Happy Saturday POU!

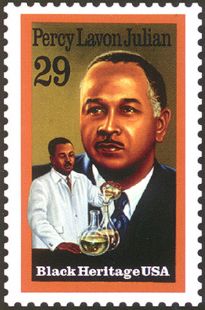

Percy Lavon Julian (April 11, 1899 – April 19, 1975) was an African American research chemist and a pioneer in the chemical synthesis of medicinal drugs from plants. He was the first to synthesize the natural product physostigmine, and a pioneer in the industrial large-scale chemical synthesis of the human hormones progesterone and testosterone from plant sterols such as stigmasterol and sitosterol. His work laid the foundation for the steroid drug industry’s production of cortisone, other corticosteroids, and birth control pills.

He later started his own company to synthesize steroid intermediates from the wild Mexican yam. His work helped greatly reduce the cost of steroid intermediates to large multinational pharmaceutical companies, helping to significantly expand the use of several important drugs.

Julian received more than 130 chemical patents. He was one of the first African Americans to receive a doctorate in chemistry. He was the first African-American chemist inducted into the National Academy of Sciences, and the second African-American scientist inducted (behind David Blackwell) from any field.

Percy Lavon Julian was born in Montgomery, Alabama, as the first child of six born to James Sumner Julian and Elizabeth Lena Julian, née Adams. Both of his parents were graduates of what was to be Alabama State University. His father, James, whose own father had been a slave, was employed as a clerk in the Railway Service of the United States Post Office, while his mother, Elizabeth, worked as a schoolteacher. Percy Julian grew up in the time of racist Jim Crow culture and legal regime in the southern United States. Among his childhood memories was finding a lynched man hanged from a tree while walking in the woods near his home. At a time when access to an education beyond the eighth grade was extremely rare for African-Americans, Julian’s parents steered all of their children toward higher education.

Julian attended DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. The college accepted few African-American students. The segregated nature of the town forced social humiliations. Julian was not allowed to live in the college dormitories and first stayed in an off-campus boarding home, which refused to serve him meals. It took him days before Julian found an establishment where he could eat. He later found work firing the furnace, waiting tables, and doing other odd jobs in a fraternity house; in return, he was allowed to sleep in the attic and eat at the house. Julian graduated from DePauw in 1920 as a Phi Beta Kappa and valedictorian. By 1930 Julian’s father would move the entire family to Greencastle so that all his children could attend college at DePauw. He still worked as a railroad postal clerk.

After graduating from DePauw, Julian wanted to obtain his doctorate in chemistry, but learned it would be difficult for an African-American to do so. Instead he obtained a position as a chemistry instructor at Fisk University. In 1923 he received an Austin Fellowship in Chemistry, which allowed him to attend Harvard University to obtain his M.S. However, worried that Euro-American students would resent being taught by an African-American, Harvard withdrew Julian’s teaching assistantship, making it impossible for him to complete his Ph.D. at Harvard.

In 1929, while an instructor at Howard University, Julian received a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship to continue his graduate work at the University of Vienna, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1931. He studied under Ernst Späth and was considered an impressive student. In Europe, he found freedom from the racial prejudices that had stifled him in the States. He freely participated in intellectual social gatherings, went to the opera and found greater acceptance among his peers. Julian was one of the first African Americans to receive a Ph.D. in chemistry, after St. Elmo Brady and Dr. Edward M.A. Chandler.

After returning from Vienna, Julian taught for one year at Howard University. At Howard, in part due to his position as a department head, Julian became caught up in university politics, setting off an embarrassing chain of events. At university president Mordecai Wyatt Johnson‘s request, he goaded white Professor of chemistry, Jacob Shohan (Ph.D from Harvard), into resigning. In late May 1932, Shohan retaliated by releasing to the local African-American newspaper the letters Julian had written to him from Vienna. The letters described “a variety of subjects from wine, pretty Viennese women, music and dances, to chemical experiments and plans for the new chemical building.” In the letters, he spoke with familiarity, and with some derision, of specific members of the Howard University faculty, terming one well-known Dean, an “ass”.

Around this same time, Julian also became entangled in an interpersonal conflict with his laboratory assistant, Robert Thompson. Julian had recommended Thompson for dismissal in March 1932. Thompson sued Julian for “alienating the affections of his wife”, Anna Roselle Thompson, stating he had seen them together in a sexual tryst. Julian counter-sued him for libel. When Thompson was fired, he too gave the paper intimate and personal letters which Julian had written to him from Vienna. Dr. Julian’s letters revealed “how he fooled the [Howard] president into accepting his plans for the chemistry building” and “how he bluffed his good friend into appointing” a professor of Julian’s liking. Through the summer of 1932, the Baltimore Afro-American published all of Julian’s letters. Eventually, the scandal and accompanying pressure forced Julian to resign. He lost his position and everything he had worked for.

Some happiness for Dr. Julian, however, was to come from this scandal. On December 24, 1935 he married Anna Roselle (Ph.D. in Sociology, 1937, University of Pennsylvania). They had two children: Percy Lavon Julian, Jr. (August 31, 1940 – February 24, 2008), who became a noted civil rights lawyer in Madison, Wisconsin; and Faith Roselle Julian (1944– ), who still resides in their Oak Park home and often makes inspirational speeches about her father and his contributions to science.

At the lowest point in Julian’s career, his former mentor, William Blanchard, threw him a much-needed lifeline. Blanchard offered Julian a position to teach organic chemistry at DePauw University in 1932. Julian then helped Josef Pikl, a fellow student at the University of Vienna, to come to the United States to work with him at DePauw. In 1935 Julian and Pikl completed the total synthesis of physostigmine and confirmed the structural formula assigned to it. Robert Robinson of Oxford University in the U.K. had been the first to publish a synthesis of physostigmine, but Julian noticed that the melting point of Robinson’s end product was wrong, indicating that he had not created it. When Julian completed his synthesis, the melting point matched the correct one for natural physostigmine from the calabar bean.

Julian also extracted stigmasterol, which took its name from Physostigma venenosum, the west African calabar bean that he hoped could serve as raw material for synthesis of human steroidal hormones. At about this time, in 1934, Butenandt and Fernholz, in Germany, had shown that stigmasterol, isolated from soybean oil, could be converted to progesterone by synthetic organic chemistry.

Circa 1950, Julian moved his family to the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, becoming the first African-American family to reside there. Although some residents welcomed them into the community, there was also opposition. Before they even moved in, on Thanksgiving Day, 1950, their home was fire-bombed. Later, after they moved in, the house was attacked with dynamite on June 12, 1951. The attacks galvanized the community, and a community group was formed to support the Julians. Julian’s son later recounted that during these times, he and his father often kept watch over the family’s property by sitting in a tree with a shotgun.

In 1953, Julian founded his own research firm, Julian Laboratories, Inc. He brought many of his best chemists, including African-Americans and women, from Glidden to his own company. Julian won a contract to provide Upjohn with $2 million worth of progesterone (equivalent to $16 million today). To compete against Syntex, he would have to use the same Mexican yam Mexican barbasco trade as his starting material. Julian used his own money and borrowed from friends to build a processing plant in Mexico, but he could not get a permit from the government to harvest the yams. Abraham Zlotnik, a former Jewish University of Vienna classmate whom Julian had helped escape from the Nazi European holocaust, led a search to find a new source of the yam in Guatemala for the company.

In July 1956, Julian and executives of two other American companies trying to enter the Mexican steroid intermediates market appeared before a U.S. Senate subcommittee. They testified that Syntex was using undue influence to monopolize access to the Mexican yam. The hearings resulted in Syntex signing a consent decree with the U.S. Justice Department. While it did not admit to restraining trade, it promised not to do so in the future. Within five years, large American multinationalpharmaceutical companies had acquired all six producers of steroid intermediates in Mexico, four of which had been Mexican-owned.

Read the entire story of this fascinating chemist here.