Welcome to the weekend POU!

The final person featured in our series on Investigative Journalists, was not actually a journalist. However, through his own initiative, he became an investigator and managed to provide us with a wealth of history that we may never have known about African Americans in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. His desire to dispel the myths of white supremacy led to the discovery of thousands of inventions by African Americans.

Almost everything we know about early African American inventors comes from the dedicated endeavers of Mr. Henry E. Baker, a virtual unknown among African American inventors.

Little has been written about Henry, but it is known that he was born in pre-Civil War Mississippi, and that he was later admitted to the United States Naval Academy as a cadet midshipman. White prejudice drove him away from this institution, and he took a position as a “copyist” at the United States Patent Office in Washington, DC. While at the Patent Office, he enrolled in and graduated from Harvard University’s law school. He also rose to the position of Second Assistant Examiner at the Patent Office.

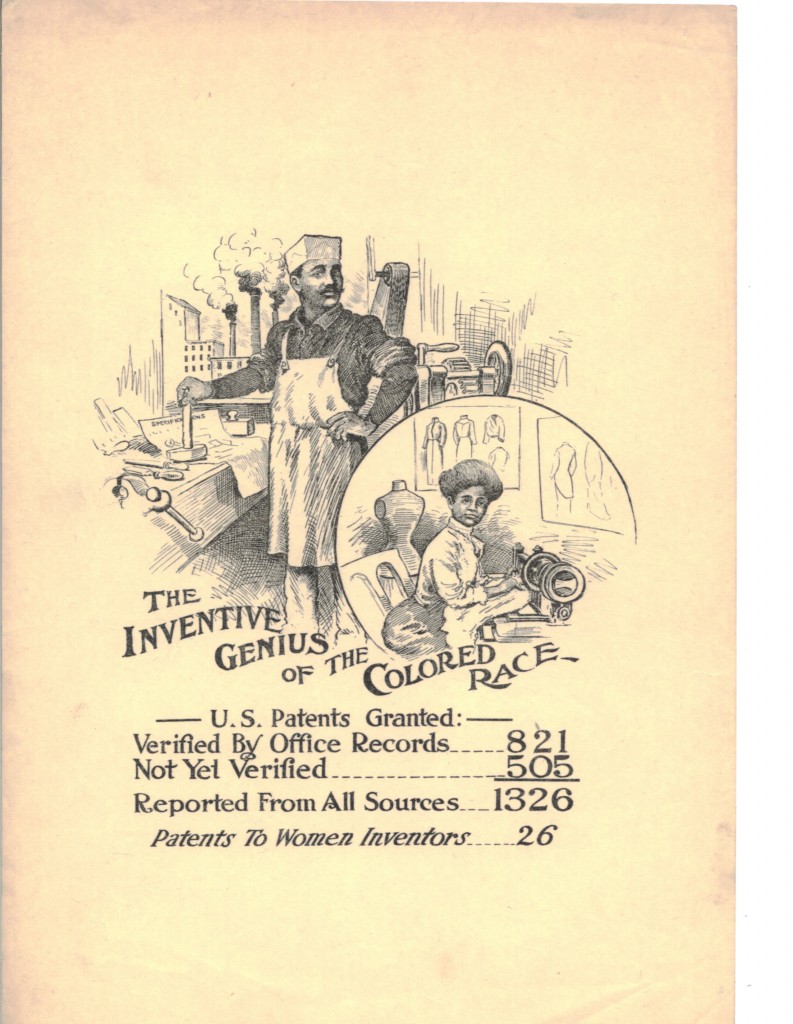

During his years at the Patent Office, Henry became fascinated at the number of inventions that came from “minds of color.” All around him, white Americans insisted that Negroes could not even suggest a new idea, much less try to patent one, yet Henry encountered Black inventors every workday. It became his passion in life to tell the world what African Americans could do with their minds.

With the consent of the Patent Office, Henry sent out some 8,000 letters to more than 12,000 registered patent attorneys in the United States, along with company presidents, newspaper editors and prominent African Americans. He asked them to tell him about any African American who had patented or tried to patent an invention.

Nearly 2,500 patent attorneys responded, stating that “they had never heard of a colored inventor, and never expected to hear of one.” Still, Henry’s investigation uncovered over 1,200 African American inventors. Of these, 800 gave permission for Henry to reveal their identities, because there had never been identifying passages on the patent application to indicate race. But the remaining inventors refused official identification, stating that such exposure would surely make sales of their inventions drop drastically–or cease altogether! The 800 verified inventions did not represent even half of the patents Henry knew for certain were filed by African Americans, and he was keenly disappointed. But he, too, realized that exposure meant jeopardizing sales.

Henry wrote an article on Negro inventors that appeared in Twentieth Century Negro Literature, 1900.He also compiled four large volumes of actual patent drawings for those inventions. Only one set was printed, and it is now housed as a part of the Howard University Negro Collections.

Henry later wrote a pamphlet called The Colored Inventor, which he timed to be published on the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. On the very last page, he promised to write a more detailed book on the subject of African Americans and their ingenius inventions, but he never did. Curiously, the very thing he fought so hard not to allow to happen to Black Inventors happened to him: he slipped into anonymity.

After the pamphlet was published, Henry seems to have disappeared into thin air. Nothing else was written about him, his proposed project, his life or his death.

We may not know much about him, but we know this at least: Henry Baker was the man who wrote it down.

Reprinted from The Black History Channel.