This week’s open threads gave some detailed background on several black history facts. On this last day of Black History Month, I am going to highlight a current NFL player’s ancestor’s fight against slavery.

When all else failed, black mobs sometimes prevented the capture of fugitives

As kidnappers captured free and fugitive Northern blacks, intent on enslaving them, some black communities resisted. To prevent the seizure, they mobbed the courthouses where the cases of the fugitive or the free blacks were tried.

Blacks in Boston did it. And in a small Ohio town, blacks rescued a fugitive from the clutches of kidnappers. A minister who participated described the kidnapping and rescue:

“While engaged in his daily avocation, by which he made an honest and respectable living for his family, three men came suddenly upon him, put a rope around his neck and unceremoniously dragged him beyond the limits of the Town authorities and on to his former place of slavery.

“The news spread, almost with lightning speed through the colored community. We rallied 200 strong in little or no time. Men and women were much excited, some of the latter consoling the bereaved wife and children, others following the accumulating multitude. We came upon these man stealers three miles from the town. One end of the rope was connected to the neck of a horse, and the fugitive was walking or running, while the men were riding.

“The advancing crowd raised a shout. The slave looked behind and motioned his hand for them to hasten their speed. When it became apparent to [the slave catchers] that their own liberty and security were in danger, they cut the rope from the neck of the steed and spurring their horses were soon out of sight. The fugitive was borne back on the shoulders of his friends, with triumphant shouts, “A man saved from Slavery!”” – William Mitchell

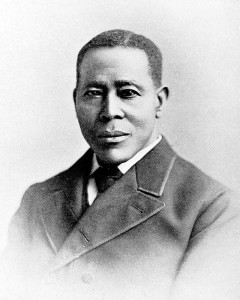

William Still (October 7, 1821 – July 14, 1902) was an African-American abolitionist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, conductor on the Underground Railroad, writer, historian and civil rights activist. He was chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He directly aided fugitive slaves and kept records of their lives, to help families reunite after slavery was abolished. After the American Civil War, he wrote an account of the underground system and the experiences of many refugee slaves, entitled The Underground Railroad Records, published in 1872.

William Still was born October 7, 1821 (or November 1819) in Burlington County, New Jersey, to Sidney (later renamed Charity) and Levin Still. His parents had come to New Jersey separately. First, his father bought his freedom in 1798 from his master inCaroline County, Maryland on the Eastern Shore. Charity escaped twice from Maryland. The first time, she escaped with their four children. They were all recaptured and returned to slavery. A few months later, Charity escaped again, taking only her two younger daughters with her. She succeeded in reaching her husband in New Jersey. Following her escape, Charity and Levin had 14 more children, of whom William was the youngest. Though these children were born in the free state of New Jersey, under Maryland and federal slave law, they were still legally slaves, as their mother was an escaped slave. According to New Jersey law, they were free. Charity and Levin could do nothing for their older boys left in slavery.

Levin, Jr. and Peter Still were sold from Maryland to slaveowners in Lexington, Kentucky. Later they were resold to planters in Alabama in the Deep South. Levin, Jr. died from a whipping while enslaved. Peter and most of his family escaped from slavery when he was about age 50, with the help of two brothers named Friedman, who operated mercantile establishments in Florence, Alabama and Cincinnati, Ohio. Kate E. R. Pickard wrote about Peter Still and his family in her book, The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: Recollections of Peter Still and his Wife “Vina,” After Forty Years of Slavery (1856).

After reaching Philadelphia, Peter sought help at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society to find his parents or other members of his birth family. When they first met, he and William Still had no idea they were related. But, as William listened to Peter’s story, he recognized the history his mother had told him many times. After learning that his older brother Levin was whipped to death for visiting his wife without permission, William shouted, “What if I told you I was your brother!” Later Peter and his mother were reunited after having been separated for 42 years.

Another of William’s brothers was James Still. Born in New Jersey in 1812, James wanted to become a doctor but said he “was not the right color to enter where such knowledge was dispensed.” James studied herbs and plants and apprenticed himself to a white doctor to learn medicine. He became known as the “Black Doctor of the Pines”, as he lived and practiced in the Pine Barrens. James’ son, James Thomas Still, completed his dream, graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1871.

Brothers Peter, James and William Still later moved with their families to Lawnside, New Jersey, a town developed and owned by African Americans. To this day, their descendants have an annual family reunion every August. Notable members of the Still family include the composer William Grant Still, professional WNBA basketball player Valerie Still, professional NFL defensive end Art Still, and professional NFL defensive tackle Devon Still.

William’s other siblings included Levin, Jr.; Peter; James; Samuel; Mary, a teacher and missionary in the African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mahala (who married Gabriel Thompson); and Kitturah, who moved to Pennsylvania.

In 1844, William Still moved from New Jersey to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1847, he married Letitia George. William and Letitia had four children who survived infancy. Their oldest was Caroline Matilda Still (1848–1919), a pioneer female medical doctor. Caroline attended Oberlin College and the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia (much later known as the Medical College of Pennsylvania). She married Edward J. Wyley and, after his death, the Reverend Matthew Anderson, longtime pastor of the Berean Presbyterian Church in North Philadelphia. She had an extensive private medical practice in Philadelphia and was also a community activist, teacher and leader.

William Wilberforce Still (1854–1914) graduated from Lincoln University and subsequently practiced law in Philadelphia. Robert George Still (1861–1896) became a journalist and owned a print shop on Pine at 11th Street in central Philadelphia. Frances Ellen Still (1857–1930) became a kindergarten teacher (she was named after poet Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who had lived with the Stills before her marriage). According to the 1900 U.S. Census, William W., his wife, and Frances Ellen were living in the household of the elderly William Still and his wife. It was customary for extended family to live together.

In 1847, three years after settling in Philadelphia, Still began working as a clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. When Philadelphia abolitionists organized a Vigilance Committee to directly aid escaped slaves who had reached the city, Still became its chairman. By the 1850’s, Still was one of the leaders of Philadelphia’s African-American community.

In 1855, he participated in the nationally covered rescue of Jane Johnson, a slave who sought help from the Society in gaining freedom while passing through Philadelphia with her master John Hill Wheeler, newly appointed US Minister to Nicaragua. Still and others liberated her and her two sons under Pennsylvania law, which held that slaves brought to the free state voluntarily by a slaveholder could choose freedom. Her master sued him and five other African Americans for assault and kidnapping in a high-profile case in August 1855. Jane Johnson returned to Philadelphia from New York and testified in court as to her independence in choosing freedom, winning acquittal for Still and four others, and reduced sentences for the last two.

In 1859, Still challenged the segregation of the city’s public transit system, which had separate seating for whites and blacks. He kept lobbying and, in 1865, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law to integrate streetcars across the state.

He opened a stove store during the American Civil War, and operated the post exchange at Camp William Penn, the training camp for United States Colored Troops north of Philadelphia. After the war, Still owned and operated a coal delivery business, eventually coming to own his own coal yard in 1861.

Often called “The Father of the Underground Railroad”, Still helped as many as 800 slaves escape to freedom. He interviewed each person and kept careful records, including a brief biography and the destination for each, along with any alias adopted. He kept his records carefully hidden but knew the accounts would be critical in aiding the future reunion of family members who became separated under slavery, which he had learned when he aided his own brother Peter, whom he had previously never met before.

Still worked with other Underground Railroad agents operating in the South and in many counties in southern Pennsylvania. His network to freedom also included agents in New Jersey, New York, New England and Canada. Conductor Harriet Tubman traveled through his office with fellow passengers on several occasions during the 1850s and Still forged a connection with the family of John Brown.

After the Civil War, Still published an account of the Underground Railroad, The Underground Railroad Records (1872), based on the secret notes he had kept in diaries during those years. His book has been integral to the history of these years, as he carefully recorded many details of the workings of the Underground Railroad. It went through three editions and in 1876 was displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

Still had a strong interest in the welfare of black youth. He helped to establish an orphanage and the first YMCA for African Americans in Philadelphia. He also attended national conventions such as the New England Colored Citizens’ Convention of 1859, where he advocated for equal educational opportunities for all African Americans.