Some clubs are still active. The Houston Heights Woman’s Club and The Women’s Club of Forest Hills have found ways to reach out to younger residents in the community as recently as 2007 with the creation of an evening group. Some clubs have had success in creating programs that are meant to be attractive to younger women. Shrilee Haizlip, president of the Ebell Club in Los Angeles, emphasizes what makes women’s clubs unique: “It is a wondrous thing to be constantly surrounded by three generations of women.”

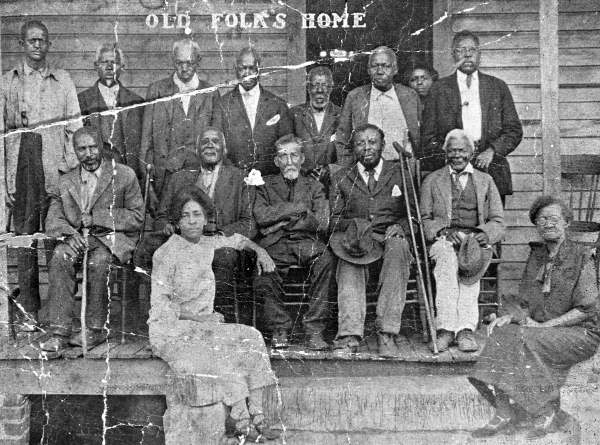

Women’s clubs continue their original missions of concern for the welfare of their communities. The GFWC gives out the Croly Award for excellence in journalism on topics relating to women. The GFWC also provides scholarships for women, especially those who have survived domestic violence. The NACWC continues to be one of the top ten non-profit organizations in the United States. It has adopted modern issues to tackle, such as fighting AIDS and violence against women. Many of today’s women’s clubs also provide cultural opportunities for their communities. Other groups continue to support their original missions, such as the Alpha Home, which provides care for elderly black people. Women’s clubs that exist today were adaptable in response to societal changes over time.

Women’s clubs, especially during the Progressive era, helped shape their communities and the country. Many progressive ideas were pressed into action through the resources of women’s clubs, including kindergartens, juvenile courts, and park conservation. Women’s clubs, many with their literary backgrounds, helped promote and raise money for schools, universities, and libraries. Women’s clubs were often at the forefront of various civil rights issues, denouncing lynching, promoting women’s rights and voting rights.

Women’s clubs helped promote civil rights, as well as improving conditions for black women in the country. A woman’s club in California, the Fannie Jackson Coppin Club, was created by African Americans to “provide hospitality and housing services to African-American visitors who were not welcomed in the segregated hotels and other businesses” in the state. Some white woman’s clubs promoted desegregation early on, though these efforts were small in scope. The Chicago Woman’s Club admitted a black member, Fannie Barrier Williams, only after a long approval process, which included the club deciding not to exclude anyone based on race. Few clubs worked together across racial boundaries, although the YWCA and the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL) sometimes welcome bi-racial collaboration.

The Woman’s Missionary Council for the southern Methodist church spoke out against lynching. Women’s clubs, like the Texas Association of Women’s Clubs also denounced lynching. The purpose of the ASWPL was to end lynching in the United States.

Women’s groups, like the NACWC, began to support desegregation in the 1950s. The Montana Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs led campaigns for civil rights between 1949 and 1955. They also helped draft anti-segregation legislation. The initial organizer of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 was the Woman’s Political Council of Montgomery.

African-American women’s clubs like the NACW not only fought for women’s suffrage, but also for the right of black men to vote. Many black women were involved in groups like the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Women involved in the National Baptist Woman’s Convention also supported suffrage.