinced their white landlord to finance the purchase of their first shop when no bank would give them a loan. As it happened, their former landlord attended my lecture, and he told the audience what a good investment he had made. Another parallel to their 19th-century counterparts was their first-class shops. In the three No Grease shops, all located in upscale neighborhoods, black barbers wear bow ties while they clip the hair and shave the beards of Charlotte’s black professionals.

Jermaine then explained why he and his brother had chosen the blackface image for the No Grease logo. After learning about minstrel shows while studying drama in college, Jermaine realized that a figure from the minstrel stage could have a double meaning. Blackface invoked negative racial stereotypes, but by taking ownership of the image, Jermaine and his brother could let white businessmen know that they were not playing any games. What W. E. B. DuBois referred to as “double-consciousness,” an awareness of how he looked in the eyes of white people, was a defining trait of the 19th-century black barber. Since he served white rather than black men, understanding white viewpoints was even more central to achieving success than it has been for the Johnson brothers in the 21st century.

The strongest parallel, however, between the Johnson brothers and the intrepid barbers that I wrote about? In the 19th century, the Knights of the Razor were a fraternity. Black barbers took teenagers under their wings as apprentices, trained them for success, and helped them open their own shops. Damian and Jermaine have continued this tradition. A dozen extremely well-dressed graduates of their barber school attended my lecture. One of them, a memorable young man named Dominique, had been working for the Johnsons since he was 17 and is now the foreman of their shop in the Time Warner Arena. So, while I had traveled to Charlotte to tell Damian’s friends what I had learned about his predecessors in the 19th century, he and his brother Jermaine taught me that the vibrant tradition I studied was alive and well in the 21st century.