In the early days of the film industry, for most American silent films, minorities were generally played by white actors in make-up. When actual minorities were cast, roles were generally limited. Latinos in silent films usually played greasers and bandits; Asian-Americans played waiters, tongs and laundrymen; and blacks usually played bellboys, stable hands, maids or simple buffoons. Early film depictions of black characters were highly offensive, including those in the films Nigger in the Woodpile, Rastus, Sambo and The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon. Not surprisingly, both Asian-Americans and blacks responded by launching their own alternative cinemas. But while Asian-American Silent Cinema quickly faltered, black cinema (blessed with a much larger audience) flourished and soon many so-called race movies were being made by both black and white filmmakers for black filmgoers.

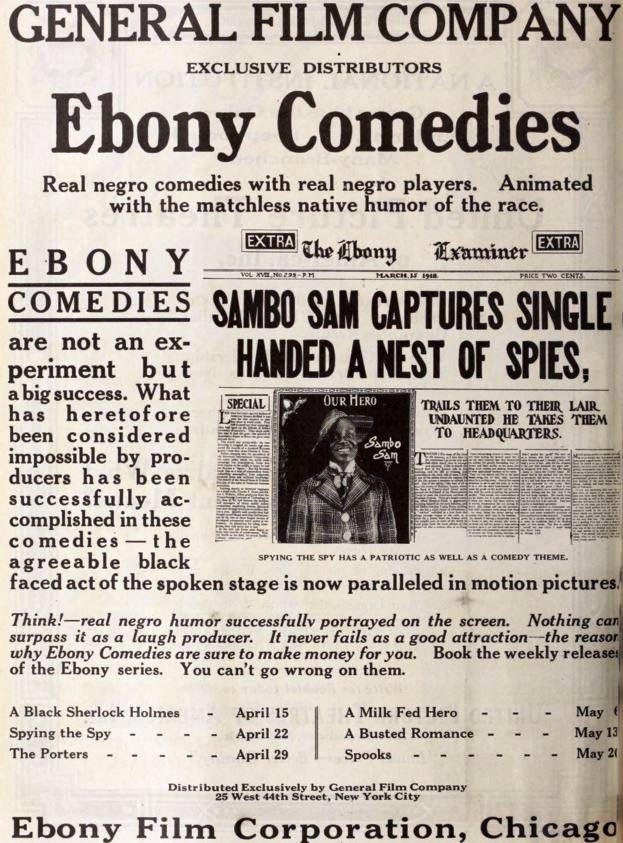

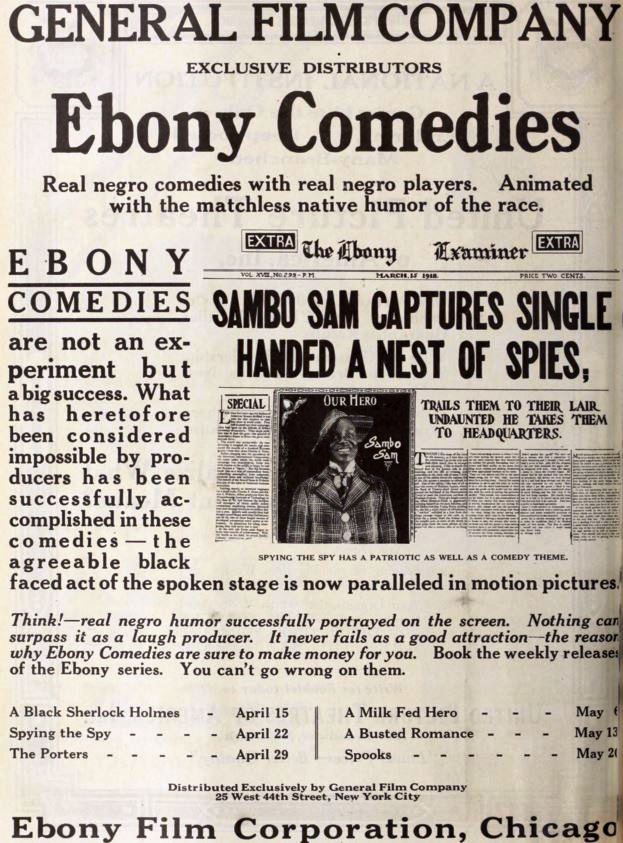

The first film company devoted to the production of race movies was the Chicago-based Ebony Film Company, which began operation in 1915. The first black-owned film company was The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, founded by the famous actor Noble Johnson in 1916. However, the biggest name in race movies was and remains Oscar Micheaux, an Illinois-born director who started The Micheaux Book & Film Company in 1919 and went on to direct at least forty films with predominantly black casts for black audiences. Also in 1919, seeing how lucrative the growing race movie market was, Jacksonville, Florida’s Norman Film Manufacturing Company switched tracks and began making race films, starting with an all black remake of one of their earlier films.

Norman Studios was an American film studio in Jacksonville, FL. Founded by Richard Edward Norman, the studio produced silent films featuring all-African-American casts from 1920 to 1928. The only surviving studio from the period of early filmmaking in Jacksonville, its facilities are now the Norman Studios Silent Film Museum.

One of the most prominent studios creating films for black audiences in the silent era, Norman’s films featured all-black casts with protagonists in positive roles. During its run it produced eight feature length films and numerous shorts; its only surviving film, The Flying Ace, has been restored by the Library of Congress. The studio transitioned to distribution and promotion after the rise of talking pictures made its technology obsolete, and eventually closed. In the 21st century, the studio’s facilities were restored and re-purposed as a museum.

On October 31, 2016, the location was designated a National Historic Landmark.

Born in Middleburg, Florida in 1891, Richard Edward Norman started his career in the Midwest by making movies for white audiences in the 1910s. His early work was a series of “home talent” films, in which he would travel to various towns with stock footage and a basic script; after recruiting local celebrities for minor roles. Norman moved to Jacksonville during the height of the film industry and bought the studio in 1920 at the age of 29.

During the time, films with an African-American cast and shown specifically to African-American audiences were known as race films. Norman Studios produced several of these films during the 1920s seeing how lucrative the market was for black audiences.

The only film from Norman Studios to be restored and kept in the Library of Congress, The Flying Ace was dubbed “the greatest airplane thriller ever filmed.” It was filmed entirely on the ground, but used camera tricks to imply movement and altitude for the stationary airplanes. The film was inspired by aviators like Bessie Coleman who sent a letter to Norman Studios expressing a wish to create a film based on her life.

The plot of the film revolves around a former World War I fighter pilot returning home to his previous job of a railroad company detective. Once back, he has to solve a case involving stolen money and a missing employee in order to catch the thieves. The film is the only one from the period known to have survived. The Library of Congress keeps a copy of the film as it is deemed culturally significant. Nowadays, The Flying Ace is screened occasionally across the nation.

This film is notable for several reasons, including the prop plane Norman created, the creative use of the camera to create the thrilling upside down sequences, and the fact that at the time this film was created, African Americans were not allowed to serve as pilots in the United States armed forces.

Other Race Film studios

In the 1920s, more film companies sprang up to exploit the black film audience. Royal Gardens Film Company of Chicago made only one race film. In 1922, Blackburn Velde Productions also made just one film, a vehicle for boxer/actor Jack Johnson. In Kansas City, Missouri there were several black-owned film companies: The Andlauer Film Company, Progress Picture Producing Association, Gate City Feature Films and Turpin Films. In 1926, the Colored Players Film Corporation was founded by white producer David Starkman.

The Original Lafayette Players was the first major professional black drama company in the country, founded back in 1915, but they didn’t get into film until 1928. From 1929 to 1930, Monte Brice Productions existed as a vehicle for the black duo Buck & Bubbles. In 1929, The Christie Film Country began making all-black talkies. In 1929, Fox made Hearts in Dixie.

In the ’30s and ’40s, Hollywood would increasingly make films with all black casts. With their much larger budgets, Hollywood cinema in the studio era largely appropriated race films’ audience and by World War II, an independent black cinema was no more. It wasn’t until the 1960s and ’70s that a new generation of black filmmakers emerged, creating what came to be known as blaxploitation. However, just as Hollywood co-opted race movies, so too was blaxploitation co-opted. Over the following decades, a black independent film movement slowly resurfaced in the ’80s and continues to grow.