We take a final look at the efforts by former slaves to find their loved ones after being separated by the cruelties of slavery.

Washington, D.C., circa 1916. “Slaves reunion. Lewis Martin, age 100; Martha Elizabeth Banks, age 104; Amy Ware, age 103; Rev. Simon P. Drew, born free.” Cosmopolitan Baptist Church, 921 N Street N.W.

After emancipation, some African American families that were torn apart by slavery turned to newspaper ads in hopes of finding lost loved ones.

These “information wanted” advertisements primarily appeared in black-oriented newspapers, which sprang up after the end of the U.S. Civil War.

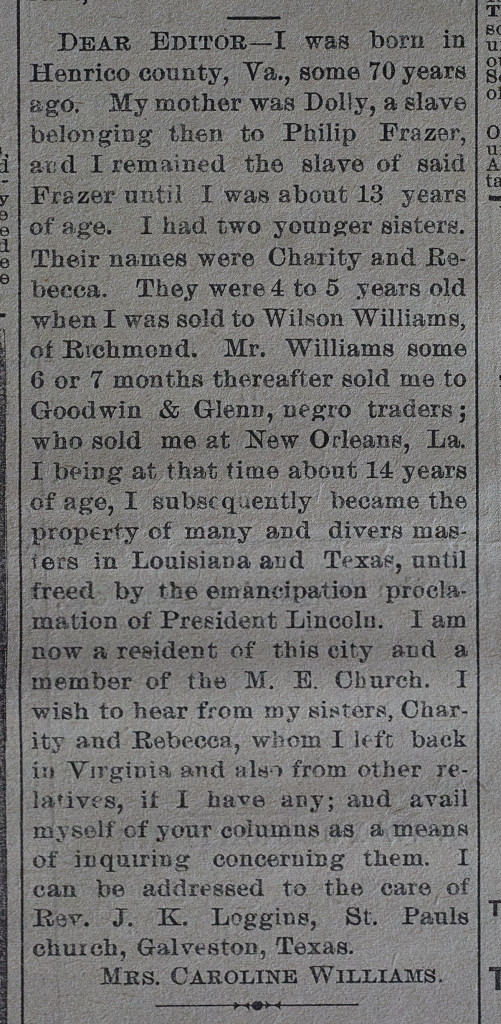

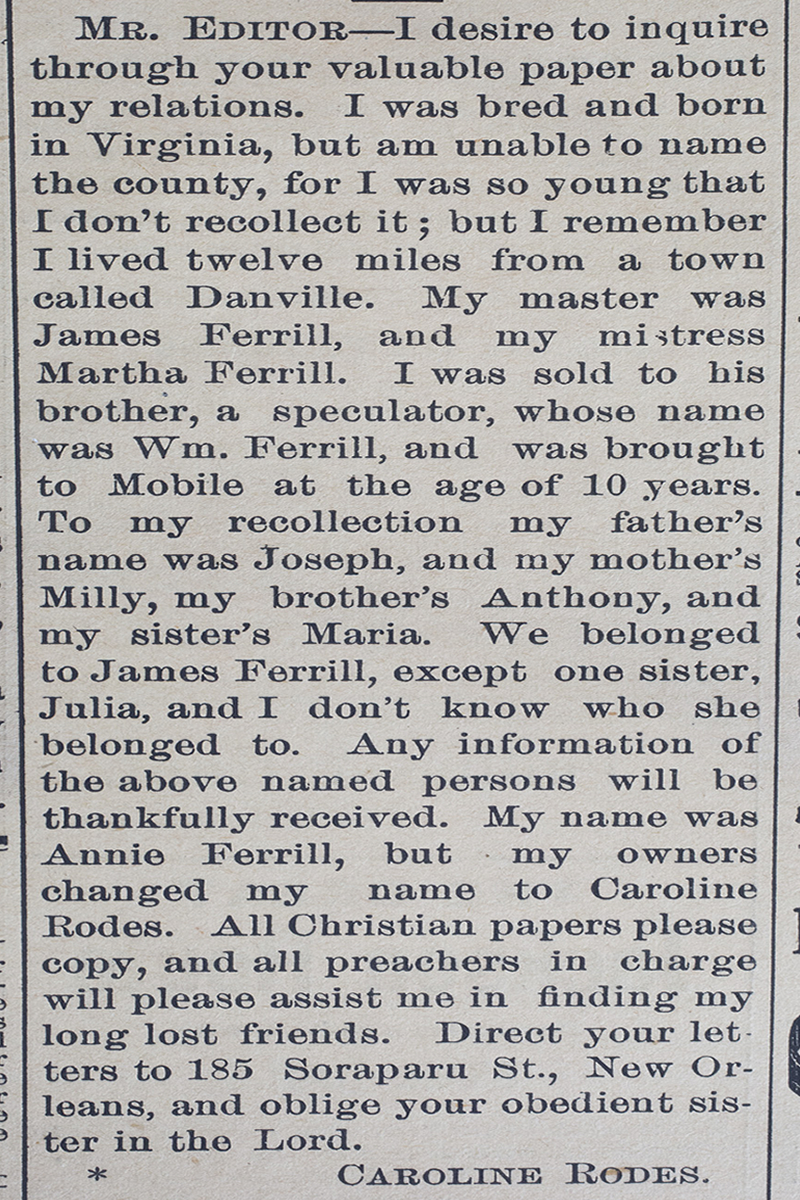

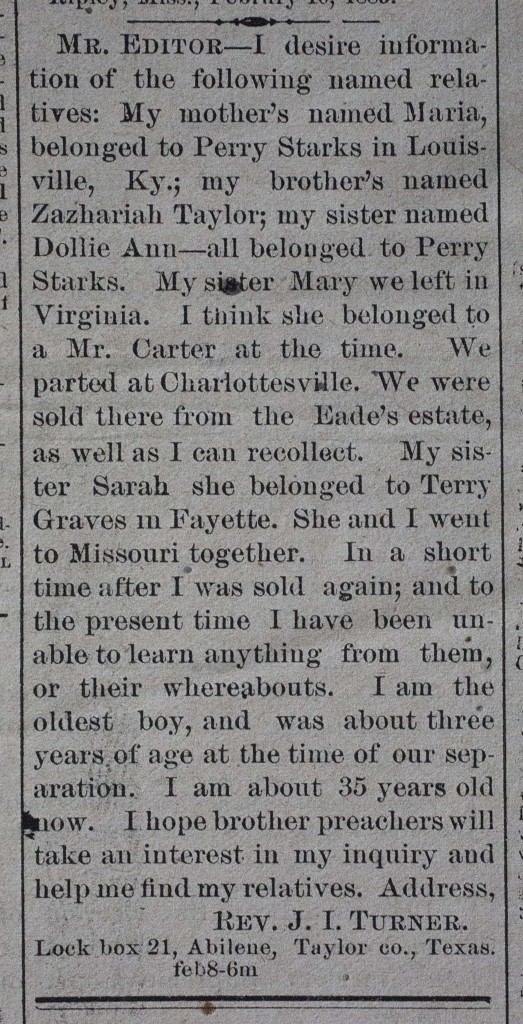

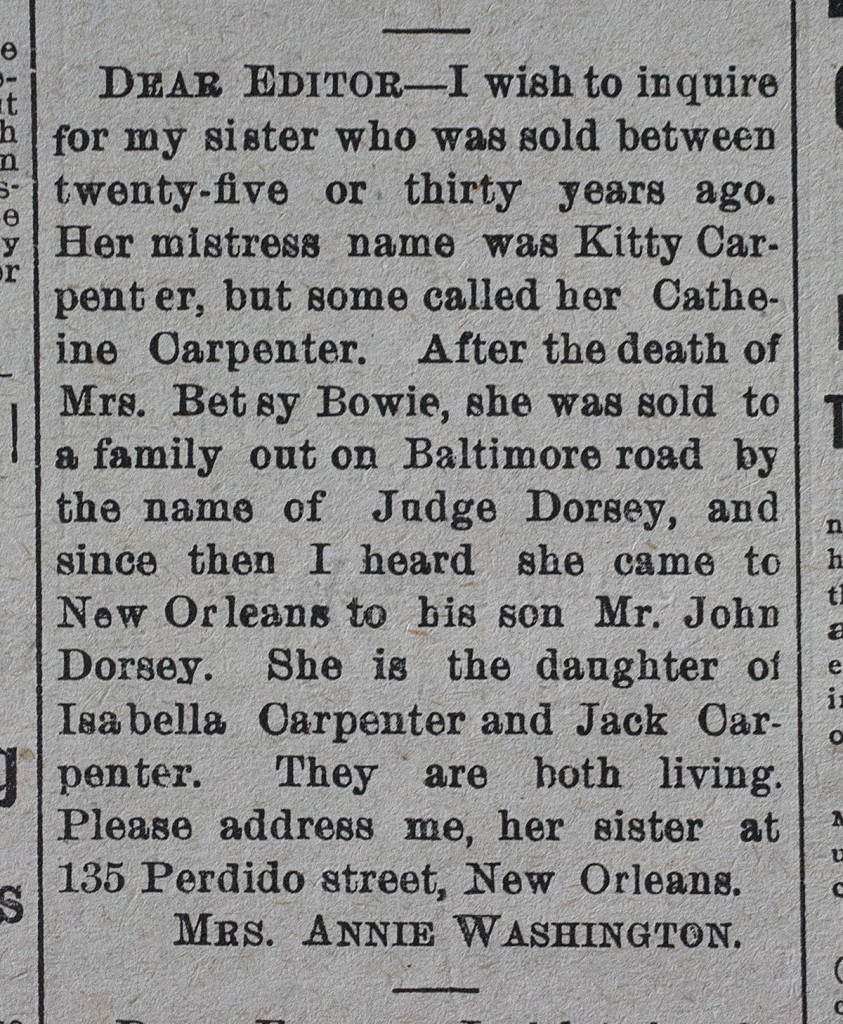

A series of “Lost Friends” ads that appeared in a New Orleans newspaper in the late 1800s into the early 1900s illustrate how desperate friends and relatives searched for loved ones who had been lost to slavery.

The Southwestern Christian Advocate was distributed to about 500 preachers, 800 post offices and 4,000 subscribers in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas. The newspaper started running its “Lost Friends” columns in 1877 and continued doing so “well into the first decade of the twentieth century.”

The advertisements cost 50 cents each, about one day’s wages, and pastors would read them aloud in church to help spread the word.

“At first, all I could see was grief…but then I started to see hope embedded in it,” said Heather Andrea Williams, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who wrote a book about the “information wanted” ads. “There’s a lot packed into these very short messages of love and grief and resilience and an ability…to continue to care.”

An online database shows more than 900 of these advertisements that appeared in the Southwestern Christian Advocate between November 1879 and March 1884. The digital images are courtesy of the Louisiana State University Libraries Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library.

The ads provide insight into the dark nature of slavery, with African-American families facing the ever-present possibility of being sold away from loved ones into unknown circumstances, having names changed by new “owners” and perhaps forever losing track of family members.

“I think these ads really take us into the structure of slavery, the power of owners and into the emotional lives of enslaved people,” said Williams. “You could be married and yet your owner could sell you…not everybody experienced separation but everybody could have experienced separation and they knew this. That this is looming.”

In her book, Help Me Find My People, Williams writes that one-third of enslaved children were separated from their parents by either being sold away or having their parents sold away. Reunions of these broken families were rare. However, when they did occur, reunited families faced difficult decisions and periods of readjustment.

There were situations where children didn’t remember their parents and had grown attached to another adult caretaker, or incidents where the spouse who’d been left behind remarried.

“A husband returns to a plantation after many years away because he had been sold away and his wife is now with somebody else,” Williams said, “and now she had to make a decision and sometimes the woman said, ‘The husband I’m with today knows that the reason we got together was because my real husband has gone away and I’m going back to my real husband.’”

There is no way to know how many formerly enslaved people found their loved ones, however the yearning to be reunited with lost family members lingered for decades. The “information wanted” newspaper ads continued to appear into the 1900s, more than 35 years after the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of all slaves in the United States.