GOOD MORNING P.O.U.! We hope you’re enjoying your weekend!

We conclude our series on African-American Civil War Spies with…

MARY TOUVESTRE

(From Harriet Tubman, Secret Agent: How Daring Slaves and Free Blacks Spied for the Union During the Civil War Thomas B. Allan)

Soon after the war began, U.S. Navy warships started steaming along coasts from Virginia to Texas, trying to keep ships from entering or leaving Southern ports. The Confederates sent out their own warships to break the naval blockade, as such an operation is called. Also sailing to aid the South were privateers, daring private ship owners and captains whose ships carried cargoes of guns, ammunition, and other supplies, mostly from British ports. The North’s blockade was named the Anaconda Plan, after the snake that slowly strangles its prey.

The Anaconda Plan did more than send Union ships to Southern coasts. The plan became part of a war-winning Union strategy that drew Harriet Tubman to South Carolina as a secret agent. It also gave many other African Americans in the South a chance to work for the North.

One important Southern port was Norfolk, Virginia, a key naval and shipbuilding center. Mary Touvestre (aka Mary Louvestre), a freed slave, was a housekeeper in Norfolk. Her employer was an engineer who was working on an important project at the Norfolk Navy Yard.

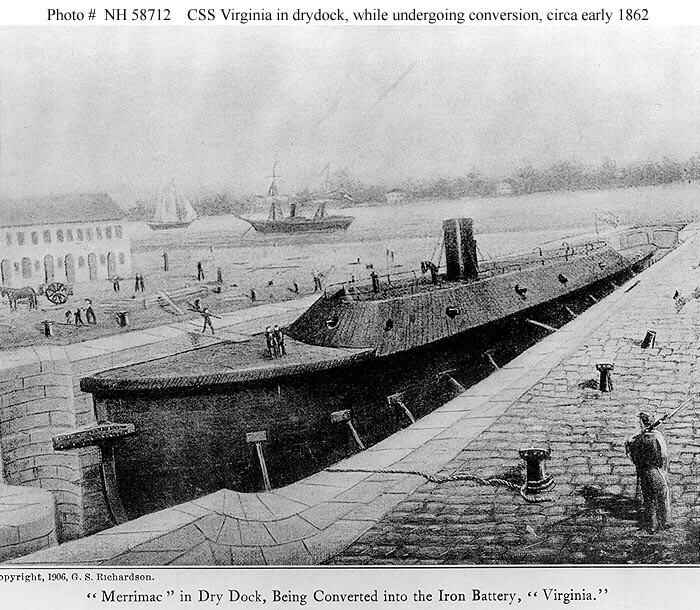

When Virginia seceded, Union forces had fled from Norfolk after setting fire to the Navy Yard and several ships,

including one called the Merrimack, which burned to the waterline and sank. Confederates raised the ship, renamed her Virginia, and started repairing her in secrecy.

That was the project that Mary Touvestre heard the engineer mention to his fellow workers. They talked when she was around because they considered her too ignorant to be able to understand what they were saying to each other.

But Mary realized that the men were building a new kind of ship — an ironclad warship that could destroy the wooden-hulled Union blockaders. Union cannonballs would bounce off Virginia‘s iron side, which were one to four inches thick. The Virginia also had an iron prow with and underwater ran designed to slam into and splinter the side of an enemy ship.

One day, the engineer brought home a set of plans. When Mary was alone, she stole the plans, hid them in her dress, and headed north to Washington. She carried a paper showing that she was a freed slave. But, at best, that would only get her to Confederate lines. She would have to risk her life to keep traveling on to Washington because word was spreading through the Confederacy that slaves were no longer to be trusted.

When Mary arrived in Washington, she managed to meet with Gideon Welles, Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy. In his office, he later wrote, she reported that “the ship was nearly finished, had come out of the dock, and was about receiving her armament.: To prove her story, she handed Welles the plans and other documents she had carried from Norfolk.

Welles, surprised by Mary’s report, speeded up the building of the Union’s own ironclad, the Monitor. Before the Monitor could reach Norfolk, the Virginia sank two Union blockade ships and damaged a third. But the Monitor arrived in time to attack the Virginia.

If Mary Touvestre had not told Welles about the Virginia, a historian wrote, “the Virginia could have had several more unchallenged weeks to destroy Union ships — setting back the Anaconda Plan by opening Norfolk to blockade runners that were carrying urgently needed supplies.”