Good Morning POU!

Christmas was a popular time of year to run away to seek freedom in the Northern states. Slaves reasoned that they were less likely to be missed or apprehended on the roads at Christmas time than at any other time of the year, since they would not be expected to show up for work until after the holiday. Furthermore, whites were accustomed to seeing many black people on the streets during the holiday season. The time off that was allotted to slaves during the holidays may have inspired a number of slave revolts, as approximately one third of both documented and rumored slave rebellions reportedly occurred around Christmas. In 1856, slave revolts occurred in nearly every slaveholding state at Christmas time.

Slaves took advantage of relaxed work schedules and the holiday travels of slaveholders, who were too far away to stop them. While some slaveholders presumably treated the holiday as any other workday, numerous authors record a variety of holiday traditions, including the suspension of work for celebration and family visits.

Because many slaves had spouses, children, and family who were owned by different masters and who lived on other properties, slaves often requested passes to travel and visit family during this time. Some slaves used the passes to explain their presence on the road and delay the discovery of their escape through their masters’ expectation that they would soon return from their “family visit.”

The Rev. J. W. Loguen, as a Slave and as a Freeman.

A Narrative of Real Life:

Jermain Loguen plotted a Christmas escape, stockpiling supplies and waiting for travel passes, knowing the cover of the holidays was essential for success: “Lord speed the day!–freedom begins with the holidays!”. These plans turned out to be wise, as Loguen and his companions are almost caught crossing a river into Ohio, but were left alone because the white men thought they were free men “who have been to Kentucky to spend the Holidays with their friends”. He went on to become an agent of the Underground Railroad.

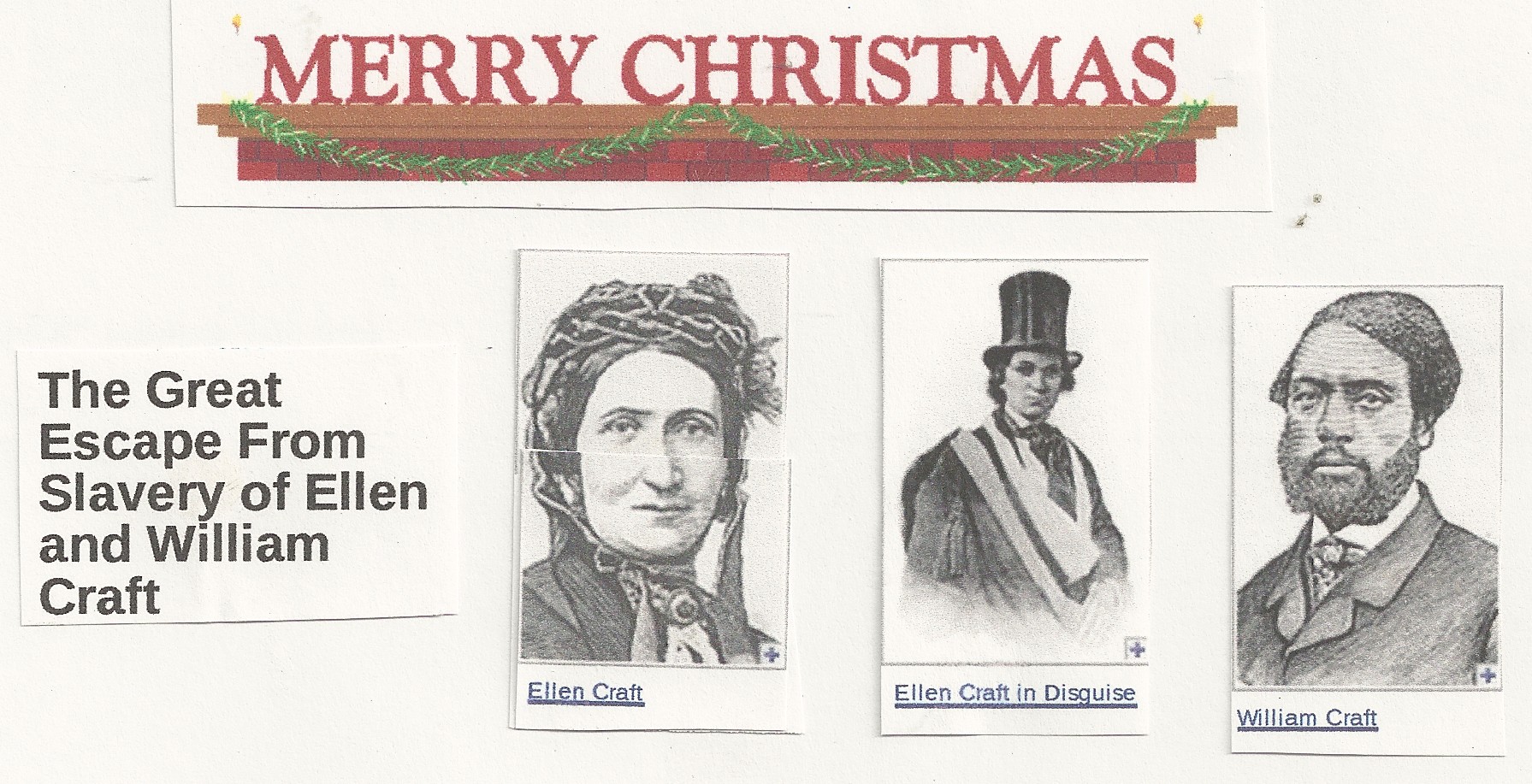

Likewise, William and Ellen Crafts escaped together at Christmastime. They took advantage of passes that were clearly meant for temporary use. Ellen “obtained a pass from her mistress, allowing her to be away for a few days:

The cabinet-maker with whom I worked gave me a similar paper, but said that he needed my services very much, and wished me to return as soon as the time granted was up. I thanked him kindly; but somehow I have not been able to make it convenient to return yet; and, as the free air of good old England agrees so well with my wife and our dear little ones, as well as with myself, it is not at all likely we shall return at present to the ‘peculiar institution’ of chains and stripes” (pp. 303-304).

William was born in Macon, Georgia to a master who sold off Craft’s family to pay gambling debts. William’s new owner, a local bank cashier, apprenticed him as a carpenter in order to earn money from William’s labor. Ellen Craft was born in Clinton, Georgia and was the daughter of an African American biracial slave and her white owner. Because of her light complexion, strangers often mistook Ellen as white. Bothered by such a situation, Ellen’s plantation mistress sent the 11-year-old Ellen to Macon to the mistress’s daughter as a wedding present in 1837, where Ellen served as a ladies maid.

It was in Macon that William and Ellen met. In 1846 their owners allowed Ellen and William to marry, but they could not live together since they had different owners. Obviously unhappy with that enforced separation and the fear that their masters could sell any children, the couple started to save money some of the meager wages they were allowed to keep and planned an escape.

In December 1848, they did just that. Because they were “good” slaves, their masters permitted them passes for a few days leave at Christmastime. Those days would give the couple time to be missing without notice. They decided that they would escape by traveling as a white male and his black servant (it was not customary for women to travel with male servants).

On December 21, 1848, William cut Ellen’s hair and put her right arm in a sling. Not being able to read or write, but knowing others would ask “Ellen” the “free male” to sign papers at check points along their way, an injured arm allowed no signatures. Also William partially covered Ellen’s face with a “bandage” to further hide her female appearance. Ellen dressed in trousers she’s sewn and a top hat.

They went by train from Macon to Savannah; a steamship to Charleston, South Carolina; another steamer to Wilmington, North Carolina; a train to Fredericksburg, Virginia; another steamer to Washington, D.C; a train to Baltimore, Maryland, and thence to Pennsylvania. They had to travel separately the whole journey which was filled with fear and the constant and real worry that they would be caught. Their fear were almost realized several times, but they nonetheless arrived in Philadelphia on Christmas day, 1848. The Crafts moved on to Boston, which had an established free black community and a well-organized, protective abolitionist activity. William, a skilled cabinetmaker, started a furniture business.