Good Morning POU!

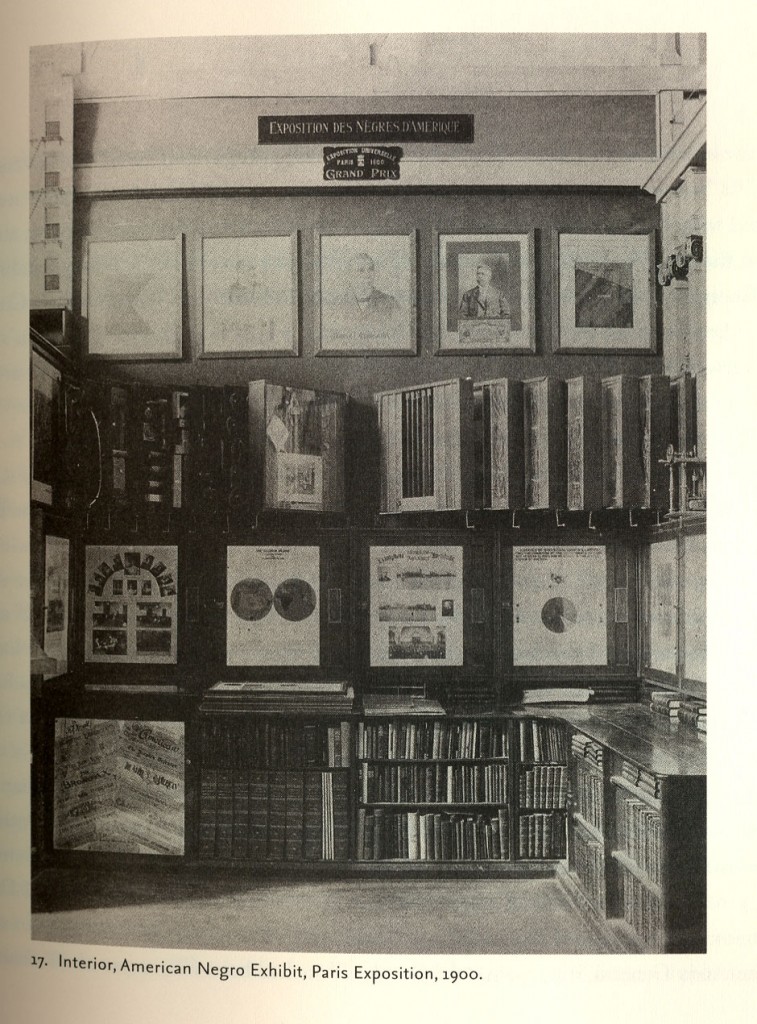

This week we will take a look at the exhibit on African Americans compiled by W.E.B. Du Bois for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris.

First, some background on why this exhibit was created. To do this, we must start with history on the Chicago World Fair of 1893.

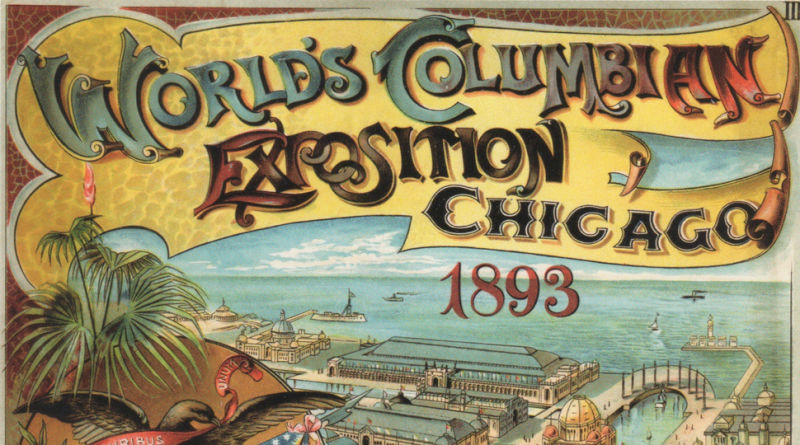

A major development of the nineteenth century was the emergence of world’s fairs, all of which served to entertain visitors and impress them with the technological and cultural advances of Western nations and their colonies which increased exponentially–and dazzlingly–after the 1851 Great Exhibition hosted by England under the auspices of the Prince Consort. By the 1900 world’s fair, which was held in Paris, there had been eleven other expositions, held in such places as Vienna, Philadelphia, Sydney, New Orleans, Barcelona, and Chicago, which introduced a variety of inventions and cultures to awed visitors.

In 1893, Chicago hosted an international exposition, or world’s fair. Called the Columbian Exposition (to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World), the fair featured exhibits from 46 countries, displays of new technologies, and the introduction of many new consumer products.

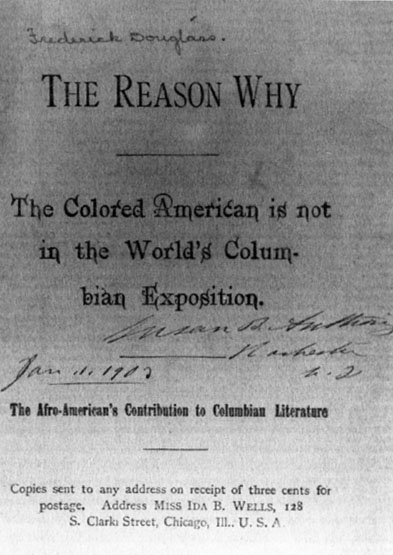

African Americans hoped that the Columbian Exposition would both serve as a source of jobs for African Americans, and also provide an opportunity to showcase their achievements following the Civil War. Unfortunately, their hopes went unfulfilled, as no exhibit space was made available and few jobs at the fair went to African Americans. Frederick Douglass and journalist Ida B. Wells published a pamphlet titled “The Reason Why” to inform people about the exclusion of African Americans from the fair.

Douglass, a former ambassador to Haiti, was asked to serve as one of Haiti’s representatives at the exposition. He and Wells set up shop in the Haitian pavilion, handing out copies of “The Reason Why” to people who passed through. Thus, he was able to some make information about African Americans available to fair-goers.

As Wells described it, the pamphlet

was a clear, plain statement of facts concerning the oppression put upon the colored people in this land of the free and home of the brave. We circulated ten thousand copies of this little book during the remaining three months of the fair. Every day I was on duty at the Haitian building, where Mr. Douglass gave me a desk and spent the days putting this pamphlet in the hands of foreigners.

Ultimately, the fair officials offered to sponsor a special day for African Americans. Wells and many other African Americans considered Negro Day little more than a gesture and were reluctant to participate. Frederick Douglass, however, took the opportunity to spotlight the problems that people of color faced in the United States. Douglass died in 1895, but Wells moved permanently to Chicago and became involved in a wide range of civic and club activities.

The Paris Exposition

Though there were three more expositions of significance by the dawn of WWI (St Louis in 1904, Seattle in 1909, and San Francisco in 1915), the one held in 1900 was unique in that it was the first and last fair to bridge the gap between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This was also the pinnacle of imperialism, and the “nadir of race relations in America.” After witnessing the campaign for the inclusion of African-Americans in the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, African-Americans viewed the Paris Exhibition as another avenue to promote the progress of their people in the thirty-five years since the end of slavery. The year before the fair, W.E.B. Du Bois, a noted sociologist and activist for African-Americans, began to collect material for the display, and focused on “creating charts, maps, and graphs recording the growth of population, economic power, and literacy among African Americans in Georgia.” In conjunction with Daniel A.P. Murray, assistant to the Librarian of Congress, Du Bois was able to assemble a large collection of written works, which included a bibliography of 1400 titles, 200 books, and many of the 150 periodicals published by black Americans.

Du Bois stated that the objective of the exhibit was quadruple, and by displaying it he hoped to illustrate “the History of the American Negro, the Present condition of the Negro, the Education of the Negro, and Literature of the Negro.” he project was backed with a $15,000 budget appropriated from the American government and amounted to numerous artifacts, including “musical compositions, books by African American authors, and the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar, their award-winning display of photographs, books, models, maps, patents, and plans from several black universities, including Atlanta, Fisk, Howard, Hampton, and Tuskegee, showed the world African Americans “studying, examining, and thinking of their own progress, and prospect.”

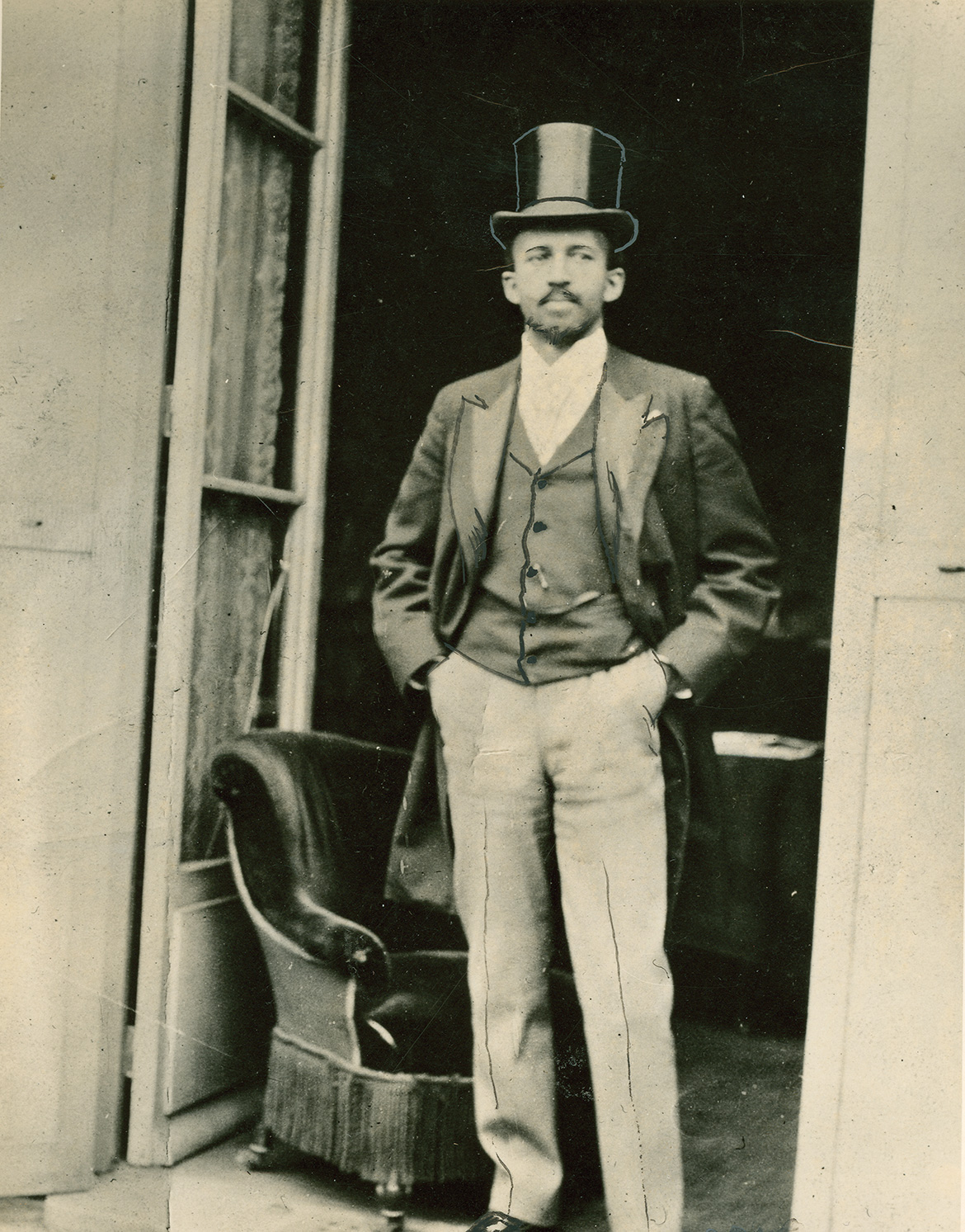

W. E. B. Du Bois at the Paris International Exposition, 1900

One highlight of the exhibit utilized nine model displays to depict the progress of Negroes from slavery to the present day. The models began with the homeless freedman and end[ed] with the modern brick schoolhouse and its teachers. Finally, to illustrate the increase in population of the race and to demonstrate other contributions, there were charts showing population growth, the decline in illiteracy and a record of the more than 350 patents granted to black men since 1834.

Du Bois stated, concerning the exhibit “we have thus, it may be seen, an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.”

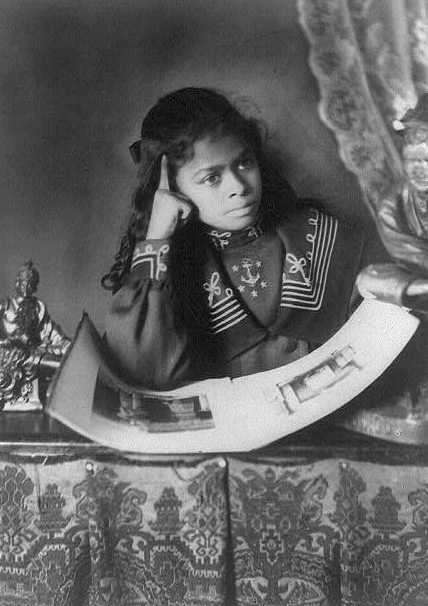

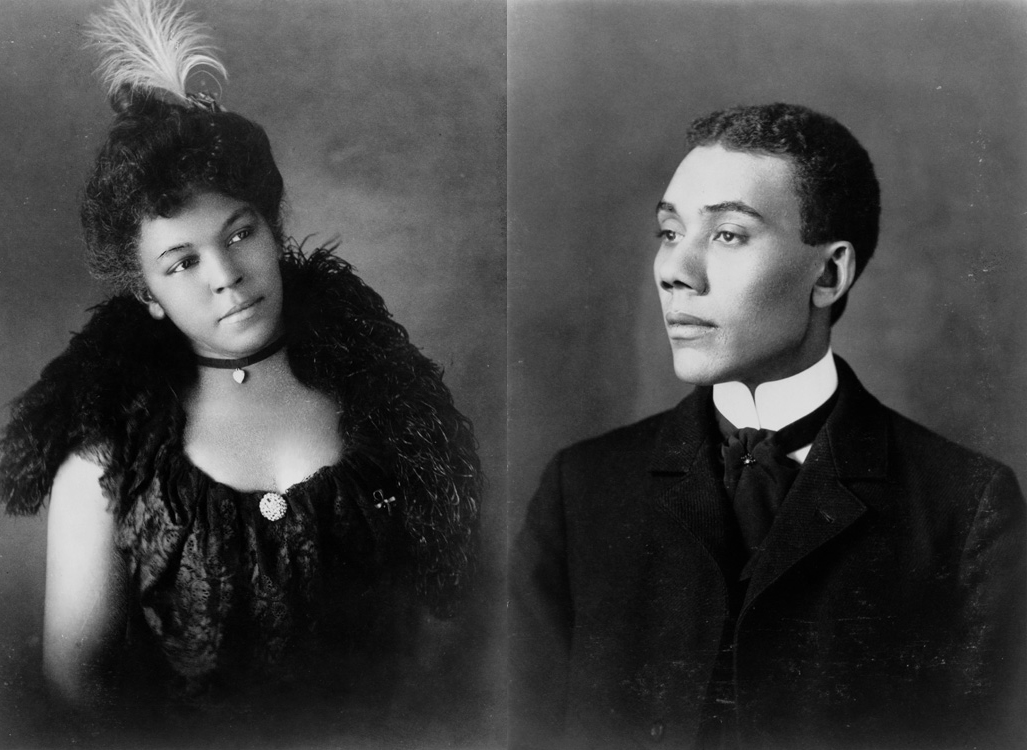

Each open thread this week will feature pictures from the exhibit

Hampton Institute geography class

An African American-owned drugstore in Georgia–CREDIT: “Interior and exterior view of Dr. McDougald’s Drug Store”

NPR reported on 2 December 2003, “W.E.B. Du Bois’ African-American Portraits: Collection Depicts Life for Blacks 35 Years After Civil War,” by Michele Norris — “Some foreigners will think we have nothing for the Negro but the bludgeon and revolver; we shall convince them otherwise.” These are the words of B.D. Woodward, the assistant commissioner-general for the U.S.’s delegation to the 1900 Paris Exposition. He was referring to the “American Negro Exhibit,” pulled together for the Paris Exposition by the young sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois.

Du Bois put on exhibit 500 photographs that symbolized black life in America 35 years after the end of slavery. And he chose with care. The photos, many of them portraits, show the trappings of middle- and upper-class life: ornate clothing, fancy hats, jewelry, confident poses. Du Bois intended the photographs to counteract stereotypes of blacks as poor, uneducated, or as only victims of American racism.