![]()

I admit that I had never heard of the National Negro Congress (yesterday’s topic) or its youth affiliate organization, The Southern Negro Youth Congress. HIStory would have you believe black people didn’t organize anything until the day after Rosa Parks sat down on the bus. However, we’ve had organized protests and strives for equal rights since the day of emanicipation. More of these stories need to be studied by our youth.

Members of the Southern Negro Youth Congress Meet with Idaho Senator Glen Taylor

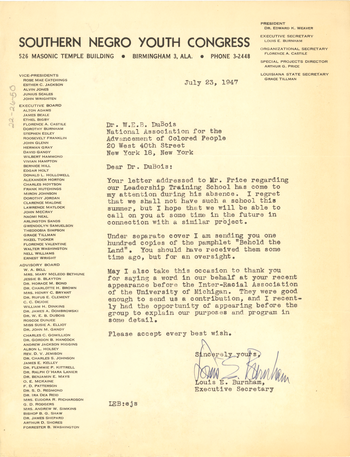

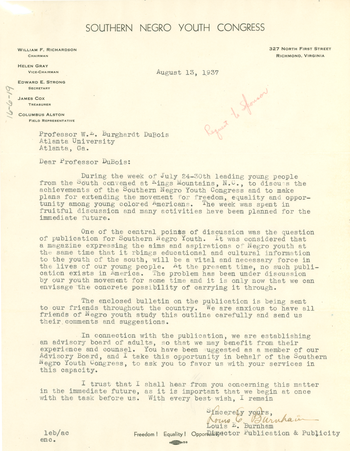

The Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) was formed in 1937 by young people who had attended the National Negro Congress (NNC) in Chicago, Illinois in 1936 and wanted to implement its call for action. These young leaders, including activists James Jackson, Helen Gray, Esther Cooper, and Edward Strong, gathered in Richmond, Virginia in 1937 and formed the SNYC. They initially established their headquarters in Richmond before moving it to Birmingham, Alabama in 1939. SNYC had the support of prominent black adult leaders including Mary McCloud Bethune, Paul Robeson, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, A. Philip Randolph, and W.E.B. DuBois.

The first SNYC conference was held in Richmond, Virginia on February 13 and 14, 1937 at the Fifth Baptist Church. Five hundred thirty-four delegates from across the South attended the meeting including individuals from almost every historically black college as well as delegates representing YMCA branches and chapters of the Girl and Boy Scouts across the region. One international delegate, a young woman from China, also attended. Like its parent organization, the National Negro Congress, SNYC was affiliated with the Communist Party USA and also included Communists among its members.

Officers were elected to one year terms while the adult advisory board raised funds and offered advice. The first successful SNYC campaign helped black tobacco workers organize a union in Richmond. Next it organized anti-lynching campaigns across the South.

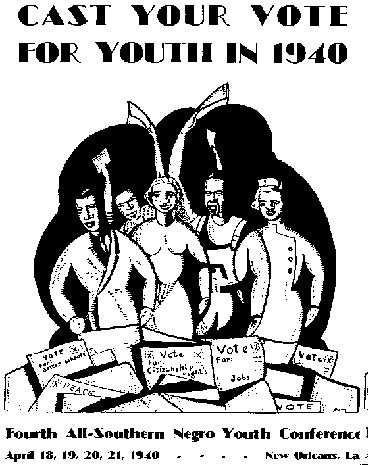

Over the next twelve years SNYC formed chapters in ten southern states with a total membership of 11,000 at its peak. Over those years the organization encouraged southern blacks to join the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), helped register voters, and on one occasion visited the White House to enlist Eleanor Roosevelt’s support for their efforts. During World War II they testified before the Fair Employment Practices Committee describing employment discrimination in the South. SNYC members also sponsored the Caravan Puppeteers, a political puppet show, to explain how rural blacks could secure the right to vote. Their newsletter, Cavalcade, awarded prizes to college students for art and poetic interpretation of Howard Fast’s 1944 novel, Freedom Road.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress performed such studies as taking items being purchased in a black community and then comparing the prices to those same items being purchased in a white community. This study showed that prices for the same goods were 20-30% higher in the black communities then they were in the white communities, which meant that the citizens who were struggling most to survive were actually paying higher prices for the items that were necessary for them to live.

The organization made extraordinary progress in making rural southern black people aware of their rights and in teaching strategies for protest. Their activities also gained the attention of opponents ranging from Eugene “Bull” Connor, the Chief of Birmingham’s Department of Public Safety, to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Since the inception of the Southern Negro Youth Congress in 1937 the concepts of communism and social justice for African-Americans had always been present as those who viewed from the outside feared these ideologies and for the Southern Negro Youth Congress, these would last for the 12 years of its existence. With the emergence of the American Communist Party and their visibility from 1935 to 1939 the United States government feared the communist threat instilling the American people and causing problems.

The presence of some communist members and the activities done by SYNC made the FBI was suspicious. From 1940 to 1952 the FBI gathered data on the Southern Negro Youth Congress through the installation of technical surveillance such as telephone and microphone taps. Besides this the FBI paid informants and paid for subscriptions to the Southern Negro Youth Congress’ publications. However, the imminent perception of the Southern Negro Youth Congress as a Communist Party dominated the mass, which subsequently led to the downfall of many Southern Negro Youth Congress campaigns and its popularity.

The Southern Negro Youth Conference in 1948 held their eighth Southern Negro Youth Congress Conference that also happened to be the last conference. The meeting was held on April 23, 24, and 25, 1948 in Birmingham, AL, where the headquarters was located. The eighth conference attracted national news headlines as well as showed the extent of control over the lives of citizens that lived in the South. During this time the Police Commissioner was Bull Connor who used everything in his power to prevent the Southern Negro Youth Congress from gathering stating that the separation of races was required and that any action that disobeyed this law was to be reinforced by the police.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress looked for churches to hold the meetings but upon securing a location to use Bull Connor would often intervene and call the Minister of the church facilities being used and state that since the Southern Negro Youth Congress was an interracial organization that the meeting would violate the state of Alabama’s laws. Three black churches turned down the Southern Negro Youth Congress before Reverend H. Douglas Oliver allowed the meeting to be held in his pastor of the Alliance Gospel Tabernacle. The meeting was held on May 1, 1948 and upon arrival all white members were arrested and charged for breaking the segregation laws. Despite this occurrence the meeting still commenced with the remaining black members under the segregated conditions. At the meeting the Southern Negro Youth Congress passed resolutions condemning the segregation laws and denying any affiliation with the Communist Party. The contentions of the party were not accepted by the U.S. Department of Justice and shortly after the meeting Edward K. Weaver; president of the Southern Negro Youth Congress was forced to resign.

Paul Robeson at the cultural festival of the Southern Negro Youth Congress held at Tuskegee Institute in 1942

With the end of the eighth Southern Negro Youth Congress and the resigning of the president the Congress began to lose rapid popularity in the south and north as membership declined drastically. The opposing powers against the Congress were too much to withstand as well as the times that occurred post World War II. The United States was undergoing what later became known as the Cold War and this led to heightened racial tension and encouraged local and national law enforcement agencies to increase the surveillance of radical and subversive organization. According to the United States Attorney General, Tom Clark, the Southern Negro Youth Congress appeared as a subversive organization.

Despite numerous acts of intimidation by local and federal authorities as well as groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, SNYC inspired a generation of African Americans, including Sallye Bell Davis (the mother of Angela Davis) and Julian Bond, Sr., to become political activists. In doing so, the Southern Negro Youth Congress laid the ground work for the civil rights movement of the 1950s.

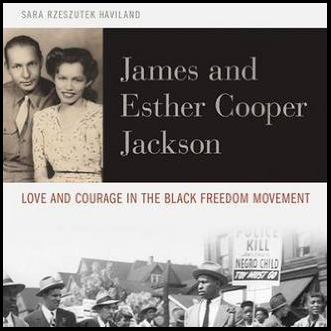

Read more about 2 of the founders of SYNC, James Jackson and Esther Cooper Jackson.