Good Morning POU!

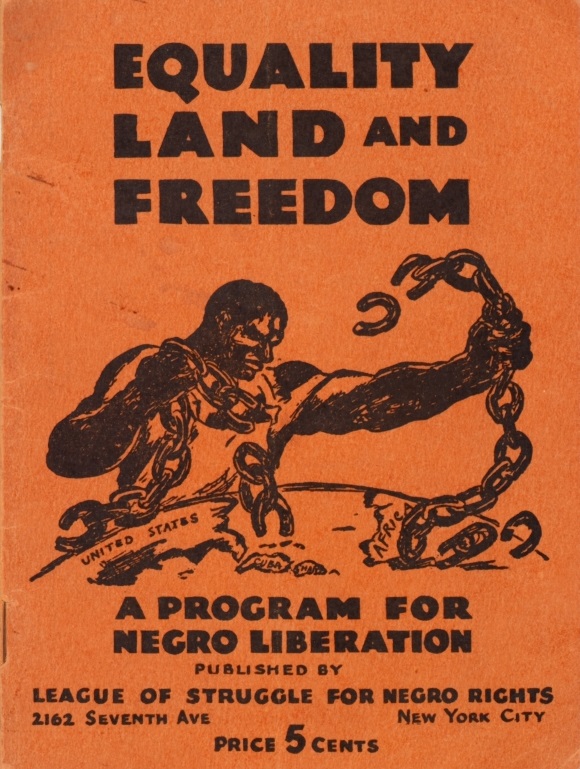

We look at the final years of the large influence Communism had on African Americans. We continue at the point of the National Negro Congress as it morphs into the Civil Rights Congress.

In 1946, the National Negro Congress (NNC) and the International Labor Defense (ILD) merged to form the Civil Rights Congress. The CRC continued its activities during the height of postwar attacks on the Communist Party, denouncing discrimination in the judicial system, segregated housing, and other forms of discrimination that blacks faced in both the North and the South.

The party had hopes of remaining in the mainstream of American politics in the postwar era. Benjamin J. Davis, Jr.. ran for and won a seat on the City Council in New York City in 1945, advertising his membership in the Communist Party and drawing on both black and white support. That era did not last. New York City changed the rules for electing members of the City Council after Davis’ election. Davis lost the next race in 1949 by a landslide to an anti-communist candidate. He was under indictment for advocating the overthrow of the United States government, and this did not help his candidacy.

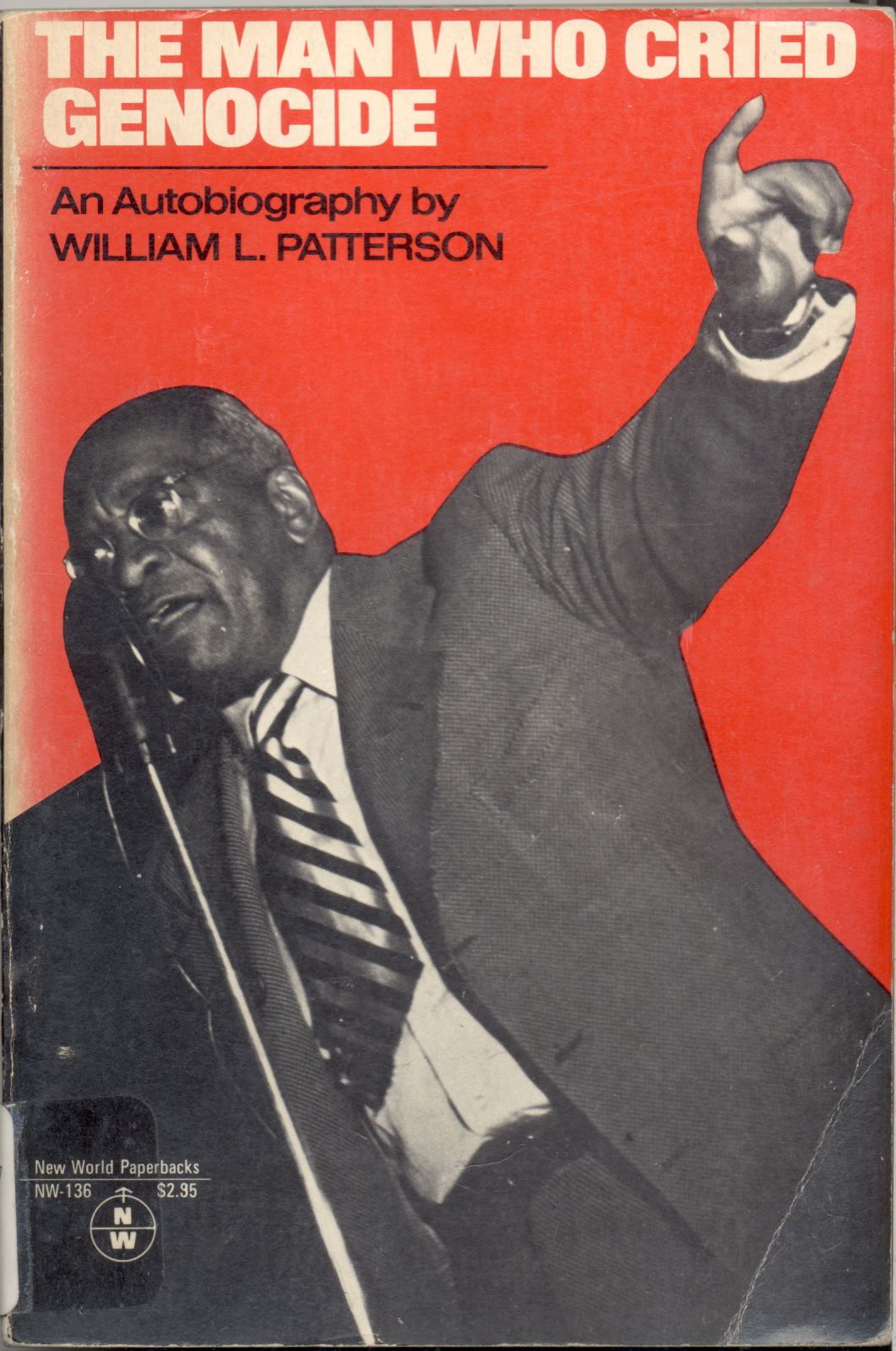

The CRC became increasingly isolated in this new climate as former allies refused to have anything to do with it. Represented by William Patterson and Paul Robeson, it attempted to file a petition entitled “We Charge Genocide” with the United Nations in 1949 that condemned the treatment of black citizens in the United States. Patterson was convicted a year later of violating the Smith Act; in 1954 the Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr. declared the CRC to be a subversive organization. The CRC received especially hostile attention from state authorities in the South, where it and related organizations were often raided or banned. The CRC dissolved in 1956, just as the civil rights movement in the South was about to become a mass movement.

At the same time the internal turmoil brought on by the Cold War, the Smith Act prosecutions, and the ouster of party leader Earl Browder, led to an internal battle. The Party expelled a number of members who were accused of displaying “white chauvinism”. In the grim days of 1949 and 1950, as the CP was about to be driven out of the CIO and much of the U.S. labor movement, many CPUSA leaders began to view their work among the white working class as a failure and the black working class as the “vanguard of the revolution”.

The Party directed those unions with CPUSA leadership to take a stance against continued use of seniority systems in those workplaces in which seniority made it more difficult for black workers to break out of segregated job classifications. It advocated “superseniority” for black workers, an early version of the type of measures that came to be known as “affirmative action” twenty years later. Many left-led unions, such as the UE, simply ignored the Party’s directive.

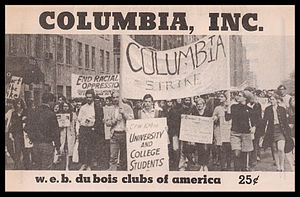

The Communist Party continued, even after splits and defections left it much smaller, into the 1960s. It made efforts to reestablish itself among students through the W. E. B. Du Bois Clubs, named after one of the original founders of the NAACP, who joined the CPUSA in 1961. Other youth organizations, such as the Che-Lumumba Club in Los Angeles, flourished for a time, then disappeared.

The parties’ fortunes appeared to revive for a while in the late 1960s, when party members such as Angela Davis became associated with the most militant wing of the Black Power movement. The party did not, however, reap any long-term benefits from this brief period of renewed exposure: it did not establish any lasting relations with the Black Panther Party, which was largely destroyed by the early 1970s by the FBI, and did not recruit any significant number of members from those organizations or win them to its politics.

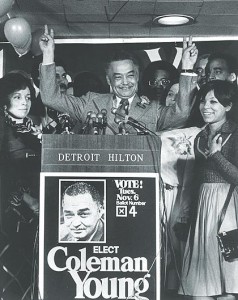

The party maintained some standing in the black community through its former allies, including Coleman Young of Detroit and Gus Newport in Berkeley, California, who were elected to office in the 1970s.