THE WEEKEND BABY!

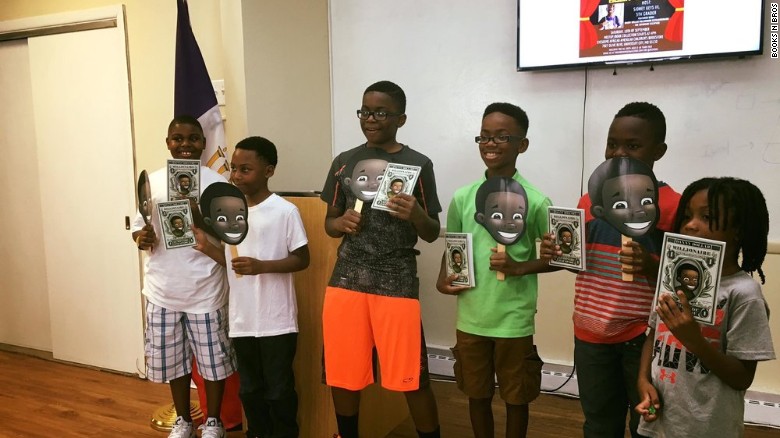

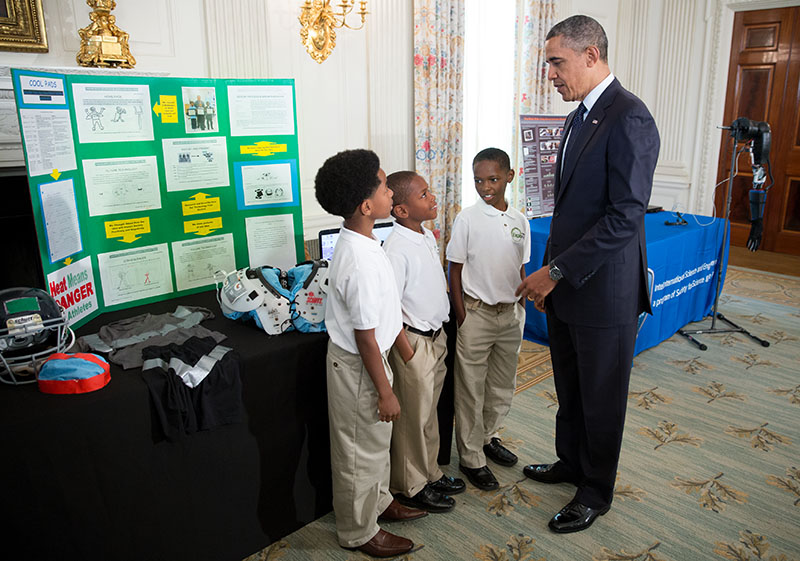

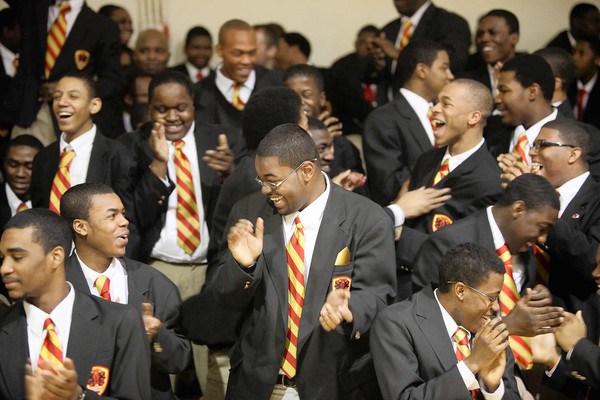

This series was heart-breaking and speaks to the depravity inflicted upon people of color in this country. I know these were tough reads, but necessary reads also. This one today, just 20 years ago. I purposefully chose to insert pics of young beautiful black boys to contrast the image put upon them by this “study.”

In 1998, Federal research-ethics officials investigated several psychiatric experiments in which 100 New York City boys, many of them black or Hispanic, were given the now-banned diet drug fenfluramine.

From the New York Times, April 15, 1998:

The three experiments took place at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, which is affiliated with Columbia University, at Queens College and the Mount Sinai School of Medicine over three years, ending in 1996. In the experiment at the New York Psychiatric Institute, 34 children, all of whom were 6- to 10-year-old black or Hispanic boys, were given intravenous doses of fenfluramine to test a theory that violent or criminal behavior may be predicted by levels of certain brain chemicals.

The investigation was prompted by criticism from patient advocacy groups over whether these children may have been used in experiments in which they had no hope of medical benefit, but may have been exposed to substantial risk. Federal regulations prohibit such experiments except under unusual conditions.

The critics have also asked the investigators to examine possible bias in the racial makeup of the experiments. ”What value does the President’s apology for Tuskegee have when there are no safeguards to prevent such abuses now?” asked Vera Sharav, the director of the New York patient advocacy group called Citizens for Responsible Care in Psychiatry and Research, referring to the infamous experiment in which black men with syphilis were not treated but were instead observed.

”These racist and morally offensive studies put minority children at risk of harm in order to prove they are generally predisposed to be violent in the future,” she said.

The researchers defended their efforts as a legitimate attempt to understand the roots of violence.

The children were given a single fenfluramine pill and were kept in a hospital bed for at least five hours with a catheter in their arm while blood samples were taken. They were without food for at least 17 hours.

The drug given to the children, fenfluramine, was a component of the diet drugs called Fen-Phen. The drugs were taken off the market after some adults who had taken them in combination for months were found to have heart-valve defects. In all three experiments, the children received only small, one-time doses of fenfluramine, so experts in the use of that drug say it is unlikely their hearts were damaged.

The boys who were given the drug were the younger brothers of delinquents. The researchers found them through court records and by interviewing mothers to find those who had what the scientists described as ”adverse rearing practices.” The mothers were then asked to bring the children into the experiment. In return, they were given $125.

Articles on the experiments were published in scientific journals last fall. Later in 1997, Ms. Sharav reported the studies to the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, a panel that counsels the President. The commission is now reviewing the Federal Government’s rules on experiments with ”vulnerable subjects,” such as children and mental patients.

Disability Advocates, Inc., a nonprofit group based in Albany that helps people with disabilities in human rights cases, referred the experiments to the Federal Office of Protection from Research Risks of the Department of Health and Human Services.

On Monday, Dr. Gary Ellis, chief of the Federal office, confirmed that a preliminary investigation has begun and estimated that it would take months to complete.

Researchers at Queens College and Mount Sinai did not offer extensive comment on the experiments, but said in a statement yesterday, ”Mount Sinai denies that the research conducted at our institution was in any way illegal, unethical or otherwise improper.”

The chief author of the Psychiatric Institute study, Dr. Daniel Pine, declined to comment, but the director of the Psychiatric Institute, Dr. John Oldham, said in interviews two weeks ago that such studies are very important to study the biological basis of behavior.

”Is there or is there not a correlation between certain biological markers and conduct disorders or antisocial behavior?” Dr. Oldham said. ”This study was an effort to look at this with a relatively simple method using fenfluramine.”

In the two experiments published jointly by researchers from Queens College and Mount Sinai, the subjects were 66 boys between ages 7 and 11 with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The boys were taken off their medication for attention deficit and intravenously given fenfluramine to measure for a chemical they believe is linked to aggression.

A spokesman for Mount Sinai, Mel Granick, would not disclose what percentage of the boys in the Queens and Mount Sinai studies were black or Hispanic, saying only that the boys reflected the ”ethnically diverse population of our catchment area.”

Federal research-ethics officials found fault with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the Research Foundation of the City University of New York for the way they conducted psychiatric experiments that injected hyperactive children with the now-banned diet drug fenfluramine.

But the yearlong investigation, prompted by complaints from patient advocacy groups, found no violations by the New York State Psychiatric Institute in the conduct of similar experiments, although some of the advocates are questioning that conclusion.

Federal officials said that the Mount Sinai experiments exceeded the limits of minimal risk to the children, failed to inform patients and their parents of their foreseeable risks and discomforts and were not properly reviewed by the medical school’s board responsible for enforcing Federal research requirements.

In the case of the CUNY experiments, investigators found that the university board responsible for overseeing the research failed to review it from 1989 through 1996 and failed to consider the special safeguards Federal rules require when subjects are children.

Federal officials did not find that any of the approximately 150 children involved in the research had been harmed, and neither institution was fined. But both Mount Sinai and CUNY must submit to tighter Federal oversight on their research with human subjects until they complete corrections. The fenfluramine research was conducted over three years and ended in 1996.

Letters to the three institutions giving details of the findings were released yesterday by the Office for Protection from Research Risk, part of the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees federally financed research with human subjects.

The Mount Sinai and CUNY experiments studied the effects of fenfluramine in children with a diagnosis of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Fenfluramine is a component of the diet-drug combination known as Fen-Phen, which was pulled from the market in 1997 when it was linked with heart damage. The State Psychiatric Institute, which is affiliated with Columbia University, gave the drug intravenously to black and Hispanic boys aged 6 to 10 with delinquent older brothers to study a theory that violent behavior could be predicted by levels of serotonin, a brain chemical.

John M. Oldham, director of the State Psychiatric Institute, said his research had been vindicated by the Federal findings.

”From the very beginning, we have maintained that Psychiatric Institute has conducted this research in a completely ethical manner that conforms with Federal and state regulations,” he said yesterday. ”It’s very gratifying to know that the Federal Government has reached the same conclusions and has gone further to compliment us on our enthusiastic and dedicated protection of the people who participate in research.”

But the patient advocacy groups that had complained to the Government were sharply critical of the findings exonerating the Psychiatric Institute. They contended that the Federal investigation looked only at paperwork compliance in a narrow procedural area, not at the substance of how the children were chosen or what had been done with them.

”It’s a whitewash,” said Adil Shamoo, a bioethicist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who is a founder of the patient advocacy group, Citizens for Responsible Care in Psychiatry and Research, that sought the investigation. ”The biggest flaw is they never talk to the victims, the patients, the families. I realize checking the paperwork has some significance, but it’s a very poor representation of what actually happened.”

Dr. Daniel Neuspiel, a pediatrician who treated one of the subjects of the Psychiatric Institute, said the boy ”had clear symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder that were a consequence of his participation in this study.”

But the letter to the foundation that oversees the Psychiatric Institute praised the members of its institutional review board and said that the board’s membership ”has the diversity, including consideration of race, gender and cultural backgrounds and sensitivity to such issues as community attitudes.”

In investigating the two other institutions, however, Federal officials found problems in the fenfluramine study ”consistent with systemic deficiencies” in the way they protected other human subjects of its research.

In the Mount Sinai experiments, research procedures included placing an intravenous catheter in the children for drawing blood, administering fenfluramine and conducting genetic testing, not only in about 100 children with a diagnosis of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, but also in four children without the disorders who were used as controls.

Federal officials said the injection of those children would not have been allowed under Federal regulations even if proper procedures had been followed, and directed Mount Sinai to contact them or their parents to ask about their experience and inform them of the researchers’ violation of Federal requirements.

Mel Granick, a spokesman for Mount Sinai, called the Federal findings ”a retrospective judgment,” adding, ”It was our firm belief at the time that the research was being conducted that it presented no risk to any of the participants, and to this day there is no evidence that any participants in the study suffered any injury.”

John Hamill, a spokesman for CUNY, which was faulted for failing to review the study, said the university ”will continue to work to correct, as it has been doing for some time, the procedural and administrative shortfalls identified.”

Much of the criticism of the Psychiatric Institute’s research focused on whether minority children had been singled out for experiments in which they were exposed to substantial risk but had no hope of medical benefit.

Federal investigators found that unlike Mount Sinai’s review board, the review board at the institute had correctly determined that the research involved greater-than-minimal risk and no prospect of direct benefit to individual subjects, but ”was likely to yield generalizable knowledge about the subject’s disorder or condition.”

”It’s been well established that younger brothers of adjudicated delinquents are at high risk to go down the same wrong turn,” Dr. Oldham said. ”They weren’t squeaky clean.”

He added, ”We were trying to study an enormously important problem — and this was a study going on before Littleton — youth, violence and delinquency.”

A 6-year-old boy who was selected for the institute’s research because his teen-age brother was in custody as a juvenile delinquent has filed suit in Federal court against the institute, Columbia University and various city agencies.

His lawyer, Rudy M. Brown, said the boy’s mother agreed to the child’s participation after she was contacted by the city’s Department of Probation because she was afraid that refusal would hurt her older son. Whether the institutional review board performed in conformance to regulations, Mr. Brown said, ”The fundamental premise of the study was flawed from a civil rights point of view.”

Articles on the experiments, published in scientific journals, concluded that a combination of chemical and environmental factors affected children’s behavior.