Good Morning POU

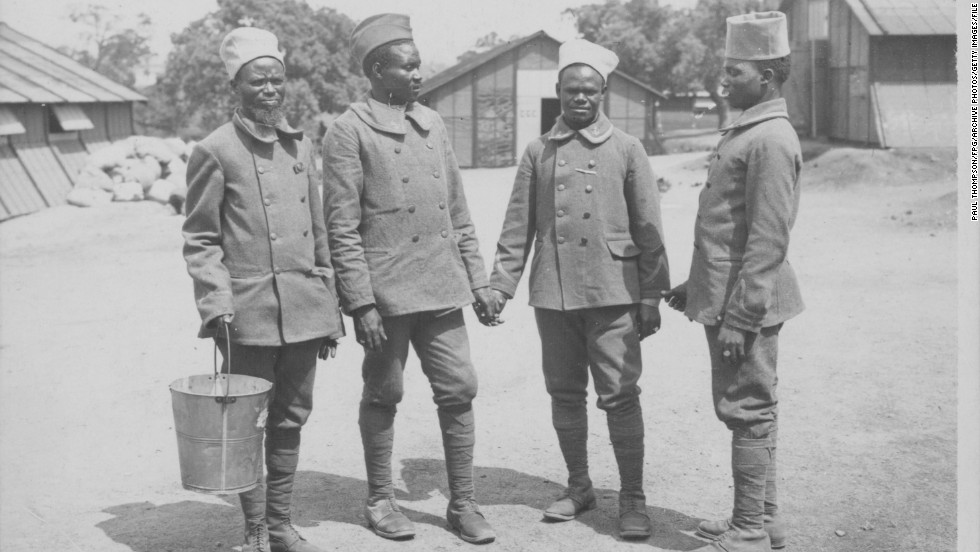

Returning African American veterans after the first World War were met with a familiar “tenacious and violent white supremacy,” and their status as veterans made them special targets for white aggression.

Though hailed as a hero during the war, Sergeant Henry Johnson was almost completely disabled from his wounds. Subject to the racially discriminatory administration of veterans’ benefits, he and many other black veterans were denied medical care and other assistance. After he publicly objected to the mistreatment of black veterans, Sergeant Johnson was discharged with no disability pay and left to poverty and alcoholism. Henry Johnson, patriot and war hero, died penniless and alone in 1929 at just 32 years old.

In Congress, the fear that returning soldiers posed a threat to racial hierarchy in the South was a matter of public record. On August 16, 1917, Senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi, speaking on the Senate floor, warned that the reintroduction of black servicemen to the South would “inevitably lead to disaster.” For Senator Vardaman and others like him, black soldiers’ patriotism was a threat, not a virtue. “Impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag, inflate his untutored soul with military airs, teach him that it is his duty to keep the emblem of the Nation flying triumphantly in the air,” and, the senator cautioned, “it is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected.”

White Americans also feared that meeting black veterans’ demands for respect would lead to post-war economic demands for better working conditions and higher wages and would encourage other African Americans to resist Jim Crow segregation and racially oppressive social customs. Veterans’ experience with firearms and combat exacerbated fears of outright rebellion. In addition, the prevalent stereotype of black men as chronic rapists of white women — frequently used to justify lynchings — was amplified by accounts of wartime liaisons between black troops and white French women. Such acceptance by French women, it was claimed, would give black veterans the idea that they had sexual access to white Southern women. So as black soldiers returned home to enjoy peace, many Southern whites literally “prepared for war.” Racial violence targeting African American veterans soon followed.

Countless African American veterans were assaulted and beaten in incidents of racial violence after World War I. At least 13 veterans were lynched. Indeed, during the violent racial clashes of Red Summer, it was risky for a black serviceman to wear his uniform, which many whites interpreted as an act of defiance.

On November 2, 1919, Reverend George A. Thomas, a first lieutenant and chaplain, and at least one other black veteran were attacked in Dadeville, Alabama, for wearing “Uncle Sam’s uniform.”

There are many accounts of whites in the South accosting black veterans at railroad stations and stripping them of their uniforms. Three months after returning from the war, black veteran Ely Green was wearing his army uniform while driving in downtown Waxahachie, Texas, when a sheriff’s deputy threatened to “whip [it] off him.” The deputy and three white police officers took Mr. Green out of his car and dragged him for a block, then beat him against a wall with their fists and the barrels of their guns while 50 other men watched. Mr. Green was nearly shot and killed, but a prominent white man who knew him drove by and intervened. After the brutal attack, Mr. Green fled Texas, leaving “the happiest home” and “the only dad” he had known, and did not return to Waxahachie for more than 40 years.

On April 5, 1919, a 24-year-old black veteran named Daniel Mack was walking in Sylvester, Georgia, when he accidentally brushed up against a white man as they passed each other. The white man responded angrily and an altercation ensued, leading to Mr. Mack’s arrest. At his arraignment, Mr. Mack said, “I fought for you in France to make the world safe for democracy. I don’t think you’ve treated me right in putting me in jail and keeping me there, because I’ve got as much right as anyone to walk on the sidewalk.” The judge responded, “This is a white man’s country and you don’t want to forget it.” He sentenced Mr. Mack to 30 days on a chain gang. Mr. Mack was serving his sentence when, on April 14, at least four armed men seized him from his cell and carried him to the edge of town, where they beat him with sticks, clubs, and the butts of guns, stripped him of his clothes, and left him for dead. Despite multiple skull fractures, Mr. Mack made his way to the home of a black family who helped him to escape town.

Daniel Mack survived and managed to flee the South, but many other black veterans did not make it out alive. In Pine Bluff, Arkansas, when a white woman told a black veteran to get off of the sidewalk, he replied that it was a free country and he would not move. For his audacity, a mob took him from town, bound him to a tree with tire chains, and fatally shot him as many as 50 times.

African Americans served in the Civil War, World War I, and World War II for the ideals of freedom, justice, and democracy, only to return to racial terror and violence. American individuals and institutions intent on maintaining white supremacy and racial hierarchy targeted black veterans for discrimination, subordination, violence, and lynching because they represented the hope and possibility of black empowerment and social equality. That hope threatened to disrupt entrenched social, economic, and political forces, and to inspire larger segments of the black community to participate in activism that could deal a serious blow to the system of segregation and oppression that had reigned for nearly a century and was rooted in a myth of racial difference older than the nation itself.

Despite the overwhelming injustice and horrific attacks black veterans suffered during the era of racial terror, they remained determined to fight at home for what they had helped to achieve abroad. This commitment directly contributed to the spirit that would launch the American Civil Rights Movement, and the courage that would sustain that movement through years of violent and entrenched opposition. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Medgar Evers of the Mississippi NAACP, and Charles Sims and Ernest Thomas of the Deacons for Defense, are just a few leaders of the civil rights era who returned to the United States as World War II veterans who were targeted for violence but determined to make change.

Highlighting and honoring the particular burden borne by black veterans during the lynching era is critical to recovering from the terror of the past as we face the challenges of the present.