Influence

Scott-Heron’s work has influenced writers, academics and musicians, from indie rockers to rappers. His work during the 1970’s influenced and helped engender subsequent African-American music genres, such as hip-hop and neo-soul. He has been described by music writers as “the godfather of rap” and “the black Bob Dylan.”

Chicago Tribune writer Greg Kot comments on Scott-Heron’s collaborative work with Jackson:

Together they crafted jazz-influenced soul and funk that brought new depth and political consciousness to ‘70’s music alongside Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. In classic albums such as ‘Winter in America‘ and ‘From South Africa to South Carolina,’ Scott-Heron took the news of the day and transformed it into social commentary, wicked satire, and proto-rap anthems. He updated his dispatches from the front lines of the inner city on tour, improvising lyrics with an improvisational daring that matched the jazz-soul swirl of the music”.

Whitey on the Moon

Of Scott-Heron’s influence on hip hop, Kot writes that he “presag[ed] hip-hop and infus[ed] soul and jazz with poetry, humor and pointed political commentary”. Ben Sisario ofThe New York Times writes that “He [Scott-Heron] preferred to call himself a “bluesologist,” drawing on the traditions of blues, jazz and Harlem renaissance poetics.” Tris McCallof The Star-Ledger writes that “The arrangements on Gil Scott-Heron’s early recordings were consistent with the conventions of jazz poetry – the movement that sought to bring the spontaneity of live performance to the reading of verse.” A music writer later noted that “Scott-Heron’s unique proto-rap style influenced a generation of hip-hop artists,”while The Washington Post wrote that “Scott-Heron’s work presaged not only conscious rap and poetry slams, but also acid jazz, particularly during his rewarding collaboration with composer-keyboardist-flutist Brian Jackson in the mid- and late ’70’s.” The Observer‘s Sean O’Hagan discussed the significance of Scott-Heron’s music with Brian Jackson, stating:

Together throughout the 1970’s, Scott-Heron and Jackson made music that reflected the turbulence, uncertainty and increasing pessimism of the times, merging the soul and jazz traditions and drawing on an oral poetry tradition that reached back to the blues and forward to hip-hop. The music sounded by turns angry, defiant and regretful while Scott-Heron’s lyrics possessed a satirical edge that set them apart from the militant soul of contemporaries such as Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield.

Will Layman of PopMatters wrote about the significance of Scott-Heron’s early musical work:

In the early 1970s, Gil Scott-Heron popped onto the scene as a soul poet with jazz leanings; not just another Bill Withers, but a political voice with a poet’s skill. His spoken-voice work had punch and topicality. ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ and ‘Johannesburg’ were calls to action: Stokely Carmichael if he’d had the groove of Ray Charles. ‘The Bottle’ was a poignant story of the streets: Richard Wright as sung by a husky-voiced Marvin Gaye. To paraphrase Chuck D, Gil Scott-Heron’s music was a kind of CNN for black neighborhoods, prefiguring hip-hop by several years. It grew from the Last Poets, but it also had the funky swing of Horace Silver or Herbie Hancock—or Otis Redding. Pieces of a Man and Winter in America (collaborations with Brian Jackson) were classics beyond category”.

Home is Where the Hatred Is

Scott-Heron’s influence over hip hop is primarily exemplified by his definitive single “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” sentiments from which have been explored by various rappers, including Aesop Rock, Talib Kweli and Common. In addition to his vocal style, Scott-Heron’s indirect contributions to rap music extend to his and co-producer Jackson’s compositions, which have been sampled by various hip hop artists. “We Almost Lost Detroit” was sampled by Brand Nubian member Grand Puba (“Keep On”), Native Tongues duo Black Star (“Brown Skin Lady”), and MF DOOM (“Camphor”). Additionally, Scott-Heron’s 1980 song “A Legend in His Own Mind” was sampled on Mos Def’s “Mr. Nigga,” the opening lyrics from his 1978 recording “Angel Dust” were appropriated by rapper RBX on the 1996 song “Blunt Time” by Dr. Dre, and CeCe Peniston’s 2000 song “My Boo” samples Scott-Heron’s 1974 recording “The Bottle”.

In addition to the Scott-Heron excerpt used in “Who Will Survive in America,” West sampled Scott-Heron and Jackson’s “Home is Where the Hatred Is” and “We Almost Lost Detroit” for the songs “My Way Home” and “The People,” respectively, both of which are collaborative efforts with Common. Scott-Heron, in turn, acknowledged West’s contributions, sampling the latter’s 2007 single “Flashing Lights” on his final album, 2010’s I’m New Here.

The Bottle

Scott-Heron admitted ambivalence regarding his association with rap, remarking in 2010 in an interview for the Daily Swarm: “I don’t know if I can take the blame for [rap music]”. As New York Times writer Sisario explained, he preferred the moniker of “bluesologist.” Referring to reviews of his last album and references to him as the “godfather of rap”, Scott-Heron said: “It’s something that’s aimed at the kids … I have kids, so I listen to it. But I would not say it’s aimed at me. I listen to the jazz station.”

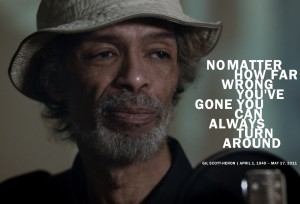

Following Scott-Heron’s funeral in 2011, a tribute from publisher, record company owner, poet, and music producer Abdul Malik Al Nasir was published on the Guardian website. Nasir’s birth name is “Mark Trevor Watson,” but he changed his name after being introduced to Islam by Jalal Mansur Nuriddin and Suliaman El Hadi (deceased), of the band The Last Poets, who he met through Scott-Heron. Titled “Gil Scott-Heron saved my life,” the tribute explains how Nasir met Scott-Heron during the period after the 1981 riots in Nasir’s home in Toxteth, Liverpool, UK. Following a series of unplanned events that established their relationship, Scott-Heron became a mentor to Nasir and helped him to build a life for himself after growing up illiterate in community homes. In the conclusion of his tribute, Nasir writes:

It’s three weeks since Gil died, and I’m still in shock. I’m 45, married with five children, and Gil has been the most important person to me throughout my adult life. His funeral in Harlem was a sombre affair. What touched me most was all the love in the room … After the service, I told Kanye my story and asked if he would take part in a tribute concert for Gil in Liverpool, the place where we met all those years ago and he took me under his wing. This is my way of saying: “Thank you Gil. You saved my life.”