![]()

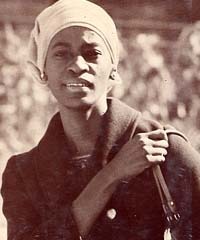

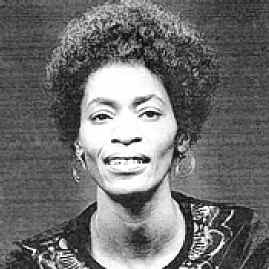

Today’s focus is the fierce Carolyn Rodgers, a revolutionary Chicago poet of the Black Arts Movement.

Carolyn Rodgers(1940-2010), a Chicago poet who first learned her trade in the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) Writer’s Workshop meetings and Gwendolyn Brooks’s Writers Workshops, was distinctive as a new black woman poet in the late 1960s, when she published her first two books, and for her vehement adherence to the Black Arts program. She was also the founder of one of America’s oldest and largest black presses, Third World Press.

Noted for her vulgarity and other excesses, Rodgers was quickly and heavily criticized by male leaders of the Black Arts Movement for her unladylike uses of the very rhetorical excesses they had promoted. In his introduction to Rodgers’ second volume of poetry, Songs of a Black Bird (1969), David Llorens hinted at the tensions caused by her appropriation of the masculinist style: “Some ‘revolutionary’ brothers had put the ‘bad mouth’ on her, and had run down something as old as … and far more insidious than ‘nigger bitches ain’t shit.’ And they had me check the sister out, looking for a badge that ain’t never been there as far as I know or think” . Llorens wrote the introduction because he found no evidence of such treachery (the “badge” of bitchiness that he says never existed), viewing her rhetorical vigor as “new energy” that would aid rather than undermine the revolution.

Still, near the end of that same volume, Rodgers responds to critics who dictate a more conventionally feminine role for black women. In “The Last M.F.”, she promises to stop employing vulgar language in her poems; like Dickinson’s excessive compliance when her brother asks her to write more simply (“As simple as you please, the simplest sort of simple”), Rodgers vows never again to use obscenities like “mother fucker,” but she does so in lines that obviously savor this last opportunity for such expressiveness:

they say,

that i should not use the word

muthafucka anymo

in my poetry or in any speech i give.

they say,

that i must and can only say it to myself

as the new Black Womanhood suggests

a softer self

a more reserved speaking self. they say,

that respect is hard won by a woman

who throws a word like muthafucka around

and so they say because we love you

throw that word away, Black Woman …

i say,

that i only call muthafuckas, muthafuckas

so no one should be insulted.

Although in “The Last M.F.” Rodgers says she will stop using profanity, she continues using the “menacing word” at least eleven times throughout the poem, blatantly making jabs at men and their ideas of how a woman should speak and behave. Here too, Rodgers mocks the new Black Womanhood which she believes, paradoxically, promotes women to be silent.

By the 1970s, Rodgers was distilling her language and militant persona into poetry that was deeply concerned with religion, God, and the quest for inner beauty. The change from militant views to more religious views can be seen in her 1975 poem “and when the revolution came.” The repetition in the first four verses show a constancy in the black church communities:

and they just kept on going to church

gittin on they knees and praying

and tithing and building and buying

The implied criticism here is that while the militants were busy telling other black people how they should live to improve their lives, the black church communities were busy making black communities better. In stanzas 1 -5, Rodgers notes that the militants try to change the hair styles, the dress, any association with whites, the food eaten by blacks, and what the militants termed “white man’s religion.” According to Friedrike Kaufel, these changes “are petty ones.”[7] These changes were quietly and passively resisted by the church members, who continued “going to church” and “tithing and building and praying.” Stanzas 6-8 show the militants wanting to build new institutions for black children, and realizing that while the militants were only using words, in the form of orders, to make changes, the churches were actually making needed changes in black neighborhoods. Rodgers shows transformation from militant views to religious views in Stanza 8:

and the church folks said, yeah.

we been waiting fo you militants

to realize that the church is an eternal rock

now why don’t you militants jest come on in

we been waitin for you

we can show you how to build

anything that needs building

and while we’re on our knees, at that.

In these actions, the church members have long before reached the state of solidarity among themselves that the militants finally call for in Stanza 6

Life and Awards

Carolyn got her start in the literary circuit as a young woman studying under Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks in the South Side of Chicago.

She became distinctive as a new black woman poet in the 1960s with the publication of her first two books, Paper Soul and Songs of a Blackbird (Chicago: Third World Press, 1969). Following the national success of Paper Soul, Rodgers was awarded the first Conrad Kent Rivers Memorial Fund Award. Rodgers also won the Poet Laureate Award from the Society of Midland Authors in 1970. She then went on to receive an award from the National Endowment of the Arts, following the publication of Songs of a Blackbird. In 1980, Rodgers won the Carnegie Writer’s Grant. She won the Television Gospel Tribute in 1982 and the PEN Grant in 1987. In 2009, Rodgers was inducted into the International Literary Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent at the Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature and Creative Writing.