The Ghetto Informant Program (GIP) was an intelligence-gathering operation run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1967–1973. Its official purpose was to collect information pertaining to riots and civil unrest. Through GIP, the FBI used more than 7000 people to infiltrate poor black communities in the United States.

The program was targeted at those likely to have information about “ghetto happenings”. Thus (according to an internal memo) it included people such as “the proprietor of a candy store or barber shop” in a ghetto area. These informants were “listening posts”—tools for blanket surveillance of a community or area. GIP operated with no oversight from courts or Congress.

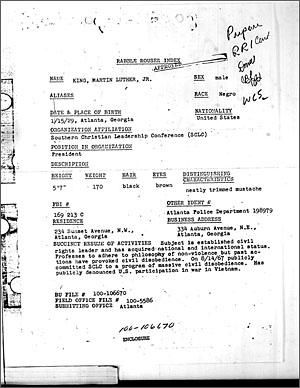

Informants monitored “Key Black Extremists” (or rather ANY black leader or activist) such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Floyd McKissick, Huey Newton, and more. One of the first major projects involving the GIP was Operation POCAM, the FBI’s effort to monitor and disrupt the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. Informants were later asked to report on Afro-American bookstores and investigate the existence of subversive literature.

In 1967, as part of GIP, the FBI also established various databases to distinguish those it spied on: the“Agitator Index,” the “Rabble Rouser Index,” and the “Security Index.”

The FBI strove to monitor and disrupt the Poor People’s campaign in 1968, which it code-named “POCAM”. The FBI, which had been targeting King since 1962 with COINTELPRO, increased its efforts after King’s April 4, 1967 speech titled “Beyond Vietnam”. It also lobbied government officials to oppose King on the grounds that he was a communist, “an instrument in the hands of subversive forces seeking to undermine the nation”, and affiliated with “two of the most dedicated and dangerous communists in the country” (Stanley Levison and Harry Wachtel). After “Beyond Vietnam” these efforts were reportedly successful in turning lawmakers and administration officials against King, the SCLC, and the cause of civil rights. After King was assassinated and the marches got underway, reports began to emphasize the threat of black militancy instead of communism.

Operation POCAM became the first major project of the FBI’s Ghetto Informant Program (GIP), which recruited thousands of people to report on poor black communities. Through GIP, the FBI quickly established files on SCLC recruiters in cities across the US. FBI agents posed as journalists, used wiretaps, and even recruited some of the recruiters as informants.

The FBI sought to disrupt the campaign by spreading rumors that it was bankrupt, that it would not be safe, and that participants would lose welfare benefits upon returning home. Local bureaus reported particular success for intimidation campaigns in Birmingham Alabama, Savannah Georgia and Cleveland Ohio. In RIchmond, Virginia, the FBI collaborated with the John Birch Society to set up an organization called Truth About Civil Turmoil (TACT). TACT held events featuring a Black woman named Julia Brown who claimed to have infiltrated the civil rights movement and exposed its Communist leadership.

In one particularly controversial 1965 incident, white civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo was murdered by Ku Klux Klansmen, who gave chase and fired shots into her car after noticing that her passenger was a young black man; one of the Klansmen was Gary Thomas Rowe, an acknowledged FBI informant. The FBI spread rumors that Liuzzo was a member of the Communist Party and had abandoned her children to have sexual relationships with African Americans involved in the civil rights movement. FBI records show that J. Edgar Hoover personally communicated these insinuations to President Johnson.

The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States is a book by Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, first published in 1990. It is a history of the FBI’s COINTELPRO efforts to disrupt dissident political organizations within the United States, and reproduces many original FBI memos. The book is dedicated to Fred Hampton and Mark Clark