Welcome to the weekend BAYBAY!!

Our last film-worthy hustler of the week is a story we’ve heard before but is truly the best.

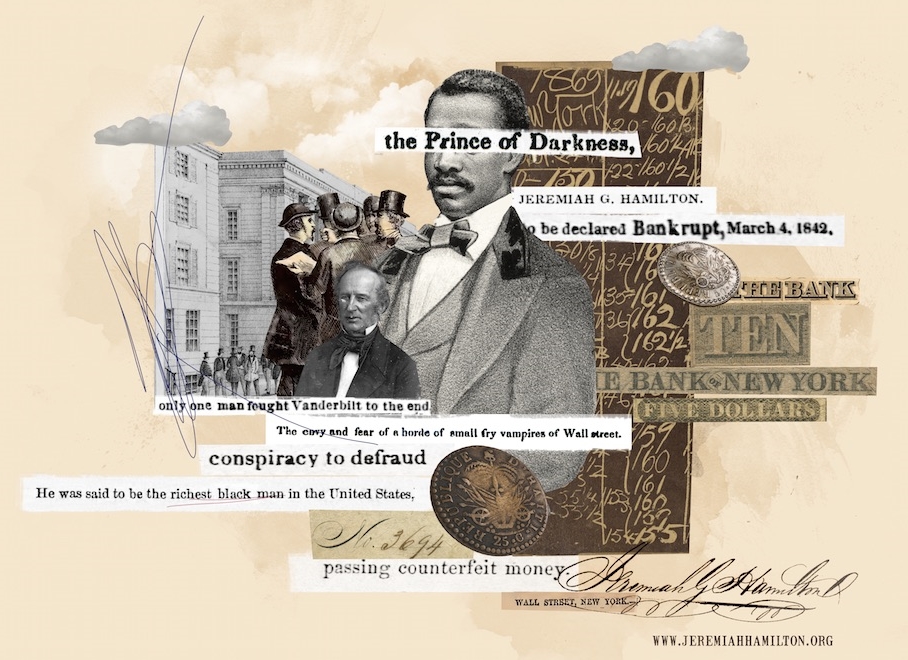

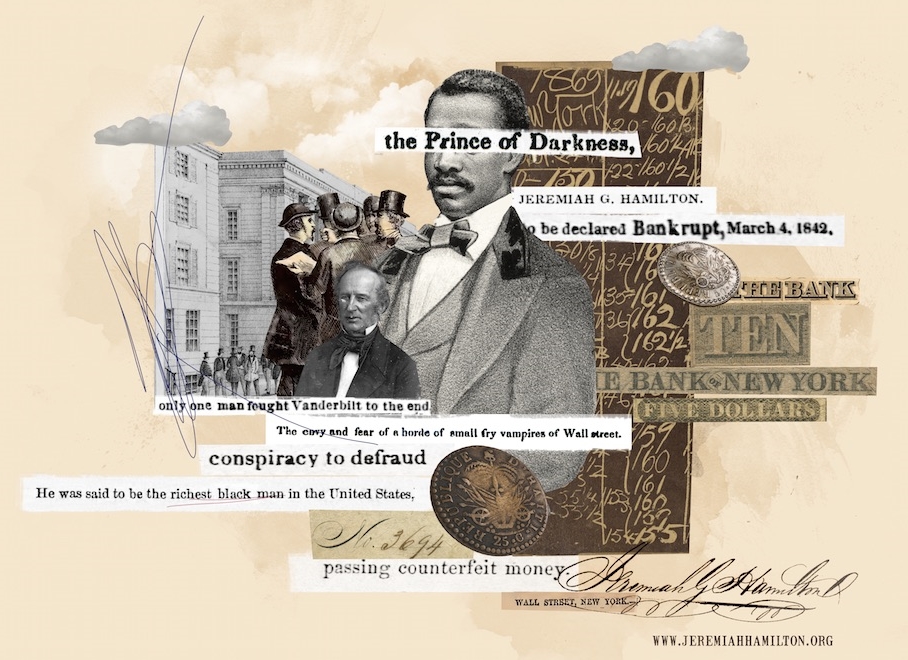

The Prince Of Darkness: Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire

He made white clients do his bidding. He bought insurance polices on ships he purposefully destroyed. And in 1875, died the richest black American.

Don’t you just love him already?

Jeremiah G. Hamilton (sometimes Jerry Hamilton) was a Wall Street broker noted as “the only black millionaire in New York” about a decade before the American Civil War. Hamilton was a shrewd financial agent, amassing a fortune of $2 million ($250 million today) by the time of his death in 1875. Although he was the subject of much newspaper coverage and his life provides a unique perspective on race in 19th century America, Hamilton is virtually absent from modern historical literature.

Hamilton first came to prominence in 1828 after hiding out in a fishing boat for multiple days in the Port-au-Prince harbor in Haiti and eventually escaping the Haitian authorities. They had discovered he was transporting counterfeit coins to Haiti reportedly for a group of New York merchants; in absentia he was sentenced to be shot. The ship he had chartered, the Ann Eliza Jane, was confiscated by the port officials; Hamilton claimed he had escaped with $5000 of the counterfeit coin.

Almost a decade later, after the 1835 Great Fire of New York destroyed most of the buildings on the southeast tip of Manhattan, Hamilton accrued about $5 million in 2013 dollars by “taking pitiless advantage of several of the fire victims’ misfortunes”. His business practices were controversial; where most black entrepreneurs sold their goods to other blacks, “Hamilton cut a swath through the lily-white New York business world of the mid-1830s, a domain where his depredations soon earned him the nickname of “The Prince of Darkness”. Others, with even less affection, simply called him “Nigger Hamilton”. Soon thereafter, he used about $7 million to buy up a substantial amount of land and property in modern-day Astoria and Poughkeepsie. Hamilton would go on to struggle with Cornelius Vanderbilt, the famous American industrialist, over control of the Nicaragua Transit Company.

Hamilton was a racist’s nightmare, an affront to the beliefs of most white New Yorkers. He was wealthy, successful, associated with whites – and married to a white woman. Eliza Jane Morris became pregnant with Hamilton’s child when she was just 13 or 14 and he was at least twice her age. They had nine more children, and their marriage lasted for some 40 years, until Hamilton’s death.

The Civil War merely heightened the absurdity of the black broker’s existence. On Wall Street, he carried on accumulating money, caring nothing about whom he upset. A master at manipulating speculative share values to his advantage, Hamilton saddled the client with any losses but pocketed any profits – a habit that often landed him in court. He gave scant, if any, thought to moderating his behavior or lifestyle. On one occasion in 1864, he imperiously suggested that boxes of expensive champagne and cigars were an ideal way for a white client to show his appreciation.

In 1845, the New Board, a secondary New York stock exchange, resolved to expel any member who bought or sold shares for him. One newspaper editor suggested the reason: “Hamilton is a colored man; and so, forsooth, his money is not to be received in the same ‘till’ with theirs. Oh, ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave.’”

Yet most brokers and merchants were more interested in the color of the black man’s money than his skin. Regardless, Hamilton simply brushed aside the obstacles placed in his way, or connived to get around them, and carried on amassing his fortune.

Hamilton did not shy away from physical confrontation with his enemies. In an 1843 court case, a witness, a prominent judge, viciously denigrated Hamilton’s character. Unable to restrain himself, Hamilton stood up in court and denounced him as an unreliable witness. Outside the chamber, the pair continued to quarrel, jostling and then brawling: when the judge struck Hamilton with his cane, the broker attempted to clobber him with a rung seized from a passing cart. The press had a field day.

In the 1850s, Hamilton would take on Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of America’s wealthiest and most ruthless tycoons, over control of the Accessory Transit Company. “There was only one man who ever fought the Commodore to the end and that was Jeremiah Hamilton,” wrote an obituarist in the National Republican the day after Vanderbilt died in 1877. The writer neither explained who Hamilton was nor mentioned his skin color, noting only that although Vanderbilt did not fear him (he did not fear anyone), the Commodore nonetheless “respected him.”

Although he circulated among the financial elite and was himself very wealthy, Hamilton was also a victim of the racism against African-Americans so pervasive during his time. During the New York City draft riots in 1863, white men seeking to lynch Hamilton broke into his house, but were turned away with only liquor, cigars, and an old suit by his wife Eliza after she said her husband was not home.

At the time of his death in May 1875, Jeremiah Hamilton was said by obituaries to be the richest black man in the United States. On his death, one obituary damned him as “the notorious colored capitalist long identified with commercial enterprises in this city.” But other tributes were gentler, noting that he was “with one exception, the oldest Wall Street speculator” and emphasizing that “his judgment in banking was highly esteemed, and he was often consulted by prominent bankers.” Harper’s Bazaar described him as “an intelligent, gentlemanly man.” He was buried in his family lot in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, next to two of his daughters.

The 2015 biography “Prince of Darkness” by Shane White chronicles the life of Jeremiah G. Hamilton.