GOOD MORNING P.O.U.!

As you get your Sunday breakfast/brunch on, enjoy the sounds of Out To Lunch! by Eric Dolphy’s.

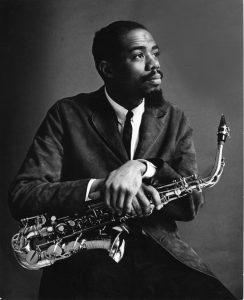

Eric Allan Dolphy, Jr. (June 20, 1928 – June 29, 1964) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and bass clarinetist. On a few occasions, he also played the clarinet and piccolo. Dolphy was one of several multi-instrumentalists to gain prominence in the 1960s. He was one of the first important bass clarinet soloists in jazz, extended the vocabulary and boundaries of the alto saxophone, and was among the earliest significant jazz flute soloists.

His improvisational style was characterized by the use of wide intervals, in addition to using an array of extended techniques to emulate the sounds of human voices and animals. Although Dolphy’s work is sometimes classified as free jazz, his compositions and solos were often rooted in conventional (if highly abstracted) tonal bebop harmony and melodic lines that suggest the influences of modern classical composers Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky.

Early life

Dolphy was born in Los Angeles to Eric Allan Dolphy, Sr. and Sadie Dolphy, who immigrated to the United States from Panama. He picked up the clarinet at the age of six, and in less than a month was playing in the school’s orchestra. He also learned the oboe in junior high school, though he never recorded on the instrument. Hearing Fats Waller, Duke Ellington and Coleman Hawkins led him toward jazz, and he picked up the saxophone and flute while in high school. His father built a studio for Eric in their backyard, and Eric often had friends come by to jam; recordings with Clifford Brown from this studio document this early time.

He performed locally for several years, most notably as a member of bebop big bands led by Gerald Wilson and Roy Porter. He was educated at Los Angeles City College and also directed its orchestra. On early recordings, he occasionally played baritone saxophone, as well as alto saxophone, flute and soprano clarinet.

Dolphy finally had his big break as a member of Chico Hamilton’s quintet. With the group he became known to a wider audience and was able to tour extensively through 1958-1959, when he parted ways with Hamilton and moved to New York City. Dolphy appears with Hamilton’s band in the film Jazz on a Summer’s Day playing flute during the Newport Jazz Festival ’58.

Partnerships

Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus had known Eric from growing up in Los Angeles, and Dolphy joined his band shortly after arriving in New York. He took part in Mingus’ big band recording Pre-Bird, and is featured on “Bemoanable Lady”. Later he joined Mingus’ working band which also included Dannie Richmond and Ted Curson. They worked at the Showplace during 1960 and recorded two early albums together, Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and Mingus at Antibes (the latter adding Booker Ervin on all tracks except “What Love?” and Bud Powell for “I’ll Remember April”). Dolphy, Mingus said, “was a complete musician. He could fit anywhere. He was a fine lead alto in a big band. He could make it in a classical group. And, of course, he was entirely his own man when he soloed…. He had mastered jazz. And he had mastered all the instruments he played. In fact, he knew more than was supposed to be possible to do on them” (Last Date liner notes; Limelight).

During this time, Dolphy also recorded a large ensemble session for the Candid label and took part in the Newport Rebels session. Dolphy left Mingus’ band in 1961 and went to Europe for a few months, where he recorded in Scandinavia and Berlin, though he would record with Mingus throughout his career. He participated in the big band session for Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus in 1963 and is featured on “Hora Decubitus”.

In early 1964, he joined Mingus’ working band again, along with Jaki Byard, Johnny Coles, and Clifford Jordan. This sextet worked at the Five Spot before playing shows at Cornell University and Town Hall in New York and subsequently touring Europe. Many recordings were made of their tour, which, although short, is well-documented.

John Coltrane

Dolphy and John Coltrane knew each other long before they formally played together, having met when Coltrane was in Los Angeles with Miles Davis. They would often exchange ideas and learn from each other, and eventually, after many nights sitting in with Coltrane’s band, Dolphy was asked to become a full member. Coltrane had gained an audience and critical notice with Miles Davis’s quintet, but alienated some jazz critics when he began to move away from hard bop. Although Coltrane’s quintets with Dolphy (including the Village Vanguard and Africa/Brass sessions) are now well regarded, they originally provoked Down Beat magazine to brand Coltrane and Dolphy’s music as ‘anti-jazz’. Coltrane later said of this criticism: “they made it appear that we didn’t even know the first thing about music (…) it hurt me to see [Dolphy] get hurt in this thing.”[1]

The initial release of Coltrane’s stay at the Vanguard selected three tracks, only one of which featured Dolphy. After being issued haphazardly over the next 30 years, a comprehensive box set featuring all of the recorded music from the Vanguard was released by Impulse! in 1997, called The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings. The set features Dolphy heavily on both alto saxophone and bass clarinet, with Eric the featured soloist on their renditions of “Naima”. A later Pablo box set from Coltrane’s European tours of the early 1960s collected more recordings which feature tunes not played at the Village Vanguard, such as “My Favorite Things”, which Dolphy performs on flute.

Booker Little

Before trumpeter Booker Little’s untimely death at the age of 23, he and Dolphy had a very fruitful musical partnership. Booker’s leader date for Candid, Out Front, featured Dolphy mainly on alto, though he played bass clarinet and flute on some ensemble passages. In addition, Dolphy’s album Far Cry recorded for Prestige features Little on five tunes (one of which, “Serene”, was not included on the original album release).

Dolphy and Little also co-led a quintet at the Five Spot during 1961. The rhythm section consisted of Richard Davis, Mal Waldron and Ed Blackwell. One night was documented and has been released on three volumes of At the Five Spot as well as the compilation Here and There. In addition, both Dolphy and Little backed Abbey Lincoln on her album Straight Ahead and played on Max Roach’s Percussion Bitter Sweet.

Others

During this period, Dolphy also played in a number of challenging settings, notably in key recordings by George Russell, Oliver Nelson, and Ornette Coleman. He also worked with Gunther Schuller, multi-instrumentalist Ken McIntyre, and bassist Ron Carter, among many others.

As a leader

Dolphy’s recording career as a leader began with the Prestige label. His association with the label spanned 13 albums recorded from April 1960 to September 1961, though he was not the leader for all of the sessions. Fantasy eventually released a 9-CD box set containing all of Dolphy’s recorded output for Prestige.

Dolphy’s first two albums as leader were Outward Bound and Out There; both featured artwork by Richard “Prophet” Jennings. The first, sounding closer to hard bop than some later releases, was recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey with then newcomer trumpet player Freddie Hubbard. The album features three Dolphy compositions: “G.W.”, dedicated to Gerald Wilson, and the blues “Les” and “245”. Out There is closer to third stream music which would also form part of Dolphy’s legacy, and features Ron Carter on cello. Charles Mingus’ “Eclipse” from this album is one of the rare instances where Dolphy solos on soprano clarinet (others being “Warm Canto” from Mal Waldron’s The Quest, “Densities” from the compilation Vintage Dolphy, and “Song For The Ram’s Horn” from an unreleased recording from a 1962 Town Hall concert).

Dolphy recorded several unaccompanied cuts on saxophone, which at the time had been done only by Coleman Hawkins and Sonny Rollins, making Dolphy the first to do so on alto. The album Far Cry contains his famous performance of the Gross-Lawrence standard “Tenderly” on alto saxophone, and his subsequent tour of Europe quickly set high standards for solo performance with his exhilarating bass clarinet renditions of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child” (the earliest known version was recorded at the Five Spot during his residency with Booker Little). Numerous recordings were made of live performances by Dolphy on this tour, in Copenhagen, Uppsala and other cities, and these have been issued by many record labels, drifting in and out of print, though many if not all have been remastered and are readily available. He also recorded two takes of a short solo rendition of “Love Me” in 1963, released on Conversations and Muses.

Twentieth century classical music also played a significant role in Dolphy’s musical career. He performed Edgard Varèse’s Density 21.5 for solo flute at the Ojai Music Festival in 1962[2]and participated in Gunther Schuller’s and John Lewis’ Third Stream efforts of the 1960s.

Around 1962–63, one of Dolphy’s working bands included the young pianist Herbie Hancock, who can be heard on The Illinois Concert and Gaslight 1962 and the unissued Town Hall concert with poet Ree Dragonette.

In July 1963, Dolphy and producer Alan Douglas arranged recording sessions for which his sidemen were among the leading emerging musicians of the day, and the results produced the albums Iron Man and Conversations, as well as the Muses album released in Japan in late 2013. These sessions marked the first time Dolphy played with Bobby Hutcherson, whom he knew from Los Angeles. The sessions are perhaps most famous for the three duets Dolphy performs with Richard Davis on “Alone Together”, “Ode To Charlie Parker”, and “Come Sunday”; the aforementioned release Muses adds another take of “Alone Together” and an original composition for duet from which the album takes its name.

In 1964, Dolphy signed with Blue Note Records and recorded Out to Lunch! with Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, Richard Davis and Tony Williams. This album features Dolphy’s fully developed avant-garde yet highly structured compositional style rooted in tradition. It is often considered his magnum opus.[3]

Final months

After Out to Lunch! and an appearance on Andrew Hill’s classic Point of Departure, Dolphy left for Europe with Charles Mingus’ sextet in early 1964. Before a concert in Oslo, he informed Mingus that he planned to stay in Europe after their tour was finished, partly because he had become disillusioned with the United States’ reception to musicians who were trying something new. Mingus then named the blues they had been performing “So Long Eric”. Dolphy intended to settle in Europe with his fiancée, Joyce Mordecai, who was working in the ballet scene in Paris. After leaving Mingus, he performed and recorded a few sides with various European bands, and American musicians living in Paris, such as Donald Byrd and Nathan Davis. The famous Last Date with Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink was recorded in Hilversum, the Netherlands, though it was not actually Dolphy’s last concert. Dolphy was also preparing to join Albert Ayler for a recording and spoke of his strong desire to play with Cecil Taylor. He also planned to form a band with Woody Shaw and Billy Higgins, and was writing a string quartet entitled “Love Suite”.

Eric Dolphy died accidentally in Berlin on June 29, 1964. Some details of his death are still disputed, but it is accepted that he died of a coma brought on by an undiagnosed diabetic condition. The liner notes to the Complete Prestige Recordings box set say that Dolphy “collapsed in his hotel room in Berlin and when brought to the hospital he was diagnosed as being in a diabetic coma. After being administered a shot of insulin he lapsed into insulin shock and died.” A later documentary and liner note dispute this, saying Dolphy collapsed on stage in Berlin and was brought to a hospital. The attending hospital physicians had no idea that Dolphy was a diabetic and decided on a stereotypical view of jazz musicians related to substance abuse, that he had overdosed on drugs. He was left in a hospital bed for the drugs to run their course.[4]

Ted Curson remembers, “That really broke me up. When Eric got sick on that date [in Berlin], and him being black and a jazz musician, they thought he was a junkie. Eric didn’t use any drugs. He was a diabetic – all they had to do was take a blood test and they would have found that out. So he died for nothing. They gave him some detox stuff and he died, and nobody ever went into that club in Berlin again. That was the end of that club.”[5]

Charles Mingus said, “Usually, when a man dies, you remember—or you say you remember—only the good things about him. With Eric, that’s all you could remember. I don’t remember any drags he did to anybody. The man was absolutely without a need to hurt”.[6]

Dolphy was posthumously inducted into the Down Beat magazine Hall of Fame in 1964. John Coltrane paid tribute to Dolphy in an interview: “Whatever I’d say would be an understatement. I can only say my life was made much better by knowing him. He was one of the greatest people I’ve ever known, as a man, a friend, and a musician.”[7] Dolphy’s mother, Sadie, who had fond memories of her son practicing in the studio in the backyard of their house, gave instruments that Dolphy had bought in France but never played to Coltrane,[8][page needed] who subsequently played the flute and bass clarinet on several albums before his own death in 1967.

Dolphy was engaged to be married to Joyce Mordecai, a classically trained dancer. Before he left for Europe in 1964, Dolphy left papers and other effects with his friends Hale and Juanita Smith. Eventually much of this material was passed on to the musician James Newton. It was announced in May 2014 that five boxes of music papers had been donated to the Library of Congress.[9]

Influence

Dolphy’s musical presence was influential to many young jazz musicians who would later become prominent. Dolphy worked intermittently with Ron Carter and Freddie Hubbard throughout his career, and in later years he hired Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson and Woody Shaw to work in his live and studio bands. Out to Lunch! featured yet another young performer, drummer Tony Williams, and Dolphy’s participation on the Point of Departure session brought his influence into contact with up and coming tenor man Joe Henderson.

Carter, Hancock and Williams would go on to become one of the quintessential rhythm sections of the decade, both together on their own albums and as the backbone of Miles Davis’s second great quintet. This aspect of the second great quintet is an ironic footnote for Davis, who was not fond of Dolphy’s music: in a 1964 Down Beat “Blindfold Test”, Miles famously quipped, “The next time I see [Dolphy] I’m going to step on his foot.”[10] However, Davis absorbed a rhythm section who had all worked under Dolphy, thus creating a band whose brand of “out” was very similar to Dolphy’s.

Dolphy’s virtuoso instrumental abilities and unique style of jazz, deeply emotional and free but strongly rooted in tradition and structured composition, heavily influenced such musicians as Anthony Braxton, members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Oliver Lake, Julius Hemphill, Arthur Blythe, Aki Takase, Rudi Mahall, Don Byron and many others. Dolphy’s compositions are the inspiration for many tribute albums, such as Oliver Lake’s Prophet and Dedicated to Dolphy, Jerome Harris’ Hidden In Plain View, Otomo Yoshihide’s re-imagining of Out to Lunch!, Silke Eberhard’s Potsa Lotsa: The Complete Works of Eric Dolphy, and Aki Takase and Rudi Mahall’s duo album Duet For Eric Dolphy.

In addition, his work with jazz and rock producer Alan Douglas allowed Dolphy’s style to posthumously spread to musicians in the jazz fusion and rock environments, most notably with artists John McLaughlin and Jimi Hendrix. Frank Zappa, who drew his inspiration from a variety of musical styles and idioms, paid tribute to Dolphy in the instrumental “The Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue” (on the 1970 album Weasels Ripped My Flesh) and listed Dolphy as an influence on the liner notes for the Mothers’ first LP, Freak Out!.

In 1997 Vienna Art Orchestra released Powerful Ways: Nine Immortal Non-evergreens for Eric Dolphy, as part of their 20th anniversary boxset.

In 2014, marking 50 years since Dolphy’s death, Berlin-based pianists Alexander von Schlippenbach and Aki Takase led a project titled “So Long, Eric!”, celebrating Dolphy’s music and featuring musicians such as Han Bennink, Karl Berger, Rudi Mahall, Axel Dörner and Tobias Delius.

(SOURCE: Wikipedia)