Good Morning POU!

The last Miss Anne of the week is yet another biddy that Zora Neal Hurston scoped out and realized “ok, let me help this white woman find purpose by letting her support my life.” *wipes tear*, this just makes me happy.

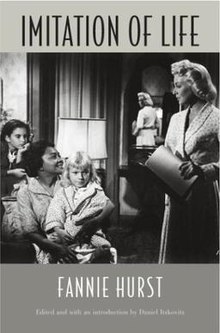

Fannie Hurst (October 19, 1885 – February 23, 1968) was an American novelist and short-story writer whose works were highly popular during the post-Word War 1. One of her most famous novels was actually conceived by Zora Neal Hurston, the classic book turned movie, Imitation of Life. Hurst took Zora’s idea, and ran with it.

More than anything else, Hurst thrilled to her growing reputation as one of the country’s most important “friends of the Negro,” a public stance even more outré than feminism. In fact, Fannie Hurst came relatively late to the cause. It was not until the mid-1920s, having first gone to Harlem with Carl Van Vechten, that she began to take a serious interest in what she called “black matters.” Although she acted as a judge for a number of Harlem’s important literary contests, into the mid-1920s she was still dismissing the importance of race as “something I don’t particularly think about one way or the other.” She did, however, as she remarked in one interview, think that some blacks were “lovable characters.”

In 1926, she joined the board of the National Health Circle for Colored People (NHCCP). The NHCCP partnered with nurses’ organizations to push for more public health services for blacks, especially in the South, and “to create and stimulate among the colored people, health consciousness and responsibility for their own health problems.” Like so many white-led social welfare organizations at the time, it took for granted that blacks needed white instruction in hygiene and personal responsibility, rather than equitably distributed social resources. In 1927, she lent her name to the organization’s fund-raising appeal, urging donors to give generously to a “languid . . . happy friendly race.”

After 1928, Hurst’s name increasingly appeared on the board lists of organizations such as the NAACP and the Urban League. Her involvement was largely nominal, however. Impatient with the routine work of political organizing and the tedium and anonymity of grassroots work, she preferred judging literary contests, giving talks, penning appeals, and mentoring individuals: tasks that made use of her name and reputation. She rarely attended the board meetings for which she lent her large apartment. Instead, she left instructions with her staff. Her caveat for organizational participation was that fellow members accept “that I was not in a position, owing to countless obligations, . . . to give either time or money.” It is hard to imagine that the apartment she lent was a particularly congenial place for committee meetings. It had forty-foot ceilings, dark woods, oversize medieval art (Catholic Madonnas and crosses), red brocade curtains, calla lilies (Hurst’s signature flower), and numerous portraits of herself; it was a stylized shrine to a highly constructed image, as much a stage set as a home.

It was into that space and that image that Hurst tried to shoehorn Zora Neale Hurston, another outsize personality with a carefully constructed image to maintain. Hurston caught Hurst’s attention at the dinner for the 1926 Opportunity awards, which Hurst judged. Throwing a red scarf around her shoulders and yelling out the title of her award-winning play, Color Struck , Hurston was clearly the most flamboyant person in the room. Hurst was unused to such competition, and it is to her credit that she gravitated toward the woman who upstaged her. Fannie Hurst was by then the highest-paid writer in the United States, with many novels and hundreds of stories already in print.

She was also probably the most influential and widely known white person to interest herself in black New York. Hurston, by contrast, was a recent arrival to New York, struggling to make ends meet. She had appealed for support to both Arthur A. Schomburg and the hairdressing entrepreneur Annie Pope Malone (the Madam C. J. Walker of the Midwest) but both had turned her down. Annie Nathan Meyer had already taken an interest in helping her get into Barnard but lacked sufficient funds to cover all of Hurston’s expenses; she encouraged her friend Fannie Hurst to help out as well. Knowing Hurst proved an enormous advantage to Hurston, then Barnard’s only black student. “Your friendship was a tremendous help to me at a critical time. It made both faculty and students see me when I needed seeing,” Hurston wrote to her. Hurston suddenly had two very well-known Jewish women friends, both of them well-established writers. “I love it! . . . To actually talk and eat with some of the big names that you have admired at a distance,” Hurston told a friend. Her unabashed delight contributed to Hurst’s ongoing self-crafting.

So Hurst helped out enthusiastically, enlarging Hurston’s social contacts, introducing her to Stefansson, writer Irvin Cobb, Paramount Pictures co-founder Jesse Lasky, actress Margaret Anglin, and others. It was timely assistance, since Hurston was down to her last “11 cents.” And Barnard, which catered to upper-class women, was requiring her to pay for a gym outfit, a bathing suit, a golf outfit, and a tennis racket. Far worse, some of her Barnard professors were assigning “C” grades to her examinations before she’d even sat for them. She was feeling, she said, like a “Negro Extra.” Hurst was entranced with Hurston. She believed she saw an essential, primitive blackness in her. “She sang with the plangency and tears of her people and then on with equal lustiness to hip-shuddering and finger-snapping jazz,”

Hurst wrote approvingly. She was as “uninhibited as a child.” To Hurst, Hurston was a humble native genius, close to the soil, a delightful “girl” with the “strong racial characteristics” of humor, humility, and wit. She saw in Hurston a “sophisticated negro mind that has retained many characteristics of the old-fashion and humble type.” She praised her “talent,” her “individuality.” Mostly, she delighted in what she called Hurston’s “most refreshing unself-consciousness of race.” Hurst hired Hurston as a chauffeur and personal secretary—“the world’s worst secretary.” Hurston was to run errands and answer letters and the telephone. “Her shorthand was short on legibility, her typing hit-or-miss, mostly the latter, her filing, a game of find-the-thimble. Her mind ran ahead of my thoughts and she would interject with an impatient suggestion or clarification of what I wanted to say.

If dictation bored her, she would interrupt, stretch wide her arms and yawn: ‘Let’s get out the car, I’ll drive you up to the Harlem bad-lands or down to the wharves where men go down to the sea in ships.’” Fortunately, Hurst loved to visit out-of-the-way places and Hurston loved to drive. Invariably, Hurst took the backseat. On one of their driving trips, Hurston took Hurst to see her hometown, Eatonville, Florida. Eatonville was the nation’s first incorporated black town, Hurston’s folklore source, and her emotional touchstone. To her it was a utopian world where blacks lived near whites “without a single instance of enmity”; where people lived a “simple” life of “open kindnesses, anger, hate, love, [and] envy”; where you “got what your strengths could bring you.”

But Hurst saw “squalor” instead of the splendor dear to Hurston’s heart. She looked pityingly on what Hurston claimed as the “deserted home” of Hurston’s family, “a dilapidated two-room shack.” The building, in fact, had never housed the family. But Hurst never found out that Hurston had never lived in such a shack. On the contrary, the family home in Eatonville was a gracious eight-room property on five acres, a “roomy house” on a nice “piece of ground with two big Chinaberry trees shading the front gate and Cape jasmine bushes with hundreds of blooms on either side of the walks . . . plenty of orange, grapefruit, tangerine, guavas and other fruits” in the yard. Hurston clearly understood, and provided, what Hurst expected to see.

It was on one of their car trips, just at this juncture, in June 1931, that Hurston—who was also collaborating with Annie Nathan Meyer and under increasing pressure from Charlotte Osgood Mason—furnished Hurst with the material for Imitation of Life. Hurst told Hurston that they were motoring toward Vermont to look at property and visit her literary agent, Elisabeth Marbury, who had just taken Hurston on board as well. Marbury was a powerhouse, and Hurston would naturally have been eager to solidify the new relationship with a social visit. Hurston’s contract with Mason had ended that March, freeing up her publication plans but also leaving her without the regular financial support she’d grown accustomed to. She had two manuscripts under revision but no acceptances and Franz Boas looking over one shoulder, Mason glaring over the other. With fewer and fewer outlets for black literature available after the stock market crash, good relations with both Hurst and Marbury could make all the difference.

Hurst returned to New York with the core of the novel that would ensure her legacy for decades to come. Hurston, on the other hand, returned to New York to find that one of her current benefactors, Mason, and Locke were furious with her and banishing her to the South.

Imitation of Life was an important experiment for Hurst, designed to prove to the modernists who ignored her and the critics who derided her that sentimentality, a deeply female literary form, could address the “hard” social issues. She had a lot riding on the novel. But she needed Hurston’s help. She wrote a series of letters, begging Hurston to return to New York and review her draft. Hurston was in Florida working hard on her folk opera and trying to keep that fact from Mason, who wanted her to work on Barracoon. Hurst desperately wanted her advice on the manuscript, but Hurston dodged her, sick of being anyone’s “pet Negro.”

Hurst finished the novel, her only black story, on her own. It shows. Set just beyond the bustling Atlantic City boardwalk, Imitation of Life tells two unhappy stories of passing: white Bea Pullman (née Chipley)’s brief passing for a man and black Peola Johnson’s lifelong passing for white. Bea’s passing costs her dearly, but it is excused because of the disadvantages imposed on women in a world of sexual double standards, a frequent theme of Hurst’s. But Peola’s passing, although occasioned by a similar desire to escape the racial double standard, is neither excused nor forgiven in the novel. Peola’s unhappiness is depicted as her own fault, the consequence of her sinful efforts to pass.

Her novel was a special disappointment to a community deeply invested in the rich emotional potential of racial identity and deeply invested, as well, in expectations of its Negrotarians. Many Harlemites joined the fracas over Imitation of Life in 1933 and 1934 when the first film version of the novel appeared. But Hurston kept her peace. Although she supported Hurst in private letters, she refrained from saying a word in public. Hurston must have seen, and perhaps hoped that others would not notice, that the character Delilah was only half Aunt Jemima. Hurst’s Delilah was also half Hurston, or rather half what Hurst perceived to be Hurston’s racial nature. She was painfully aware of the traits Hurst prized in her: “childlike manner . . . no great profundities but dancing perceptions . . . sense of humor,” and delightful “fund of folklore.” The lack of “indignation” and “insensibility” to racial slights, which Hurst imagined she saw in Hurston, were precisely the materials out of which Delilah was created. She was a “margarine Negro,” as Hurston called white-authored black caricatures, a figure built in Hurst’s image of Hurston, an insult at every level and, perhaps, Hurst’s retaliation for Hurston’s refusal to help.

Yet, Hurst evidently did not expect a black backlash. She was “stunned when she found her best-selling novel Imitation of Life the subject of fierce debate and parody” and “horrified by the sharp criticism” in Opportunity. Her novel probably had a profound effect on how the major writers of the Harlem Renaissance viewed friendship with whites and the possibilities of interracial intimacy.

Just after Imitation of Life appeared, Hurston wrote an essay entitled “You Don’t Know Us Negroes,” perhaps her most forceful statement about how much white writers get wrong when they try to write about blacks. Their writings, she argued, “made out they were holding a looking-glass to the Negro [but] had everything in them except Negroness.” Without naming Hurst, Hurston’s essay addressed every flaw of Hurst’s novel, from its minstrel-ridden use of dialect and malapropisms to its treatment of Peola. “If a villain is needed” in a white novel, Hurston noted, white writers just “go catch a mulatto . . . yaller niggers being all and always wrong.” Those “margarine Negroes,” Hurston went on, are found especially in “popular magazines”: Fannie Hurst’s primary outlet. Hurston listed the white writers she called “earnest seekers”: DuBose Heyward, Julia Peterkin, T. S. Stribling, and Paul Green. Fannie Hurst was not included. It was high time,

Hurston argued, for white writers to earn the privilege of writing about blacks. “Go hard or go home,” she concluded angrily. Intended for The American Mercury , the essay was pulled at the last minute and never published. Possibly, Hurst never saw it. Hurston tried again, and Hurst certainly saw Hurston’s essay “The Pet Negro System,” published in 1943. Written as a mock sermon, the essay takes a mock document called The Book of Dixie as its text:

And every white man shall be allowed to pet himself a Negro. Yea, he shall take a black man unto himself to pet and to cherish and this same Negro shall be perfect in his sight. Nor shall hatred among the races of men, nor conditions of strife in the walled cities, cause his pride and pleasure in his own Negro to wane.

The “Pet Negro,” Hurston explained, “is someone whom a particular white person or persons wants to have and to do all the things forbidden to other Negroes”; by pointing to his or her pet, the white person decries outside criticism. Even if she’s a troublemaker and difficult—as pets often are—talking back to him and refusing to do all he asks, he’s only too happy to heap rewards on her, privileges foreclosed to all other blacks. Again, Hurston did not name Fannie Hurst. She did not need to. All of Harlem had known of her friendship with Hurst. And Hurst certainly would have been familiar with Hurston’s masterpiece, Their Eyes Were Watching God , published in 1937, with its suggestion that trying to speak across the racial divide, or develop any meaningful friendships with whites, is as much a waste of time as “letting the moon shine” down your throat. Hurst’s repeated insistence on “un-selfconsciousness” about race applied only to blacks. She did not believe it did—or should—apply to her. Her demand for “color blindness” was a one-way street, what Patricia Williams calls a “false luxury” that pretends that what matters a great deal does not matter at all.

Feeling little for either whiteness or blackness, Hurst allowed herself to be intellectually fascinated with blackness while whiteness went unexamined. That kind of unself-consciousness about race is fundamental to what George Lipsitz calls the “possessive investment in whiteness”: the privilege of not seeing oneself, if white, as raced, and the idea that one’s own whiteness is a neutral default, nothing more than the way things are. Music and literary critic Baz Dreisinger, one of the few academics to write about “reverse” racial passing, suggests that we can differentiate “admirable” white identifications with blackness from “onerous” ones by the presence or absence of a self-critical distance.

Hurst’s own background might have given her the distance Dreisinger describes. As a Jew, she was not considered entirely white. The closer she came to blackness, however, the whiter she became. Had she taken more note of that phenomenon, as well as taking professional advantage of it, her story of identities crossed and recrossed would have been richer. Whereas Lillian Wood, Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, Annie Nathan Meyer, and Charlotte Osgood Mason all confounded available ideas of race and identity, whether meaning to or not, Fannie Hurst, by and large, affirmed the status quo. The fact that Hurst could so easily avoid any consequences for that failure makes what other white women—from Lillian Wood to Nancy Cunard—willingly incurred for their transgressions all the more remarkable.

Hurst’s failure of even her own liberal ideals serves as a painful reminder of how unpredictable—even to herself—Miss Anne’s involvement with black lives could be.