This week’s open threads will focus on African Kings and Queens of the past.

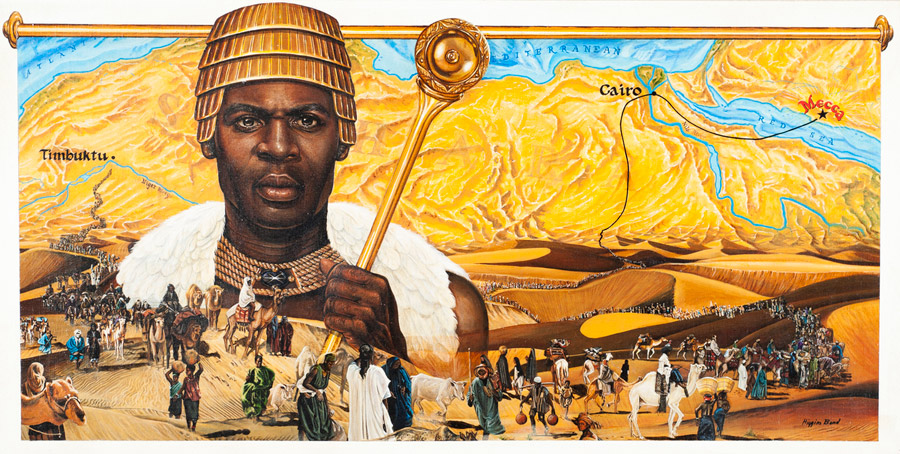

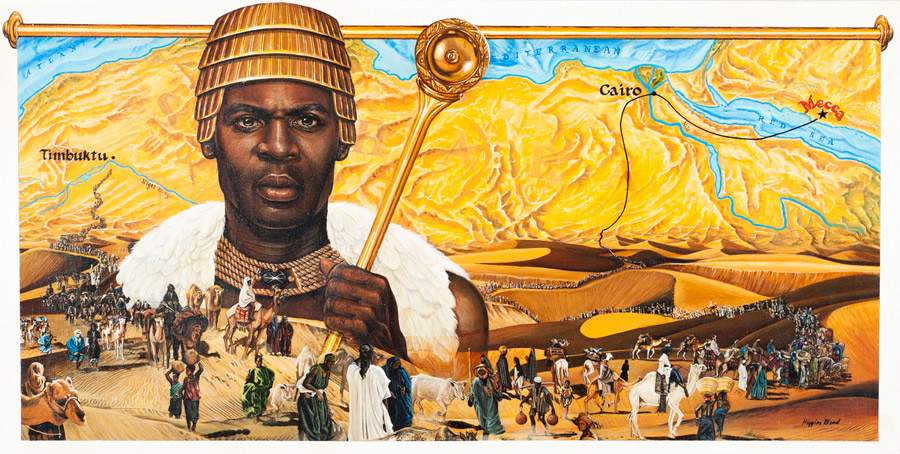

King Mansa Musa I (Emperor Moses) was an important Malian king, ruling from 1312 to 1337 and expanding the Mali influence over the Niger city-states of Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenne. At the time of Musa’s rise to the throne, the Malian Empire consisted of territory formerly belonging to the Ghana Empire in present-day southern Mauritania and in Melle (Mali) and the immediate surrounding areas. Musa held many titles, including Emir of Melle, Lord of the Mines of Wangara, Conqueror of Ghanata, and at least a dozen others.

Musa ruled the Mali Empire and was estimated to have been worth the equivalent of $400 billion in today’s currency, which makes him the richest man to ever walk this earth. The emperor was a master businessman and economist, and gained his wealth through Mali’s supply of gold, salt and ivory, the main commodities for most of the world during that time.

Musa maintained a huge army that kept peace and policed the trade routes for his businesses. His armies pushed the borders of Mali from the Atlantic coast in the west; beyond the cities of Timbuktu and Gao in the east; and from the salt mines of Taghaza in the north to the gold mines of Wangar in the south.

Musa was also a major influence on the University of Timbuktu, the world’s first university and the major learning institution for not just of Africa but the world. Timbuktu became a meeting place of poets, scholars and artists of Africa and the Middle East. Even after Mali declined, Timbuktu remained the major learning center of Africa for many years.

What is known about the kings of the Malian Empire is taken from the writings of Arab scholars, including Al-Umari, Abu-sa’id Uthman ad-Dukkali, Ibn Khaldun, and Ibn Battuta. According to Ibn-Khaldun’s comprehensive history of the Malian kings, Mansa Musa’s grandfather was Abu-Bakr (the Arabic equivalent to Bakari or Bogari, original name unknown − not the sahabiyy Abu Bakr), a brother of Sundiata Keita, the founder of the Malian Empire as recorded through oral histories. Abu-Bakr did not ascend the throne, and his son, Musa’s father, Faga Laye, has no significance in the History of Mali.[5]

Mansa Musa came to the throne through a practice of appointing a deputy when a king goes on his pilgrimage to Mecca or some other endeavor, and later naming the deputy as heir. According to primary sources, Musa was appointed deputy of Abubakari II, the king before him, who had reportedly embarked on an expedition to explore the limits of the Atlantic Ocean, and never returned. The Arab-Egyptian scholar Al-Umari quotes Mansa Musa as follows:

The ruler who preceded me did not believe that it was impossible to reach the extremity of the ocean that encircles the earth (the Atlantic Ocean). He wanted to reach that (end) and was determined to pursue his plan. So he equipped two hundred boats full of men, and many others full of gold, water and provisions sufficient for several years. He ordered the captain not to return until they had reached the other end of the ocean, or until he had exhausted the provisions and water. So they set out on their journey. They were absent for a long period, and, at last just one boat returned. When questioned the captain replied: ‘O Prince, we navigated for a long period, until we saw in the midst of the ocean a great river which was flowing massively.. My boat was the last one; others were ahead of me, and they were drowned in the great whirlpool and never came out again. I sailed back to escape this current.’ But the Sultan would not believe him. He ordered two thousand boats to be equipped for him and his men, and one thousand more for water and provisions. Then he conferred the regency on me for the term of his absence, and departed with his men, never to return nor to give a sign of life.

Musa’s son and successor, Mansa Magha, was also appointed deputy during Musa’s pilgrimage.

During his long return journey from Mecca in 1325, Musa heard news that his army had recaptured Gao. Sagmandia, one of his generals, led the endeavor. The city of Gao had been within the empire since before Sakura’s reign and was an important − though often rebellious − trading center. Musa made a detour and visited the city where he received, as hostages, the two sons of the Gao king, Ali Kolon and Suleiman Nar. He returned to Niani with the two boys and later educated them at his court. When Mansa Musa returned, he brought back many Arabian scholars and architects.

Musa embarked on a large building program, raising mosques and madrasas in Timbuktu and Gao. Most famously the ancient center of learning Sankore Madrasah or University of Sankore was constructed during his reign. In Niani, he built the Hall of Audience, a building communicated by an interior door to the royal palace. It was “an admirable Monument” surmounted by a dome, adorned with arabesques of striking colours. The windows of an upper floor were plated with wood and framed in silver foil, those of a lower floor were plated with wood, framed in gold. Like the Great Mosque, a contemporaneous and grandiose structure in Timbuktu, the Hall was built of cut stone.

During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of the Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian art and architecture scholar, wrote the following about this period: “Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the Niger Delta was very densely populated.”

It is recorded that Mansa Musa traveled through the cities of Timbuktu and Gao on his way to Mecca, and made them a part of his empire when he returned around 1325. He brought architects from Andalusia, a region in Spain, and Cairo to build his grand palace in Timbuktu and the great Djinguereber Mosque that still stands today.

Timbuktu soon became a center of trade, culture, and Islam; markets brought in merchants from Hausaland, Egypt, and other African kingdoms, a university was founded in the city (as well as in the Malian cities ofDjenné and Ségou), and Islam was spread through the markets and university, making Timbuktu a new area for Islamic scholarship. News of the Malian empire’s city of wealth even traveled across the Mediterranean to southern Europe, where traders from Venice, Granada, and Genoa soon added Timbuktu to their maps to trade manufactured goods for gold.

The University of Sankore in Timbuktu was restaffed under Musa’s reign with jurists, astronomers, and mathematicians. The university became a center of learning and culture, drawing Muslim scholars from around Africa and the Middle East to Timbuktu.

In 1330, the kingdom of Mossi invaded and conquered the city of Timbuktu. Gao had already been captured by Musa’s general, and Musa quickly regained Timbuktu and built a rampart and stone fort, and placed a standing army to protect the city from future invaders.

While Musa’s palace has since vanished, the university and mosque still stand in Timbuktu today.

The death of Mansa Musa is highly debated among modern historians and the Arab scholars who recorded history of Mali. When compared to the reigns of his successors, son Mansa Maghan (recorded rule from 1332 to 1336) and older brother Mansa Suleyman (recorded rule from 1336 to 1360), and Musa’s recorded 25 years of rule, the calculated date of death is 1332. Other records declare Musa planned to abdicate the throne to his son Maghan, but he died soon after he returned from Mecca in 1325. Further, according to an account by Ibn-Khaldun, Mansa Musa was alive when the city of Tlemcen in Algeria was conquered in 1337, as he sent a representative to Algeria to congratulate the conquerors on their victory.

Information courtesy of http://atlantablackstar.com/2013/12/07/10-african-kings-and-queens-whose-stories-must-be-told-on-film/2/.