Happy Saturday POU!

Of course we could not leave out one of the most pivotal moments in Olympic history: The Black Power Salute

America was going through a cultural revolution in the 1960s, and one of the defining moments during that decade was the “Black Power Salute” in the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Mexico.

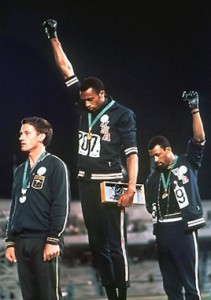

On Oct. 16, 1968, U.S. sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos (both from San Jose State University) placed first and third in the 200-meter sprint, respectively. Australian sprinter Peter Norman finished second.

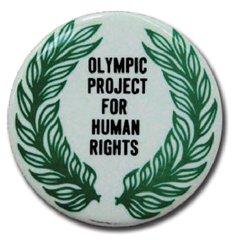

When the medal ceremony commenced, all three athletes wore Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badges, which protested racial segregation in all countries. Both Smith (1944-present) and Carlos (1945-present) were shoeless and wore black to represent black poverty.

A black scarf adorned Smith’s neck to symbolize black pride. Carlos unzipped his tracksuit top to demonstrate unity with all American blue-collar workers and wore a beaded necklace to remember lynched and murdered blacks.

Smith forgot his black gloves, but Norman suggested that Carlos share his with Smith. Smith raise his left fist while Carlos raised his right fist, a variation of the right-fist Black Power Salute during the national anthem.

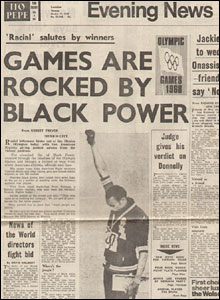

This action was printed in newspapers around the world and stirred much controversy. The International Olympic Committee president, Avery Brundage (a Nazi sympathizer who allowed Nazi salutes at the 1936 Games), banned Smith and Carlos from the games because he felt their domestic political statement was inappropriate for the Olympics’ apolitical stance.

22nd October 1968: Olympic medal winning, Afro-American atheletes for the 400 meters (from left to right) Lee Evans (gold), Larry James (silver), and Ron Freeman (bronze). The three wear black berets in sympathy for their suspended compatriots Tommie Smith & John Carlos who controversially gave the Black Power salute as the American national anthem was played during the medal ceremony for the 200 meters.

Anticipating some kind of protest was afoot, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had sent Jesse Owens to talk them out of it. (Owens’s four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin themselves held great symbolic significance, given Hitler’s belief in Aryan supremacy.) Carlos’s mind was made up. When he and Smith struck their pose, Carlos feared the worst. Look at the picture and you’ll see that while Smith’s arm is raised long and erect, Carlos has his slightly bent at the elbow. “I wanted to make sure, in case someone rushed us, I could throw down a hammer punch,” he writes. “We had just received so many threats leading up to that point, I refused to be defenseless at that moment of truth.”

It was also a moment of silence. “You could have heard a frog piss on cotton. There’s something awful about hearing 50,000 people go silent, like being in the eye of a hurricane.”

And then came the storm. First boos. Then insults and worse. People throwing things and screaming racist abuse. “Niggers need to go back to Africa!” and, “I can’t believe this is how you niggers treat us after we let you run in our games.”

The sight of two black athletes in open rebellion on the international stage sent a message to both America and the world. At home, this brazen disdain for the tropes of American patriotism – flag and anthem – shifted dissidence from the periphery of American life to primetime television in a single gesture, while revealing what DuBois once termed the “essential two-ness” of the black American condition. “An American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Globally, it was understood as an act of solidarity with all those fighting for greater equality, justice and human rights. Margaret Lambert, a Jewish high jumper who was forced, for show, to try out for the 1936 German Olympic team, even though she knew she would never be allowed to compete, said how delighted it made her feel. “When I saw those two guys with their fists up on the victory stand, it made my heart jump. It was beautiful.”

Smith and Carlos were immediately ostracized by the U.S. sporting establishment and they were subject to criticism. Time magazine showed the five-ring Olympic logo with the words, “Angrier, Nastier, Uglier”, instead of “Faster, Higher, Stronger”. Back home, they were subject to abuse and they and their families received death threats.

Smith and Carlos’ actions eventually helped remove Brundage as the IOC president, achieving one of OPHR’s main goals. However, the toll from their simple act of protesting the conditions of people of color would effect their lives forever.

Smith continued in athletics, playing in the NFL with the Cincinnati Bengals before becoming an assistant professor of physical education at Oberlin College. In 1995, he helped coach the U.S. team at the World Indoor Championships at Barelona. In 1999 he was awarded the California Black Sportsman of the Millennium Award. He is now a public speaker.

Carlos’ career followed a similar path. He tied the 100 yard dash world record the following year. He later played in the NFL with the Philadelphia Eagles until a knee injury prematurely ended his career. He fell upon hard times in the late 1970s. In 1977, his ex-wife committed suicide, leading him to a period of depression. In 1982, Carlos was employed by the Organizing Committee for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles to promote the games and act as liaison with the city’s black community. In 1985, he became a track and field coach at Palm Springs High School, where he still remains as a counselor.

Smith and Carlos received the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the 2008 ESPY Awards honoring their action.

Few know that the Australian sprinter Peter Norman who shocked everyone by powering past Carlos and winning the silver medal, played his own, crucial role in sporting history.

On his left breast he wore a small badge that read: “Olympic Project for Human Rights” — an organization set up a year previously opposed to racism in sport. While Smith and Carlos are now feted as human rights pioneers, the badge was enough to effectively end Norman’s career. He returned home to Australia a pariah, suffering unofficial sanction and ridicule as the Black Power salute’s forgotten man. He never ran in the Olympics again.

“As soon as he got home he was hated,” explains his nephew Matthew Norman, who has directed a new film — “Salute!” — about Peter’s life before and after the 1968 Olympics.

“A lot of people in America didn’t realize that Peter had a much bigger role to play. He was fifth (fastest) in the world, and his run is still a Commonwealth record today. And yet he didn’t go to Munich (1972 Olympics) because he played up. He would have won a gold.

“He suffered to the day he died.”

Smith and Carlos had already decided to make a statement on the podium. They were to wear black gloves. But Carlos left his at the Olympic village. It was Norman who suggested they should wear one each on alternate hands. Yet Norman had no means of making a protest of his own. So he asked a member of the U.S. rowing team for his “Olympic Project for Human Rights” badge, so that he could show solidarity.

“He came up to me and said, ‘Have you got one of those buttons, mate,’ ” said U.S. rower Paul Hoffman. “If a white Australian is going to ask me for an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, then by God he would have one. I only had one, which was mine, so I took it off and gave it to him.”

Norman retired from athletics immediately after hearing he’d been cut from the Munich team. He would never return to the track. Neither would his achievements count for much 28 years later when Sydney hosted the 2000 Olympics.

“At the Sydney Olympics he wasn’t invited in any capacity,” says Matthew Norman.

“There was no outcry. He was the greatest Olympic sprinter in our history.”

In his own country Peter Norman remained the forgotten man. As soon as the U.S. delegation discovered that Norman wasn’t going to attend, the United States Olympic Committee arranged to fly him to Sydney to be part of their delegation. He was invited to the birthday party of 200 and 400-meter runner Michael Johnson, where he was to be the guest of honor. Johnson took his hand, hugged him and declared that Norman was one of his biggest heroes.

Norman died in 2006. Smith and Carlos served as pallbearers at his funeral.

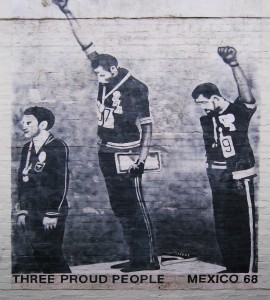

A mural depicting the three protesting athletes stands to this day in Newton, Australia.