Good Monday Morning POU!

This week will feature amazing women that played in the Negro Leagues as well as women who owned teams and played pivotal roles in the success of the teams.

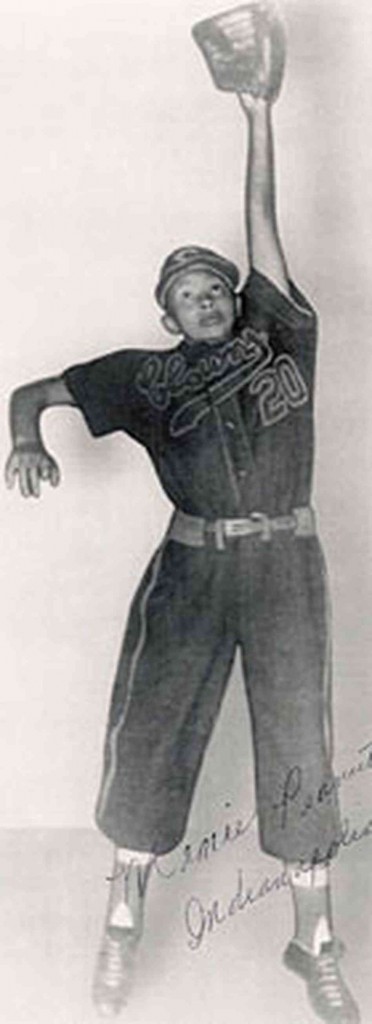

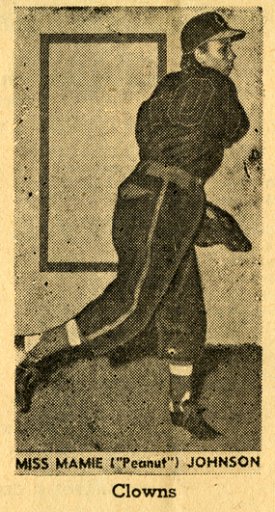

Mamie “Peanut” Johnson

There’s a scene in the movie, A League of Their Own, about the birth of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League during World War II, when the ball gets away from the players on the field. It stops near an African-American woman, who was not participating in the action. She picks it up and whips it back in, the ball popping impressively into the mitt of one of the players.

The moment was a poignant reminder, during an otherwise uplifting story, that this unique opportunity was not available for African-Americans. Not that the league, which lasted from 1943-54, had any written rules against it.

“The people I’ve spoken to didn’t blame the absence of black players on prejudice,” said Bill Madden, author of The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Record Book. “More than one person I interviewed told me they just weren’t up to speed. They said black women at the time weren’t really involved in softball, which is where they got most of their players.”

“We had a few blacks try out, but they just weren’t as good,” said Carl Winsch, manager of the league’s South Bend Blue Sox from 1951-54. But after some consideration, he admitted, “If the league tried harder, shook the bushes more, as we used to say, we might’ve come up with someone.”

That someone could’ve been Mamie “Peanut” Johnson. In fact, the black woman in the movie was intended to represent Johnson, who attended a league tryout in Alexandria, Virginia in the early 50s.

50 years ago Mamie “Peanut” Johnson became a trailblazer by playing in the Negro Leagues of baseball. At 17, Johnson tried out for a spot on a professional women’s team, but was rejected because of her race.

In the late 1940s, she wanted to join the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, and assumed that because Jackie Robinson had broken barriers in the major leagues, the AAGPBL would welcome black players too. The AAGPBL refused to let her try out, but Johnson came away more determined than ever to play ball

“They didn’t let us try out,” Johnson recalls, in a Morning Edition interview with NPR’s Bob Edwards. “They just looked at us like we were crazy as if to say, ‘What do you want?'”

But Johnson insists it’s the best thing that could have happened to her career. The rejection led her to a spot in the men’s buy viagra south africa Negro Leagues, which featured legends such as Satchel Paige, whom she says helped her perfect her curveball. “He just showed me how to grip the ball to keep from throwing my arm away, ‘cause I was so little.”

She was born on September 27, 1935 in Ridgeway, S.C., the daughter of Gentry Harrison and Della Belton Havelow. When she was only seven years old, she would play baseball every day. When she left South Carolina to pursue her college education in 1943, she refused to let anyone or anything interfere with her love of playing baseball. She practiced while pursuing her studies at New York University.

She played with the Alexandria All-Stars, St. Cyprians, and other semi-pro baseball teams around the Washington, D.C. In 1953, at the age of 19, she became a member of the Negro League Indianapolis Clowns baseball club, and pitched for three years. That year, 1953, Johnson finished with an 11-3 record. In 1954, she went 10-1, and in 1955, she finished 12-4. She hit between .252 and .284 in each season. When she wasn’t pitching, she played second base. During her tenure, she won 33 games and lost 8 games. Her batting average ranged from .262 to .284. Of this opportunity, she exclaimed, “Just to know that you were among some of the best male ball players that ever picked up the bat, made all of my baseball moments great moments.” During her three seasons with the Clowns (1953-1955), Johnson played with several Negro Leagues stars, including Hank Aaron.

Her story is recounted in a new book, A Strong Right Arm by Michelle Y. Green.

Edwards asks Johnson how she got along with male ballplayers, who tend to be a “rowdy” bunch. Johnson replies with a laugh: “Well, I can get rowdy, too. That’s no problem. I met some of the nicest gentlemen I could ever meet and I got the highest respect in the world from all of them.”

But, she adds, “you’ve got your gentlemen, and then you’ve got your men.” Some of the “men” don’t know how to act, she says, “but after you prove yourself as to what you came there for, then you don’t have any problem out of them, either. After you strike three or four of them out and, you know, it’s alright.”

“I got to meet and be with some of the best baseball players that ever picked up a bat, so I’m very proud about that.”