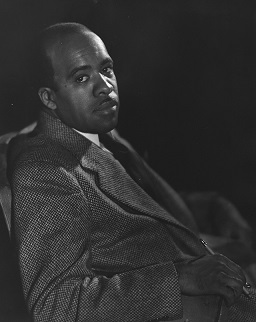

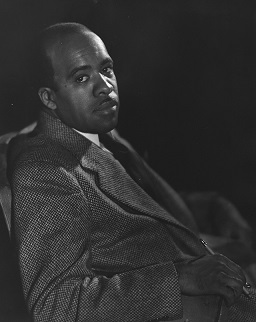

It took LeRoy Winbush 11 years to become the first black member of the Art Directors Club of Chicago, but once the organization accepted him, only five years to become its president.

Winbush moved to Chicago from Detroit as a teenager and became a graphic designer there in 1936, one week after he graduated from high school. At the time, the profession had only a few black practitioners, one of whom—Charles Dawson—had numerous clients on Chicago’s South Side. Winbush started out in the same community, but his role models were South Side sign painters.

He jumped from an apprenticeship in a sign shop to a job designing signage, murals and flyers for the Regal Theater, where he “rubbed shoulders” with performers such as Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, according to Lockhart. Music was an important influence on Winbush’s career as well as a beloved hobby: as a teenager, he performed at Chicago’s Century of Progress exposition with his band the Melody Mixers, and he later designed album covers for the Ramsey Lewis Trio and other groups signed to Mercury Records.

Yet unlike Dawson, Winbush worked for a diverse range of clients at a time when racism seemed to be an insurmountable barrier. After leaving the Regal Theater, he joined the sign shop at Goldblatt’s, a local department store chain where he was the only black employee. By the time he left seven years later, he was the art director for all the Goldblatt’s stores, creating merchandising displays and managing a staff of 60 people.

He had also become an accomplished airbrush illustrator. Winbush founded his own firm, Winbush Associates (later Winbush Design), on the South Side in 1945. Every morning, he spent three hours working as the art director for the Consolidated Manufacturing Company. Every afternoon, he spent three hours working as the art director for Johnson Publishing, designing layouts for magazines including Ebony and Jet.

A 1958 Ebony article profiling Winbush—entitled “The Barnum of Bankers Row”—indicates how successful his business model was. Winbush “excelled at exhibit design,” according to Margolin, and he convinced a bank in the heart of Chicago’s financial district to hire him to create window displays. Such things were unheard of in banking at the time, but Winbush Associates soon cornered the market its principal had invented, devising elaborate narrative displays with mannequins and props for 62 clients in the financial industry.

When enthusiasm for this form of advertising waned among the banks, Winbush found other outlets for his expertise in exhibit design. In 1959, he served as chairman of exhibits for the International Design Conference at Aspen, which he was closely involved with for eight years. Winbush also helped design Illinois’s exhibit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair—including its animatronic Abraham Lincoln, which was the prototype for the figures in the Hall of Presidents at Disney World.

A few years later, Winbush began teaching visual communications at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and typography at Columbia College Chicago.

Although Winbush insisted that he wanted to be known as a “good designer,” not a “black designer,” he “believed he could use design as a tool to help the black community,” says Lockhart. He developed a long-term exhibition about sickle-cell anemia for the city’s Museum of Science and Industry and in 1990 became an exhibition consultant to the DuSable Museum of African-American History, the first museum of its kind. Winbush continued designing exhibitions for the DuSable on subjects such as the Underground Railroad and the uprising on the slave ship Amistad until he was well into his 80s.

“He was a real pioneer for my generation,” Lockhart concludes. “Seeing Winbush let us know that a career in design was possible.”