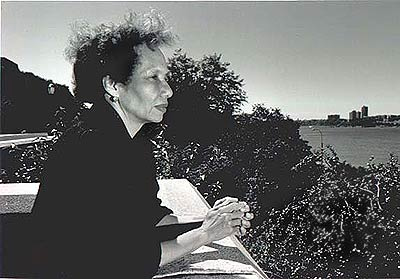

Throughout her writing career, Adrienne Kennedy has used her own life experiences as symbolic of the divisiveness of American race relations. Like Kennedy, the characters in her plays are often light-skinned black women torn between their blackness and whiteness.

Adrienne Hawkins was born in 1930 to Georgia-born parents who instilled in her a pride in black accomplishment. Her father, Cornell W. Hawkins, attended Morehouse College and served as executive director of the Cedar Branch of the Cleveland YMCA and on the City’s race relations staff. Her mother, Etta Hawkins, was a graduate of Atlanta University and a teacher.

Her parents and their friends—teachers, social and civic workers, doctors and lawyers—were members of the NAACP and the Urban League, she notes in her 1987 memoir, People Who Led to My Plays. But Kennedy was aware from an early age that she also had white relatives whose ancestors had come from England, and she created alter egos who sought artistic and cultural fathers among the likes of Shakespeare, Chaucer and William the Conqueror.

Raised in the then interracial, middle-class Cleveland neighborhoods of Mt. Pleasant and Glenville, Kennedy found herself confronting prejudice for the first time at Ohio State University. “The immensity, the dark, rainy winters, the often open racial hatred of the girls in the dorm continued to demoralize me,” she would later write. She left college a person who “had lost my equilibrium” and spent the next decade struggling to find her own voice. Influences as diverse as Federico Garcia Lorca’s symbolic plays, the cadences of the psalms, the poetry of jazz, French surrealist movies, Picasso’s Guernica, Jackson Pollock’s abstract paintings, and African masks liberated her from the confines of realism and paved the way for her distinctive lyrical, non-linear and dreamlike style.

It was on “a miraculous trip” to West Africa that Kennedy “discovered a strength in being a black person.” Returning to live in New York, she joined Edward Albee’s Playwrighting Workshop. Encouraged by Albee to let her “guts out on stage,” she wrote her first play, Funnyhouse of a Negro (1964), which won an Obie. The decade that followed unleashed a torrent of dense surrealist plays that found a place in experimental theaters such as La Mama and the Open Theater, as well as the Public Theater of the New York Shakespeare Festival.

But Kennedy soon found herself in a kind of no man’s land as a black writer. As Billie Allen, who created the role of “Negro Sarah” in Funnyhouse, later noted, some black audiences were offended by Kennedy’s portrayal of black “secrets” on stage. “Hair, for example, had not been dealt with in the theater.” Her unabashed, though ambivalent love of things English and Hollywood presented difficulties for other critics.

Except for Joseph Chaikin’s 1976 production of her play A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White, the ’70s saw no new work by Kennedy, who spent most of the decade as a visiting professor at several distinguished universities. But in the ’80s a new flurry of writing yielded Deadly Triplets: A Theatre Mystery and Journal (1990), her memoir and a cluster of new plays involving a character named Susan Alexander. One of these, Ohio State Murders, was commissioned by the Cleveland-based Great Lakes Theater Festival, of which Gerald Freedman was then producing director.

Alexander, a successful African-American writer (played in the 1992 Great Lakes production by Ruby Dee), has been asked to return to her alma mater to discuss the sources of violent imagery in her works. Spiraling back in a dreamlike journey through time, she relives the unspeakable prejudices that violated her student years in the early 1950s. As the literal murders of the play’s title are disclosed in the form of a mystery story, the spiritual murders that feed the secret wellspring of Alexander’s pain are also uncovered.